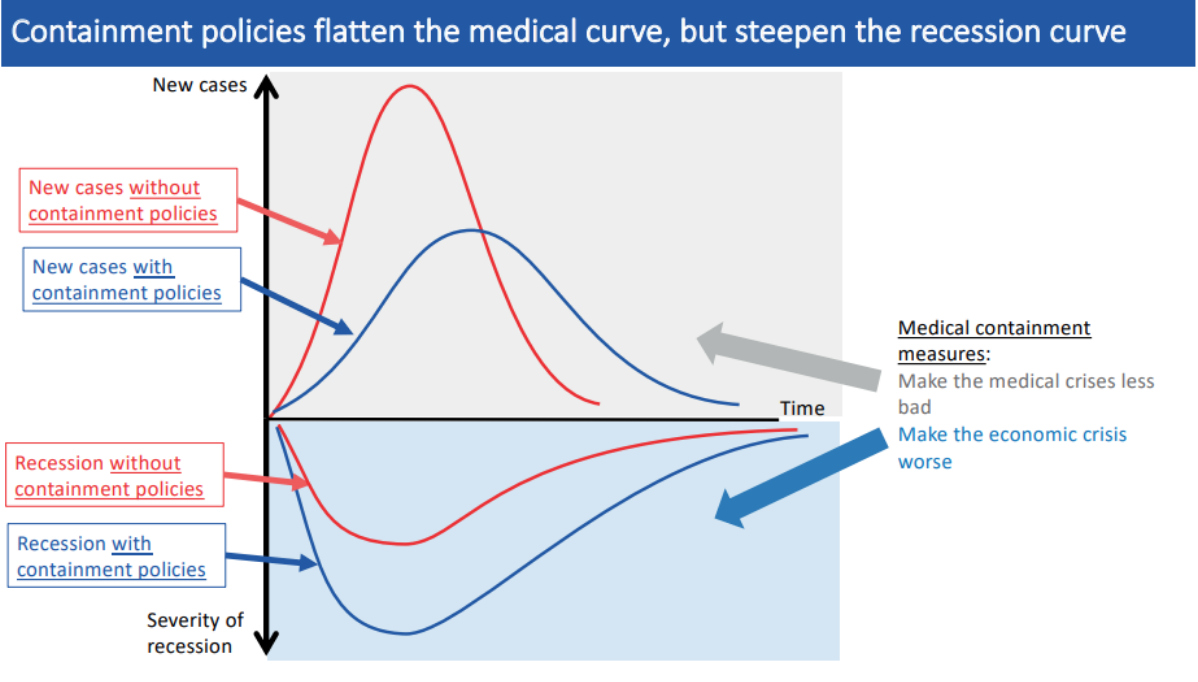

Governments around the world have to contend with saving lives or livelihoods. Should they enact tough lockdowns, at the expense of the economy, to flatten the curve and save lives? Figure 1 shows how containment policies have a dual effect: the increase in lockdowns might also result in a more severe recession. Nevertheless, it is not a zero-sum game, for these policy tradeoffs are neither simple nor dichotomous.

Figure 1. Containment policies and their effects on epidemiological and recession curves

(Source: Baldwin and Weber di Mauro, 2020)

To keep the economy afloat amid the pandemic, there has been a remarkable global shift towards re-centering the state and rolling out stimulus packages. The US is putting together one of its largest emergency aid packages, offering over US$2 trillion in bailouts, income supports, and hospital funding, and the UK has released its fourth emergency package to support its economy.

Across ASEAN, governments have been releasing substantive stimulus packages as well (see Table 1). Many emerging economies are struggling to craft generous relief plans, having to manage a series of pre-existing issues such as foreign debt and currency volatility. Singapore’s package as a percentage of GDP is one of the largest due to the country’s vast reserves, with more financial support anticipated.

