[Photo: Amy Keus/Flickr]

Six years ago, a revolution toppled Tunisian President Ben Ali and the country began its journey towards becoming a democracy. But since then, has Tunisia succeeded in becoming a truly democratic state? No single narrative can adequately explain what happened in Tunisia between December 2010 and January 2011. The sequence of events was so dramatic and unexpected that no one, including senior Tunisian officials, could later give a full and authentic description of what had happened.

What can be said, though, is that Tunisians succeeded in changing the course of history with heroism and bravery. Rarely in the modern history of the Middle East and North Africa had a revolution explicitly targeted a dictator and then successfully brought an end to an unjust and authoritarian regime. The Tunisian revolution was exceptional in many ways, taking world leaders and political observers by surprise. No one foresaw that Ben Ali would end up fleeing the country, or that Tunisians would overcome their fear and shout, “The people want to overthrow the regime!”

For decades, Tunisians had suffered under Habib Bourguiba’s dictatorial regime and his successor Ben Ali’s police state. Ben Ali’s rise to power in 1987 was thought at the time to be an opportunity for the country to leave behind years of despotism and begin a brighter, freer era. Unfortunately, Ben Ali’s regime turned out to be similar to that of his predecessor. Progressive restrictions on freedom of speech and the press, and limitations on internet usage, bothered Tunisians across social classes. Corruption became “a way of life” to a certain extent, generating immense dissatisfaction and anger. In December 2010, a young man named Mohamed Bouazizi suddenly decided to immolate himself in public, protesting against poverty, unemployment, and humiliation. His desperate reaction stirred Tunisians’ own discontentment, and spurred massive protests throughout the country – first demanding more freedoms, and later calling for dismantling Ben Ali’s regime and bringing his family to justice.

Since 2011, Tunisia has been journeying towards achieving a genuine democracy. Although this journey has been bumpy, the country has succeeded in holding free and transparent elections, ratifying a new constitution reflecting the hopes of all Tunisians, and establishing democratic institutions to protect the ongoing transition. Yet many challenges remain. Although Tunisia now has a political system that enjoys legitimacy, thanks to a new constitution and transparent elections, the country’s newly established political institutions inspire low levels of public confidence.

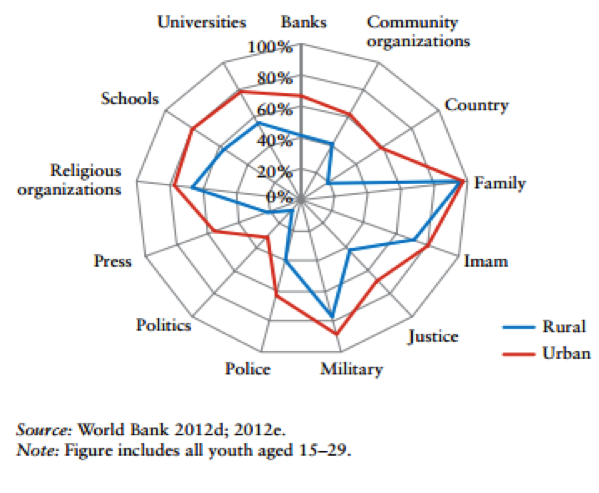

Figure 1: Trust in Public and Religious Institutions

The figure above, which shows the results of a survey conducted by the World Bank and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, reveals an important point: Whereas religious organizations, the military, and the family enjoy high levels of public trust, especially in urban areas, very few trust political institutions. There is likely a socio-psychological explanation for this: whereas those with untroubled psychological histories are often ready to cooperate with other individuals, those with negative or traumatic past experiences tend to be more pessimistic, less likely to cooperate with others, and are “inclined to be guarded or alienated,” in the words of Kenneth Newton and Pippa Norris (Newton and Norris, 1999).

To an extent, this may explain Tunisians’ lack of confidence in political institutions: Decades of dictatorship and marginalization have prevented Tunisians, particularly youth, from rebuilding their trust and adjusting themselves to their country’s new democratic environment. Accordingly, it may take years for a higher degree of trust between citizens and institutions to form – provided, of course, that democratic opportunity continues to be protected and promoted.

