BY AMELIA POLLARD

After a decade of amassing influence, Facebook has unveiled another way to remain a financial heavyweight not only for digital markets, but for society. On June 18, Mark Zuckerberg announced the birth of a new form of blockchain-backed cryptocurrency dubbed “Libra”—a potential monetary revolution that’s raised eyebrows, particularly in the wake of the numerous data breach accusations brought against the company in the past year. Most notably, the structure behind Libra—the “Association” and Council created as governing bodies—are much closer in girth to the European Union than pre-existing, often volatile, cryptocurrencies. With the number of global transactions annually only second to that of the U.S. dollar, the Euro is an appealing model for Libra.[1] The success of the Eurozone in the last two decades is being harnessed by Libra as a roadmap in creating this global currency. But there are concerns that emerge with the creation of a privatized union that has the underlying and pervasive goal of profit instead of public interest. Specifically, it’s unclear how to regulate it.

The newly-minted currency, named after the Latin translation of “pound,” is spearheaded by Zuckerberg with an ambitious agenda. The appeal of Libra is two-fold: it seizes power from Wall Street in eliminating the capricious effects of speculation, while simultaneously increasing the agency of citizens in developing countries with a safe and reliable way to transfer funds (particularly for migrants sending remittances home to loved ones). As a result, Libra seems to be the answer for every global citizen—all you need is a smartphone. With international accessibility and negligible transaction fees, the currency is a universal financial solution. Looking to transfer many millions of dollars from New York to Geneva? Libra. Hoping to invest in a goat for your family in Kashmir? Libra.

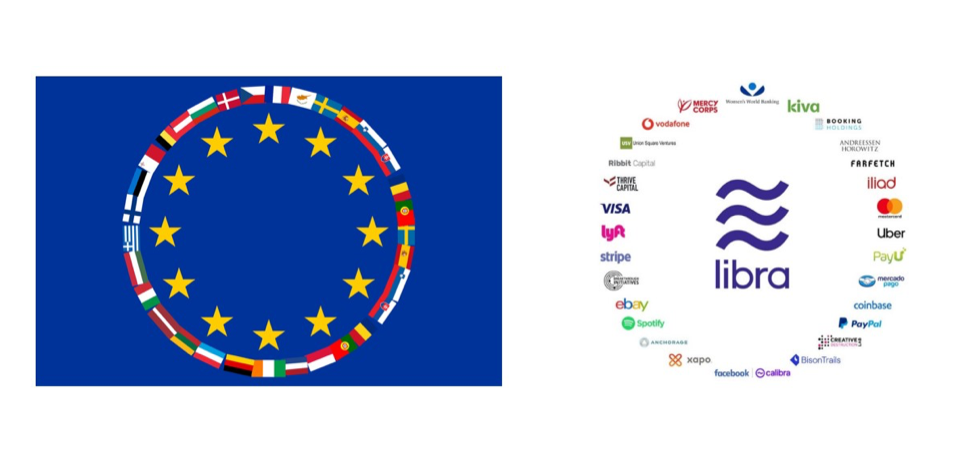

But the tech-backed cryptocurrency and subsidiary association, Calibra, is forging a new frontier: it’s blurring the line between private and public enterprise in an unforeseen way. The 28-firm-strong alliance is a novel business model of private companies joining forces with the goal of creating a communal good. The group is comprised of companies ranging from Uber to Visa, ensuring that the greatest modern-day tycoons will have a seat at the table. The alliance mirrors pacts that are often formed by countries—not companies—in the interest of bolstering resources and voices to generate compounded negotiating power. Of all the current economic communities in place, the most strikingly similar to that of Libra is the European Union. And more specifically, from a currency perspective, the Eurozone.

The E.U. has had an evolutionary history stemming from the late 1940s, when rebuilding the war-ravaged continent relied on economic coordination. After decades of treaties and summits, the euro was officially launched in 2002, with the largest-ever currency overhaul in history. Although the Eurozone is a separate entity from the E.U., there are many countries that are participants of both. The structure of the E.U. has eerily similar qualities to that of Libra. Each union has the same number of members, a powerhouse orchestrating its trajectory (Germany and France for the E.U., Facebook for Libra) and an enormous constituent base (guaranteeing power in numbers).

The overarching structure to all of this is the Libra Association, a Swiss not-for-profit membership organization that serves as a vessel for the “validator nodes” (the name denoted by Libra for participatory members) to coordinate among themselves. The association is governed by the “Council” which includes a representative from each member company. This governing body uncannily mirrors that of the European Council, the branch of the E.U. which determines the direction of the union and is comprised of the heads of state or government of each member country.