Table 1

COVID-19 Stimulus Packages across ASEAN*

(updated as of 4 April 2020; compiled by author from national news sources)

| Country | Package in USD (% GDP) | Key Provisions |

| Brunei | 313 million(1.4% GDP) | Deferment of principal or loan repayments; employees trust fund and pension support |

| Cambodia | 800 million to 2 billion (3.6% to 9.0%)** | Factory worker wages and tourist sector tax breaks |

| Indonesia | 9.6 billion (1% GDP) | Two packages: worker tax incentives and subsidies; individual and corporate tax breaks |

| Laos | 11 million(0.07% GDP) | Ongoing discussions for a 13-part package to minimize the economic impact of the virus |

| Malaysia | 58 billion (16% GDP) | Utility discounts, one-off cash handout, and microcredit for SMEs |

| Myanmar | 72 million (0.1% GDP) | Loans, eased tax deadlines, and tax exemptions for eligible businesses |

| Philippines | 3.93 billion (1.3% GDP) | Social protection for poor families, health workers, and targeted wage subsidies |

| Singapore | 38.5 billion (11% GDP) | Extending the jobs support scheme, co-funding local wages for impacted industries, and providing a self-employed relief fund |

| Thailand | 12.7 billion(2.8% GDP)*** | Soft loans, relaxed debt repayments, and reduced interest rates for businesses |

| Vietnam | 3.76 billion(1.7% GDP) | Payouts to near-poor households and vulnerable groups; tax break, delayed tax payments, reduction in land lease fee |

*) These stimulus packages are not comprehensive and are subject to rapidly changing dynamics, and one should also consider the relevant non-fiscal shielding measures that are being implemented.

**) The size of Cambodia’s stimulus package depends on the length of the outbreak: the lower amount for six months, and the higher amount if it lasts over a year.

***) An additional package is being discussed, which would bring the total amount to over 1 trillion Thai Baht (6.8% GDP).

The supply and demand shock from this pandemic are affecting corporations, businesses, and the everyday citizen in different ways. Many do not have the luxury of staying at home, and those in the gig economy and the precarious informal sector lack adequate labor protections to keep them afloat. As Theophilus Kwek has pointed out, states have an obligation to deliver protections to citizens and ensure that the vulnerable are also supported. But there are gaps in provisions, and these need to be explored. One of these gaps includes a new form of vulnerability being experienced by small business owners in Singapore, many of whom are in the food and beverage (F&B) and retail industries.

Singapore’s Stimulus Package

Singapore’s government has identified three major areas of its economy that are affected and has targeted measures in the Resilience Budget accordingly. First, its aviation and tourism sectors are seeing a severe drop in demand due to travel restrictions. According to PM Lee’s interview with Fareed Zakaria, “aviation has died.” Both the aviation and tourism sectors will receive a 75% offset for the first S$4,600 of wages for local employees. The former will also receive a host of support measures (e.g. rebates of landing and parking charges, rental relief for airlines, etc.), with Singapore Airlines receiving a S$15 billion bailout from Temasek.

Second, its consumer-facing services and the focus of this article—F&B and retail—are also severely affected. These are tangible problems for many Singaporeans and residents, as these three industries comprise over 500,000 employees, making up 13.3% of the country’s total employment share. Some key provisions include the following: food services will receive a 50% offset for local employees’ wages and other sectors will receive 25% co-funding of wages; eligible government-owned or managed non-residential facilities will receive rental waivers: three months for hawker centers and markets, two months for commercial tenants, and other non-residential tenants may receive a half months’ worth of rental waiver; badly affected commercial properties also receive full property rebates, up from the 15% to 30% announced earlier. Moreover, new legislation is being proposed in Parliament to ensure that property tax rebates are passed to their tenants in full and the provision of relief against contractual obligations amid this outbreak.

Third, manufacturing and wholesale trade have been disrupted due to falling demand and disrupted supply chains. The government is providing a 25% offset in funding for every local worker, helping these industries stay afloat. There are additional measures that have been enacted as well, including the COVID-19 support grant, The Courage Fund, and the Temporary Relief Fund, where qualifying citizens should apply at the relevant Social Service Offices (SSOs).

The state is providing a wide swathe of economic support, but how long can this last? Trade and Industry Minister Chan Chun Sing has stated that these measures will last three to six months and the government is prepared to disburse more packages if necessary, depending on external factors: the state of the global supply chain, potential protectionist measures, and recurring waves of the virus. It is urgent to act, but it is also vital to act correctly, as the economic fallout from bad policies will have long-term effects.

The Temporal Dimensions of COVID-19’s Effects

However tempting it is to take these three to six months as the only temporal parameter, it is important to consider the many dimensions of time to see the bigger picture. Disasters occur at the nexus of various temporal trajectories—businesses face the suddenness of the pandemic-generated economic shocks, inherit a longstanding distribution of inequality, face an uncertain future, and require urgent support.

