Colombians were enraged. On May 1st, 2021, amid the third wave of covid-19 cases, a national protest took place where more than 300.000 people blocked roads and cities for more than 50 days. Violence and death sprang on the streets, polarization on social media proved a cracked society, road blockages paralyzed the private sector, and food, medicine, and gasoline supply chains were running short.

The reasons behind this social unrest lie in historical inequality and lack of opportunities for the young and poor. However, the protests’ trigger was explicit: a new fiscal reform that would affect the middle-high class. Some academics would agree that in general, this was a technically convenient fiscal reform for Colombia.[1] In the end, the reform was retired, and the Minister resigned.

By the observed outcome, the 2021 tax reform is a case in point to show what lessons can be drawn from the political execution of difficult institutional changes. Friction can be reduced by reaching an agreement through strategic actions and good timing.[2] Key factors revolve around media management, institutional alignment, and stakeholders’ involvement.

The core of the reform

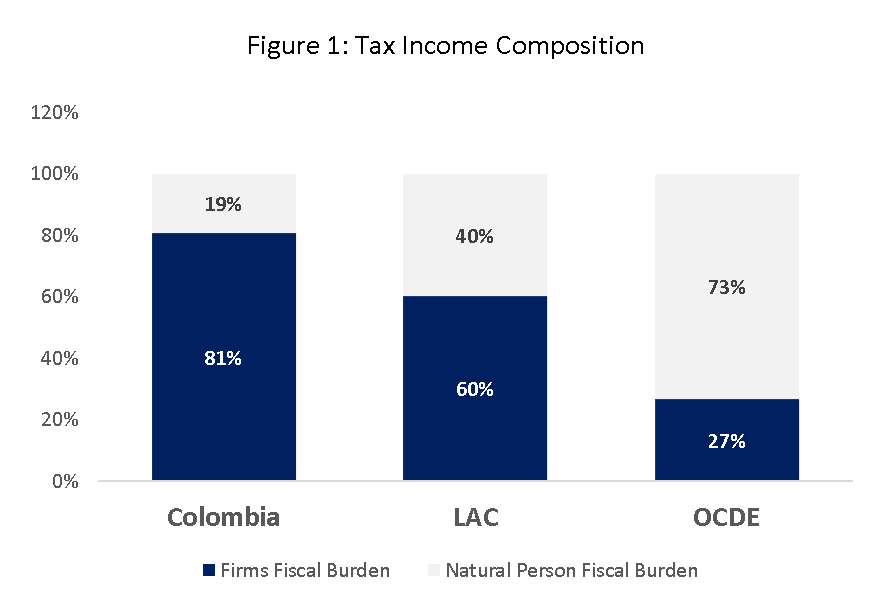

Colombia is a country of approximately 50 million people where 3 million pay taxes[3]. The lack of individual contributions has the effect of leaning the fiscal burden on firms. Figure 1 shows that 19% of total income tax comes from individuals, a low proportion when compared to Colombia’s peers in Latin America (40%) and more critical when compared to the OECD (in which Colombia is a member) which has an average of 73% of income charged on natural persons.

The fiscal reform attempted to drag Colombia to OECD standards by expanding the tax base from the richest 3%[4] to the richest 7%[5]. Moreover, the reform attempted to tax pensions of the richest 1% (in the current status quo, less than 0,1% pay marginal contributions to their monthly pensions). It also attempted to eliminate benefits on Value Added Tax (VAT) for some basic products like coffee and chocolate to finance a subsidy of the VAT targeted for the poorest 40% of people[6]. Overall, these resources would finance the safety net deployed by the government during the pandemic to bring social protection to the most vulnerable, and to finance public spending for economic reactivation.

Balance between political and technical

The first person that labels the feasibility of tax reform is the President. She/he gets a rough idea of the reform’s core principles and frames his/her judgment in the country’s context. The President should consider the ability of the government to use existent political capital or to create a new one for approving the reform. This requires the capacity of getting actors with political power to be on one’s side[7]. The president should realistically calculate a balance between his/her political odds and the best reform, which his team believes to be the most convenient. If the best project is labeled as impossible, the Ministry of Finance knows that second-best principles need to suit political capabilities.