Low political participation and engagement

Tunisian leaders will have to work to integrate the country’s citizens into a range of political activities other than voting, and raise their awareness of the importance of active political participation. This may include creating political parties, organizing protests and marches, participating in civil society, serving on juries, and engaging in “digital democracy” by expressing one’s opinions on forums, blogs, and other networks.

Although Tunisia enjoys a certain degree of democracy, with stable political institutions that guarantee freedom and liberties, political participation is surprisingly very low. According to the 2014 World Bank report, only 17% of Tunisians aged 18-25 voted in the 2011 elections. A report published by ISIE found that just 29% of eligible voters participated in the 2014 elections. Lack of enthusiasm undoubtedly contributed to these low levels of participation, and Tunisians are now less interested in politics than they were immediately after Ben Ali’s ouster. The diminution of the revolutionary spirit and the persisting lack of confidence in political institutions has created a mood of indifference and inactivity.

A limited knowledge of politics may also be a cause of poor political participation. Only 15.7% of young Tunisians in rural interior areas consider themselves to be politically knowledgeable, and only about one-quarter of Tunisian youth in urban areas. Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi stated in an open interview with US Secretary of State John Kerry that, “One of our priorities is rebuilding Tunisians’ confidence in our political parties, our democratic institutions and our democracy by and large. Tunisian youth are desperate, and we have to fix that as soon as possible.”

Civic engagement – defined as interaction between civil society and other private and public institutions – allows citizens to directly express their needs and demands. This can take several forms, ranging from volunteering to becoming involved with nongovernmental organizations. In Tunisia, civil society plays an important role in promoting the country’s new democratic spirit. For example, the 2013 National Dialogue was an outstanding success thanks in part to the effective participation of civil society organizations, such as the Tunisian General Trade Union (UGTT). Moreover, the number of nongovernmental organizations has mushroomed in Tunisia since the democratic transition began. According to a study released by Euromed, the number of NGOs increased from 10,000 in 2011 to 15,000 in 2014. These NGOs mainly focus on issues such as poverty and exclusion in the poorer interior regions of the country.

However, the growing number of such organizations does not necessarily translate into higher levels of civic engagement in Tunisia. In fact, many young Tunisians are inactive on this front, with only 1.5% of urban youth volunteering in local or national organizations.

This lack of participation in civil society may have several explanations. First, the huge gap between the political elite and young Tunisians is widening, as many Tunisians believe their leaders have failed to meet their expectations. For instance, according to the Tunisian Statistics Data Bank, unemployment among male university graduates was 20.5% in 2016, and 41.7% for female graduates. Many young Tunisians feel that their voices are not heard, and that engaging in civil society organizations would be a waste of time and effort. Low youth civic participation in Tunisia is also reflected in their underrepresentation in non-governmental organizations.

Tunisia is making significant steps towards establishing a truly democratic system, by holding successful elections, drafting a new constitution, and forming democratic political institutions. The country’s political elite, despite their ideological and political differences, have for the most part succeeded in preventing these disputes from thwarting the revolution’s success.

Yet many barriers remain on Tunisia’s path to democracy. The lack of widespread political participation, and low trust in the newly founded political institutions, may hinder the country’s democratic transition. This may be the result of a lack of democratic knowledge, and of information about the current political system. It may also be caused by low motivation, a result of the country’s gloomy political past during the long decades of dictatorship.

Tunisian leaders should look beyond what their revolution has already accomplished, and understand that it may still end in failure if Tunisians do not continue to write their own pages in their country’s history. First, Tunisian political leaders should leave behind their traditional discourse and opt for innovative communication strategies in an attempt to bridge the gap between the political elite and citizens. Second, new programs must be implemented to boost young Tunisians’ levels of political participation. More national debates should be held on current events and government actions, and school curricula should be revised to encourage the acquisition of democratic values, on subjects such as political systems, human rights, and civic engagement.