BY JOSH RUDOLPH

Republican President Theodore Roosevelt was once shot in the chest as he stood up to give a speech. After the assailant was immediately apprehended, the bleeding but unshaken president shuffled back over to the podium and said, “It takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” He then proceeded to deliver his speech.

Today’s Republican Party has been on the defensive ever since its humiliating defeat in the 2012 election. Party leadership conceded to tax hikes on the wealthy, asked for almost nothing in return for shelving the debt ceiling debate, and now are contemplating immigration reform and gun control.

If this recent move toward the center ends up being a permanently “new GOP (Grand Old Party),” that would be good for the country and good for the party. With former President Ronald Reagan’s legacy failing to resonate with an increasingly minority and millennial electorate, the Republicans are struggling to win over a second generation in a row. Such a feat cannot be accomplished by relying on the traditional Republican stronghold of defense issues alone.

Just over a century ago, under similar circumstances, an earlier version of the Republican Party did successfully win the adoration of two back-to-back generations of American voters. In 1901, partisan gridlock reigned supreme while the aging generation of Lincoln Republicans struggled to excite the new electorate. That was when the youngest president in our nation’s history, Teddy Roosevelt, ascended to the presidency and remolded the political landscape.

In order to enjoy similar success, today’s “New Republican” Party will need to be represented by proud and loud Bull Moose personalities who are delivering a centrist policy platform that resonates with an electorate that is moving decidedly away from the GOP. Without a formidable offensive, the party risks falling out of favor with the largest generation in American history and spending thirty to forty years on the political sidelines.

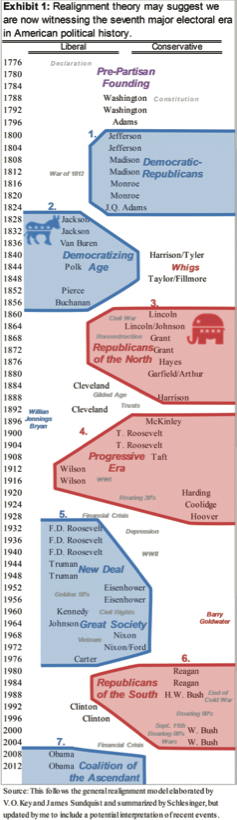

Models of American Political Cycles

In order to estimate the odds of the Republicans being relegated to minority status for an extended period, we must begin by reviewing what leading social scientists have to say about how American political cycles work.

There are two dominant theories. The first, pioneered by historian Arthur Schlesinger, suggests that every fifteen years or so (round trip of thirty years or roughly one generation), the American political pendulum swings from the liberal ambitions of public purpose to the conservative retreats of private interest (or vice versa).[i] Some GOP optimists observe that the Democrats have now won five of the past six presidential popular votes in the twenty years since 1992, and thus the Republicans are five years overdue for dominance.

But the four terms in the middle of this period—the presidencies of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush—were one of the longest expansions of private enterprise in American history. Moreover, a closer reading of Schlesinger reveals that the liberal institution-building phase tends to follow a society-rattling shock, such as the financial crisis in 2008. And even before this recent shock, toward the end of the Bush presidency, the electorate was “ready for change” away from the Republicans, the hallmark sentiment of the Schlesinger cycle.

Therefore, it is more likely that the shift toward liberal government only began in 2008, and the Schlesinger theory is more likely to suggest continued liberal dominance for at least the next two elections (2016 and 2020).

But the other dominant cyclical interpretation of American political history—the theory of generational party alignment—may paint an even starker future for the Republicans.[ii] And unfortunately for the GOP, both exit poll results and demographic data lend more support to this longer-term interpretation of the political cycle.

1. Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans

2. Andrew Jackson’s new Democratic Party

3. Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party

4. Teddy Roosevelt’s Republican Party

5. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal

6. The Reagan Revolution

Today’s open question is whether President Barack Obama’s coalition is ushering in a seventh realignment that will define the millennial political experience for decades to come. Such an outcome is certainly plausible, as a whopping 60 percent of voters below the age of thirty voted for the Democratic ticket in 2012.[iii] An Obama realignment would clearly be bad news for the GOP because generational realignments last twice as long as Schlesinger cycles—thirty to forty years—given that 80 percent of Americans historically stay loyal to the political party that was dominant when their generation came of political age. That is, researchers find that party identification is only highly malleable the first two or three times a given voter heads to the polls. After that, the tendency to loyally cast another ballot for the same party every four years “locks in” as a lifelong habit. Given the surge in millennial voting in 2008 and 2012, the last chance for Republicans may be 2016.

If this is not reason enough for the Republicans to hit the panic button, the millennials are not the only growing segment of the electorate that is increasingly voting for Democrats.

Coalition of the Ascendant

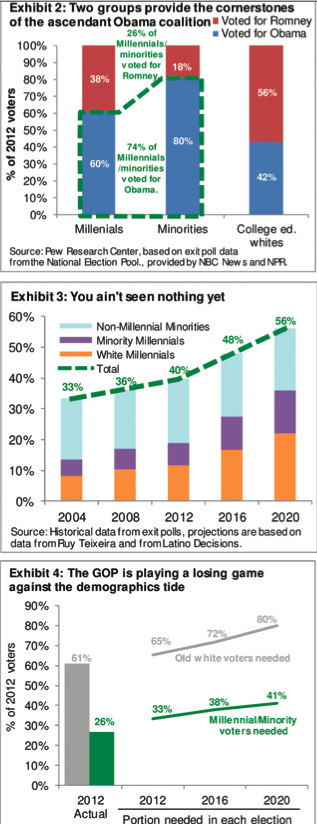

In the realignment model, critical elections tend to split the electorate along more dimensions than age alone. National Journal Editorial Director Ronald Brownstein has pointed out that in 2008, Obama’s “coalition of the ascendant” was anchored by three groups, each of which is increasing in numbers faster than the general population—young people, minorities, and college-educated Whites (particularly women).[iv]

Collapsing the millennials and minorities into one group, 74 percent of them voted for Obama in 2012 (see Figure 2), representing 40 percent of all voters. Given demographic trends, this share of the electorate is expected to increase to 48 percent and 56 percent in 2016 and 2020, respectively (see Figure 3).

The numbers look no better for Republicans when considering how much of this growing block of millennials and minorities the Republicans would need to win. In 2012, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney only won 26 percent but needed 33 percent (along with the 61 percent of older White votes he captured). This hurdle is expected grow to 38 percent and 41 percent in 2016 and 2020, respectively (see Figure 4).

To look at the problem another way, consider the share of the remaining middle-aged and elderly White voters the GOP needs to attract to win the popular vote. In 2012, a historically high 61 percent of them voted for Romney, but he needed 65 percent to win (given 26 percent of millennials and minorities); the hurdle climbs to 72 percent and 80 percent, respectively, in 2016 and 2020.

The real message in these numbers is that the GOP’s political strategies that worked well in the past will not succeed with the newly emerging electorate. From former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay’s famous legislative strategy of aiming for House votes to be as close to fifty-fifty as possible (pushing legislation as conservative as possible) to former White House Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove’s brilliant electoral strategy of foregoing the center and focusing instead on getting the base out to vote, these strategies certainly produced a string of conservative victories in a nation more evenly divided between the two party ideologies. But fifty-fifty strategies will never lead Republicans to win over either 80 percent of elderly White voters or 40 percent of millennials and minorities.

These numbers alone should be enough to scare any future Republican candidate into rethinking the party’s policy platform from the ground up. But it’s even worse than that. The GOP was facing a challenging electoral map even before the rise of this new Democratic coalition. Let’s look at how the electoral map has shifted over the past fifty years.

Going Coastal

The results of the past twelve elections (see Figure 5) are a tale of two Republican Parties. First, the GOP won five of the six elections beginning with Richard Nixon in 1968 through George Bush in 1988.[vi] After that, the Democrats won the popular vote in five out of six elections (1992 to 2012). Which begs the question: what happened to the Republican Party after 1988?