Billions have been placed under lockdown and life has suddenly transformed. Dense city centers such as London, Los Angeles, São Paulo, Tokyo, and Sydney that were previously teeming with life have now become ghost towns. For many, the anxiety of finding out that someone in close contact had tested positive and the perpetual worry for one’s parents or grandparents, all the while trying to maintain a ‘new normal’ has been a particularly stressful situation, exacerbated by social distancing policies. According to UNESCO, 1.5 billion students around the world have been affected by school closures, implicating increased needs for family provision or alternative care arrangements. Singapore has mitigated this suddenness in its education system through piloting one-day-a week home-based learning before shifting to its full implementation, weighing the suddenness and urgency of the pandemic with strategically timed national announcements.

Simultaneously, COVID-19 struck amidst a long-time running build-up of inequalities and vulnerabilities. In other words, the uneven distribution of its consequences has been a long time coming. Historically, small business owners have been more vulnerable than large companies. The Economist states that “downturns are capitalism’s supporting mechanism,” following that up with a statistic that the past three recessions saw American firm share prices in the top quartile rise by 6% on average, while those at the bottom fell by 44%. The resilience exhibited by large corporations reflects their clear competitive advantage, as they generally have more reliable supply networks, as well as higher margins and cash buffers that enable their increased investments. On the other hand, small businesses have long been plagued by high costs of rent and manpower. As such, smaller, home-grown establishments are poised to face the lion’s share of economic fallout in relation to larger businesses.

Thus, for the small business owner in Singapore, how can they keep their shop or restaurant open amid this crisis? McKinsey estimates a 40%-50% reduction in discretionary spending is expected around the world with some industries taking the brunt of this economic downturn. Tsinghua and Peking Universities recently conducted a survey of 995 Chinese small and medium-sized enterprises and 85% of them responded that they could only survive for no longer than three months. A similar situation faces Singaporean small business owners.

Table 2 shows that F&B and retail industries have a 4%-5% operating surplus as a percentage of their operating receipt. Singapore’s announcement of the ban on dine-in meals from April 7 to May 4, where consumers could either dabao (takeaway) or order food online, significantly reduces F&B sales. This would immediately drop into a significant deficit from the plummeting operating receipt numbers due to lower spending. The government’s 50% co-funding of food service employee wages might only account for 15% of their expenditure, as 30% of business costs go towards remuneration.

Table 2

Key Indicators for F&B and Retail Industries (2018) in millions SGD

Source: SingStat (Key Indicators By Industry Group In All Services Industries)

| F&B | Retail | |

| Operating Receipt | 10,959 | 48,470 |

| Operating Expenditure | 10,829 | 46,486 |

| Operating Surplus | 523 | 2,571 |

| Value Added | 3,778 | 7,480 |

| Surplus as a Percentage of Receipt | 4.8% | 5.3% |

It is uncertain when the government will deem the curve to be “flat enough” and start easing restrictions to allow for increased consumer spending. Without a safety net and the most robust of working capital management models, many small businesses are bound to fail.

To ground this explanation, previous-DJ-and-now-restaurant-owner Daniel Ong explains his situation. His rent for one of three restaurants costs S$25,000, wages S$40,000, and reduced cash flow cannot account for all the lost business from the office workers who are now working from home and no walk-in customers. Again, supposing the government supports 50% of the wages, that will still be S$20,000 for wages on top of the rent that he would have to pay, as his premises are not government-owned. Daniel has been calling for greater flexibility from private landlords to waive rental fees to save his business.

He is not alone. Daniel is one of the 28,000 foodservice outlets across the nation, many of which are independently run stalls (see Table 3). The Singapore Retailers Association has appealed to landlords for flexibility in their rental charges, asking for either half of the base rent or not more than 15% of a tenant’s gross turnover to be paid for six months. The Restaurant Association of Singapore has made a similar announcement asking for rental rebates for its F&B operators. Unless a major change occurs, these economic measures are not adequate to cover the overhead and prevent widespread business closures.