But that brings some reason for concern. The first worry is its size. The number of companies backing Libra is already significant, but this is just the beginning of the tally. According to the association’s White Papers, the group is hoping to attract as many as 100 additional partners by its release in 2020. The coalition already represents at least $160 billion in collective annual revenues, with Facebook’s revenue surpassing the others by a substantial margin with $55.8 billion in 2018. The conglomerate is therefore coming onto the currency scene with a strident force of softpower, a phenomenon classically associated with the E.U. This includes a group with cultural or economic pull which has negotiatory power even when it’s lacking official regulatory backing.

Similar to the E.U., the structure of the alliance is already bureaucratically nebulous, even in its nascent stage. With the creation of what the organization calls an “ecosystem” for Libra, it’s creating a universe of its own. This “ecosystem” renders the other financial ecosystems, those regulated by the Federal Reserve and other economic infrastructures, paltry—making Libra practically unstoppable.

The “flags” of both the European Union and Libra. Side-by-side, they’re strikingly alike.

In an age in which people are all but physically chained to their screens, Libra is yet another way in which smartphone users will depend on Big Tech. The rollout of Libra is the next keystone of Facebook’s development strategy to not only stay profitable, but remain indispensable. The new currency will be released and targeted to a “constituent base” larger than any country or pre-existing union’s population. Users of Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, the Association’s makeshift cohort of constituents, will be lured to register for the cryptocurrency in 2020 when it’s officially released to the public. Promises of low transaction fees and an appealing interface will attract users to switch from Chase or Bank of America, while those from unstable economies will be leaping at their first chance of a secure financial service; effectively rendering Libra effortlessly marketable. Of the three major social media platforms, there are 2.38 billion monthly active users on Facebook alone. This makes Libra’s constituent base significantly larger than China’s population of 1.4 billion, and nearly five times larger than the entire population of the E.U.

The fact that the Libra Association and the Eurozone seem so structurally similar is not a coincidence. In recent years, the E.U. has consistently been ahead of the curve in drafting, and passing, regulatory legislation that holds tech companies accountable in securing European citizens’ data and privacy. In 2016 the European Parliament passed a suite of laws, including the General Data Protection Regulation, which allowed heavy fines for any violations. Last September, Facebook was fined $1.6 billion for a data breach, and in March, Google was fined a record of $1.7 billion for violating antitrust legislation. As a result of its robust regulation, the E.U. has securely put itself on these tech moguls’ radar. Modeling Libra’s governing structure off of the E.U. may render the European currency less important if the cyryptocurrency successfully takes off in doing everything the Euro can do and then some. The softpower that enables the E.U. to pull weight in international negotiations might become markedly less important.

But the U.S. is now trying to play catch-up. In the last month alone, the Federal Trade Commission has pinned Facebook with a $5 billion fine in the wake of the Cambridge Anayltica scandal—a record for the FTC. In the midst of congressional hearings regarding Libra that began on July 16, U.S. financial leaders have continually expressed apprehension regarding the cryptocurrency. Jerome H. Powell, the chair of the Federal Reserve, said that the central bank had “serious concerns” about the security implications of Libra.

Libra’s proposals are grandiose and radical. If successful, the currency shift could mean a complete restructuring of international financial institutions as we know them. As the United States and other countries are desperately trying to review regulatory measures needed to keep the largest tech companies in check, Libra might catapult these firms into an unprecedented position of power. Passing regulation to harness monopolistic power has traditionally moved at a glacial pace. The potential repercussions from Libra, though, pose a novel threat to the future regulatory power of financial institutions. The proposal is ambitious. Never before has a governing body like the EU been faced with a proposed privatized governing structure that could potentially compete with the Eurozone’s very function of running a unified currency. If restrictive measures are not taken in the months before Libra’s projected launch of early 2020, the world risks facing not just a clear monopoly, but an unchecked monocurrency.

Amelia Pollard is a senior at Middlebury College where she is majoring in Political Science and French. She recently completed a semester studying at Sciences Po in Paris and is currently an Editorial Intern at Foreign Affairs magazine. She has previously researched and written about GAFA’s role in environmental management. Follow her on Twitter: @ameliajpollard

Edited by Vandinika Shukla

Photo by Pixabay

[1] “Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2016” (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. December 11, 2016. p. 10.