There are a few potential answers to this question. One is that the idealist generation of baby boomers grew up from being mere impassioned voters to become highly ideological lawmakers, epitomized by the rise of Newt Gingrich, who became Speaker of the House in 1994.

Another event that remolded the political landscape at that time was the end of the Cold War. The absence of any existential military threats interacted with the rise of the boomers to produce one of the most highly partisan political environments in U.S. history. The end of the Cold War also presented a political problem for the Republicans, who are generally perceived as tougher on defense issues. With the GOP needing new public causes to identify with, the party courted Southern Evangelicals and adopted a handful of moralist crusades, which were particularly problematic with socially moderate voters in coastal states. Broadly, the agenda was anti-immigration, anti-abortion, anti–gay rights, anti–drug legalization, and anti–environmental protection.

This is not exactly a platform that many Californians, for example, can stomach. The result is that the Golden State voted Republican in all six elections before the Cold War ended and voted Democrat in all six elections since then (see Figure 5).[vii] With fifty-five electoral college votes, California is the cornerstone of the 244 electoral college votes consistently won by Democratic presidential candidates in the past six elections. Unable to rely on the highly populated coastal states, the Republicans are forced to start off every election with only 169 electoral college votes in reliably red states.

Among the 125 electoral college votes claimed by neither side (the swing states) in recent electoral maps,[viii] Republicans must win 81 percent of them while the Democrats only need 21 percent to reach the 270 votes needed to win. For example, the Democrats can win a nationwide election with just their reliably blue states plus either Florida alone or the combination of Ohio and Iowa, while the GOP could win all three of those swing states and still be only half way to the 81 percent of all swing state votes they need for victory.

This math suggests that the Republicans have been playing a losing game since 1992. If they fail to quickly and dramatically reinvent the game by embracing the types of policies and candidates that can appeal to young people and minorities, they risk spending a generation on the sidelines.

But it does not have to be that way. American history provides examples of political parties successfully reinventing themselves and winning over a second generation in a row. However, only a dramatic shake-up of the GOP—from the personalities to the electoral map to the policy platform—will accomplish this.

A New Republican Personality: Bull Moose, Not Pretzel

Given the battered image of the Republican Party after the 2012 election, the first step toward nationwide acceptance must be to establish credibility as reformists. Again, history offers a few examples. The only reason Teddy Roosevelt became vice president—against the wishes of the William kMcKinley campaign—was that he wouldn’t kowtow to the conservative establishment, so they wanted him out of the powerful New York governorship. He wasn’t afraid to take on his own party’s corrupt politicians or the large corporations that supported the party. Likewise, Bill Clinton established credibility as a “New Democrat” with his “Sister Souljah moment,” and former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair only truly became “New Labour” after he attacked his own party’s definition of socialism.

In the recent election, the social conservatives gave Romney plenty of chances to establish himself as a reformer. Most notably, the Republicans running for Senate gave morally and scientifically wacky justifications for not legalizing abortion for rape victims, saying that the female body doesn’t get impregnated by “legitimate rape” (Todd Akin) and that if the woman does get pregnant from rape it was “something that God intended” (Richard Mourdock).[ix]

But rather than using such extreme blathering as a launching pad to establish credibility as a “New Republican,” Romney allowed the fringe right to use him as a platform for its radical views. In order to get through the primaries, Romney had to transform his traditionally moderate demeanor into a pretzel of sorts, contorting his own views in deference to the conservative base.

If the Republicans want any chance of picking up 40 percent of the millennial/minority portion of the electorate, they need a young moderate who will loudly and confidently lambast extremists on either side of the aisle as being nonsensical and out of their minds. Does the Republican Party have any young and tough up-and-coming moderates who are bold enough to speak out against the establishment?