Table 3

Foodservice Outlets in Singapore 2018

Source: Euromonitor Statistics, DBS Bank

| Independent | Chained | Total | |

| Cafes or Bars | 1,740 | 625 | 2,365 |

| Full-service restaurants | 1,266 | 468 | 1,734 |

| Limited-service restaurants | 64 | 1,534 | 1,598 |

| Self-service cafeterias | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Street stalls or kiosks | 20,352 | 2,032 | 22,384 |

| Total | 23,422 | 4,666 | 28,088 |

New Economic Vulnerabilities

It is clear that time and tide waits for no pandemic, and neither do operating expenditures. The pandemic’s suddenness mapped onto existing payment structures, debt, and expenditures in a heterogeneous business landscape with an uncertain future is a recipe for precarity, creating new forms of economic vulnerabilities.

How are these business owners “vulnerable?” Adapting Kirstin Dow’s work on vulnerability, it can be “expressed as a result of exposure or as a measure of coping abilities.” Small business owners are disproportionately exposed to financial and public health risks trying to make ends meet without an adequate safety net, and their coping mechanisms have been compromised as they are unable to absorb the impact of the financial downturn for the unforeseeable future. They now live with what Jérôme Bindé calls the “tyranny of emergency.” This term characterizes the everyday lives of the poor where they are unable to analyze or forecast financial futures and live day-to-day. Amid the stay-home notices and emergent civic responsibility surrounding non-essential social activities, restaurant operators have to continue thinking of new ways to attract customers, risking their health to mitigate their increasing financial loss.

At this point, small business owners are faced with three options: default, take out a government-backed loan, or borrow money informally. Defaulting has now become commonplace for many small businesses. Even with low-interest rates and delayed payment deadlines, small businesses that take loans might not recover enough profit to pay it back.

Moreover, they exist in a web of social relations that add layers of social costs. Economic anthropologist Sohini Kar’s research on microfinance institutions in India illuminates complicated kinship structures implicated in these monetary transactions. Likewise, these small business owners are embedded within a web of social relations—they might be the breadwinners in their family, have employees who they do not want to fire, or have pre-existing debts. And when choosing to default or taking a government loan becomes challenging, business owners might decide to borrow money despite the longstanding warnings against loan sharks or ah longs. Indeed, the growth of informal finance might be one of the many unintended consequences of COVID-19 if there is insufficient support for these business owners.

Tawney’s classic characterization of the rural poor refers to them standing up to the neck in water, and a ripple would be sufficient to drown them. Using this analogy, the small business owners have taken that place in water, where a wave in the form of a pandemic has come and both options of defaulting or taking out a loan could result in drowning. The insistent call to stay at home and sinking sales revenues sound the death knell for many small business owners facing a multiplicity of economic, social, and spatial stresses—they need an oxygen tank.

What’s Next?

The pandemic’s consequences will last, but the thing with time and the future is that it remains open—an uncertain future can be tied to possible remedial actions. Singapore’s policy response has thus far produced good outcomes, and Professor Danny Quah explains that this is due to a confluence of well-designed economic incentive schemes, established domestic laws, and the Singapore public’s confidence in its political and scientifically grounded leadership. The government needs to continue supporting its people, and in particular, these small business owners through targeted policies that ensure workers remain employed as much possible and help businesses to stay afloat. These strategies have significant long-term economic implications, such as preserving the aggregate stock of firm-specific capital and avoiding employer-employee mismatch.

The government is not alone—we, as the public, cannot rely on inherited economic policies or the status quo, as this pandemic calls for new responses. Consumers have to rally around supporting small businesses. Some have cited the usefulness of gift cards in creating short-term cash flow, shopping online, and encouraging local communities to do the same. One initiative, ChopeAndSave, has emerged as a directory of small businesses around Singapore that offers gift cards for purchase. Further, there should be channels to assist those most affected by the pandemic to navigate any bureaucratic processes and claim their respective packages. Landlords can heed Daniel and restaurant owners’ calls to lower the high rental fees and follow-up on promised rebates. And those affected can continue lobbying their local MPs to take action where it is most needed. Hopefully, the cooperation of civil society—staying at home, supporting local and flattening the curve—and government intervention will be succeeded by a “pent-up demand” that creates a new surge in the economy or a post-growth economy becomes an equitable norm. These cumulative acts to save lives and livelihoods involve everyone, and they can go a long way to strengthen the socio-spatial fabric that constitutes Singapore. Thus, these new vectors of vulnerability must be matched with urgency by the continued and increasing provision by the Singapore government, better civic awareness among the entire population, and expanding ethics of care.

Image Source: Today Online