Selling a dream

A leader needs to publicly frame a problem[8]. This means diagnosing an urgent matter and making a public motivational call to action. This will allow an alignment around a common discourse even among its political detractors and media. While the discourse settles, work needs to be done towards mobilizing allies and structuring the technical part of the reform.

Tightening internal execution

The President should state clear roles and be able to make his team understand that the attempted fiscal reform is the most important policy for the government. If all the government entities prioritize and participate at a high level in the reform’s discussions, multi-sectorial inputs can be used as negotiation tools with interest groups.

With an aligned team, the project should be theorized in consistence with the settled public discourse and its political possibility. But the process should not come exclusively from within the government for two reasons: at a micro level, iterating from a finished product can exhaust and discourage staff. But most importantly, fewer frictions will arise when interest groups take accountability for the reform by participating in its elaboration, so a participatory process is needed.

From the doors out

An exercise of graphically identifying stakeholders’ preferences, understanding their worldviews, and coming up with a pool of negotiation options is a necessary practice to identify key leverage points. As a basic matter, the government’s coalition party support should be consolidated prior to any engagement with external actors. With a unified basis, collaboration[9] with more distant political, economic, and social actors could be achieved by involving them in the project’s structuring, especially those that partially agree with one’s position.

Negotiation with those who are not willing to enter the collaboration process is essential. This exercise shouldn’t spin around whether to go forward with core reform points but rather should focus on how these “paint-points” can be offset by benefits the reform may bring. Fresh political support should be sought by identifying whose voters will the reform benefit, while social support should be pursued by meeting organized groups that could potentially defend the reform as they would benefit from it.

Every new support is a victory and should be communicated to the public opinion as a step closer to achieving the dream. Finally, the government should anticipate misinformation with two strategies: first, be strategic enough on collecting and communicating significant support before groups that will not benefit at all do. And second, the President and his/her key Ministers should communicate the project’s content in an understandable and consistent way. Public disagreement among the government official will mortally wound any attempt to change institutions from within.

References

Finance, M. o. (2021). Fiscal Reform 2021. Bogota.

Hofstetter, F. &. (28 de Apri de 2021). Reforma tributaria para ciudadanos…no para dummies. Leopoldo Fergusson Videos. https://www.leopoldofergusson.com/videos.

R.D. Benford, D.A. Snow, Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment

D.F. Pacheco, J.G. York, T.J. Dean, S.D. Sarasvathy, The coevolution of institutional entrepreneurship: a tale of two theories

M. Perkmann, A. Spicer ‘Healing the scars of history’: projects, skills and field strategies in institutional entrepreneurship Organ. Stud., 28 (7) (2007)

[1]Hofstetter, F. &. (28 de Apri de 2021). Reforma tributaria para ciudadanos…no para dummies. Leopoldo Fergusson Videos. https://www.leopoldofergusson.com/videos.

[2] M. Perkmann, A. Spicer ‘Healing the scars of history’: projects, skills and field strategies in institutional entrepreneurship Organ. Stud., 28 (7) (2007)

[3]Finance, M. o. (2021). Fiscal Reform 2021. Bogota.

[4] Finance, M. o. (2021). Fiscal Reform 2021. Bogota.

Hofstetter, F. &. (2021, Apri 28). Reforma tributaria para ciudadanos…no para dummies. Leopoldo Fergusson Videos. https://www.leopoldofergusson.com/videos.

[7] D.F. Pacheco, J.G. York, T.J. Dean, S.D. Sarasvathy, The coevolution of institutional entrepreneurship: a tale of two theories

[8] R.D. Benford, D.A. Snow Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment Annu. Rev. Sociol., 26 (1) (2000)

[9] D.F. Pacheco, J.G. York, T.J. Dean, S.D. Sarasvathy, The coevolution of institutional entrepreneurship: a tale of two theories

Alejandro Chirinos holds a bachelor’s degree and MSc. in Economics and a MSc in Industrial Engineering. He is an MPA-ID candidate 2023 at the Harvard Kennedy School. His career has spun around media and infrastructure, where he has performed as advisor for the Vice-President of Colombia, investment banker of Public-Private Partnerships, and public official at the National Infrastructure Agency (ANI) and the Infrastructure Development Bank of Colombia (FDN). Alejandro is co-editor in chief of the Latin American Policy Journal.

Instagram: @alejandro.chirinos9