Some expect New Jersey Governor Chris Christie to be the Republican frontrunner for 2016. He has recently come under criticism by the conservative establishment for calling the Republican-controlled House “disappointing and disgusting to watch” for failing to provide relief for Hurricane Sandy and for calling a National Rifle Association (NRA) advertisement “reprehensible” for saying that Obama is an elitist hypocrite for allowing his children but not yours to be protected by firearms.[x],[xi] Christie is also known for shouting at hecklers and calling disrespectful reporters morons or idiots. It’s hard to imagine him turning into a deferential pretzel in order to snake through the Republican primaries. The GOP needs a break from the ordinary, and Christie may bring the right Bull Moose personality along with the right moderate views.

A New Republican Platform: Socially Moderate Problem Solvers

In order for the Republicans to break out of their mathematically losing political strategies, they also need a broadly appealing policy platform. Looking at exit poll data, the majority of the electorate generally seems to favor the very social liberties that Republicans have crusaded against, especially when looking at the age breakdown. Between 60 percent and 70 percent of young voters support legal status for illegal immigrants, gay marriage, and legalized abortion (see Figure 6).

Turning down the volume on the GOP’s moralist battles might also help the party poll well on the coasts. If the Republicans could take California away from the Democrats, the GOP would start out with thirty-five electoral college votes more than the Democrats, as opposed to starting out with seventy-five votes less than them (before even including any gains that would come in the East Coast states).

But beyond fixing the GOP’s social platform, an overdue and defensive reaction, the party must also go on the offensive, casting conservatism as a source of solutions to the problems faced by minorities and millennials. These problems might include the rising costs of higher education and health care that have absorbed two decades worth of middle-class wage gains, a public school system that has not significantly enhanced educational attainment since the 1970s, and a financial sector that monopolizes the country’s human capital while taking publicly subsidized bets with its financial capital.

Only by establishing credibility both as social moderates and as pragmatic problem solvers can a “New Republican” Party appeal itself to the majority of a second generation of Americans in a row.

Can a New Republican Party Stave Off Realignment?

President Obama has been playing plenty of his own offense this year, setting out his vision and priorities for a more perfect union. His momentum seems to show a confidence that the age of Reagan has come to an end and the Democrats have been chosen to tackle the new problems of our day.

An alternative interpretation of the recent election is that no such mandate was rendered and the electorate was simply unimpressed with the unreconstructed Reagan Republicans. Under this view, the more stubborn conservatives might simply hope for better luck next time.

While only time will tell which of these two readings is correct, the one thing we do know is that failing to redesign a credible “New Republican” Party is a sure way to ensure that Obama’s interpretation comes true. It will take more than immigration reform and gun control. It will take solutions to problems such as the slow economic recovery, the fiscal crisis of the entitlement state, and gridlocked political partisanship.

And it will take a Bull Moose.

Photo source here.

Josh Rudolph is a 2014 Master in Public Policy candidate at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, focusing on international trade and finance. Before coming to the Harvard Kennedy School, he was an investment banker and fixed income strategist.

[i] Merrill III Samuel, Bernard Grofman, and Thomas L. Brunell. 2008. Cycles in American national electoral politics, 1854-2006: Statistical evidence an an explanatory model. American Political Science Review 102(1).

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 2012. Young voters supported Obama less, but may have mattered more, 26 November.

[iv] Brownstein, Ronald. 2012. Coalition of new, old equates to Obama win. National Journal: The Next America.

[v] Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 2012. Changing face of America helps assure Obama victory, 7 November.

[vi] U.S. Electoral College. n.d. Historical election results. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

[vii] 270 to Win. n.d. California electoral votes.

[viii] Mercurio, John, and Molly Levinson. 2004. Small states could swing electoral college. CNN, 22 October.

[ix] Moore, Lori. 2012. Rep. Todd Akin: The statement and the reaction. New York Times, 20 August.

[x] CBS News. 2013. Gov. Christie: House GOP, Boehner “disappointing and disgusting to watch.” Video, 2 January.

[xi] Killough, Ashley. 2013. Chris Christie rails against NRA, calls ad “reprehensible.” CNN, 17 January.