In the last decade, we have witnessed worldwide policy and law changes regarding sexual and reproductive rights. In some countries, such as the United States, federal and state-level legal decisions evidence a withdrawal of gender equality policies[i] regarding sexual and reproductive autonomy. At the same time, contentious politics and legal efforts have led to their design and implementation in other areas of the world, especially in Latin America, which has been called the Green tide. In countries such as Colombia[ii] and Argentina[iii], political institutions such as the Court and Congress have developed legal mechanisms supporting abortion and women’s physical autonomy.

Historically, feminist and women’s mobilization have risen locally; local movements have been present in different countries using the resources and capacities they build in the field. Nevertheless, the global north served as the epicenter of the feminist wave during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Aguilar Barriga 2020; Crossley et al. 2012). The fights for political participation and sexual and reproductive rights consisted of protesting, court appearances, and petitions by European and united states women’s groups. Today, the feminist and women mobilization processes and dynamics have shifted, making the whole world look to Latin America as the new feminist force leading the feminist demonstrations (Carlsen 2022).

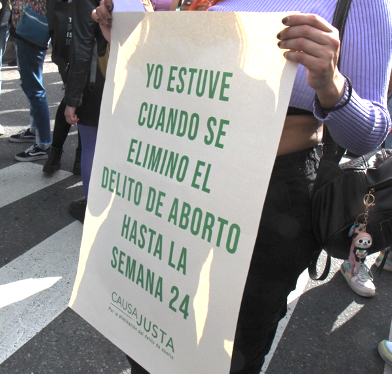

Bogotá, Colombia. March 8, 2022

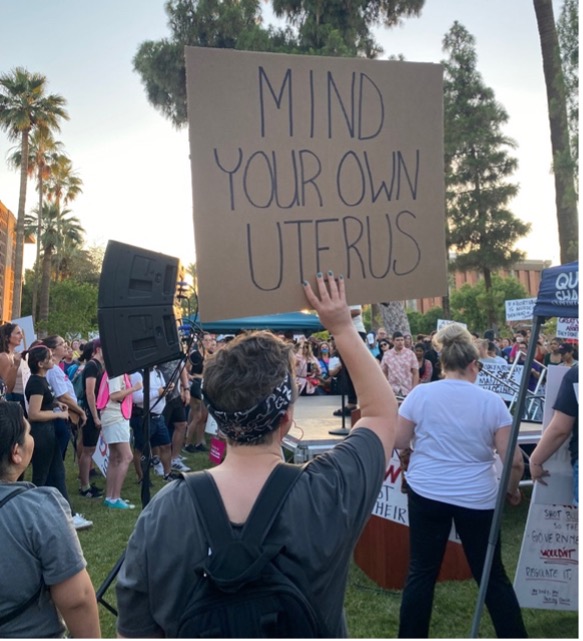

On June 2022, the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade[iv], affecting every person that can potentially get pregnant, especially in states that already have laws criminalizing or banning abortion leading to mobilizations in different states. On the other hand, the ‘Purple’ and ‘Green’ tides have generated massive women’s mobilization; the former demands human rights for women, and the latter demands access to sexual and reproductive rights in Latin America.

In the first case, we saw different interest groups reunited in the cities and protesting in medium-sized gatherings with billboards and slogans in the Spring and Summer of 2022 (McCleary and Yan 2022). Abortion rights advocates in different states have used ballot initiatives, mobilized voters, and gained support from donors (Zernike 2022) to maintain reproductive rights in the political agenda and access to sexual health services and advance state and federal laws and policies to protect sexual and reproductive rights (Fried 2013). So, in this country mobilization and demonstrations are supported or are part of federal and state legal strategies (Salganicoff and sobel 2022). Moreover, multiple advocates in the United States have advocated for laws and policies protecting sexual and reproductive rights at a local level (Lynch et al. 2022). Still, there is not a high degree of mobilization compared to Latin America, in which symbols and protest go hand in hand with constant and systematic art, cultural, and political demonstrations on the streets.

In the second case, large-size gatherings of Latino-American women paint the streets green, singing, using billboards, graffiti, among other confrontational actions. Most of the protesters in Latin America are young urban women, and we see different uses of contentious politics, from artistic demonstrations to institutional building takeovers (Infobae 2021). Also, this mobilization is part of a transnational network of efforts by Latino women’s organizations that have diffused from the north (Mexico) and the south (Argentina) to the rest of the region.

Bogotá, Colombia. March 8, 2022

It is a fact that some conservative political actors in Latin America are looking at the United States to argue against gender progressive policies; at the same time, pro-choice activists have looked to the mobilizations in countries such as Colombia, Argentina, and Mexico. It is powerful to see political leaders[v] in the global north using symbols such as the green bandana and feminist songs created and established by grassroots feminist Latin American groups[vi].

There is a divergent political engagement between women in these regions regarding how to guarantee their rights which means different political actions, strategies, and mobilization efforts. Which are the factors that determine differential engagement in contentious politics by women? Why is the global south today the epicenter for feminist mobilization after it was historically situated in the global north?

Several reasons can explain the difference in political engagement toward sexual and reproductive rights. A broad body of research has attempted to comprehend social movement origins and growth over time. According to theory resources (Edwards and McCarthy 2004; McCarthy and Zald 1977a, 1977b), grievances (Staggenborg 2021), and windows of opportunity (Tarrow 1998) have been some of the explanatory variables. But identity and structural conditions also influence why women engage differently in countries such as Colombia and the United States.

First, some structural and historical dynamics have set a culture of local and grassroots activism: Latin America has a strong and long history of mobilization caused by civil conflict and authoritarianism that has led to mobilization claiming for democratization, there is a high distrust toward the state and government institutions, and deep social-economic inequalities have been the root of local and transnational mobilizations that reinforce their other against neoliberalism (Strawn 2009). In the United States, there is less distrust in the government compared to Colombia, Mexico, and Argentina.

Table 1

| Country | More than half of politicians are involved in corruption | All politicians are involved in corruption |

| United States | 36.3% | 6.1% |

| Mexico | 38.4% | 32.5% |

| Argentina | 40.4% | 28.2% |

| Colombia | 45.5% | 30.8% |

Source: American Barometer – LAPOP from Vanderbilt University

According to the American Barometer, the average number of interviewees who believe more than the half of politicians are involved in corruption for 2021 was 36.3%.98 in the United States, 38.4% in Mexico, 40.4% in Argentina, and 45.5% in Colombia, and the percentage that believe that all politicians are involved in corruption was 6.1% in the United States, 32.5% in Mexico, 28.2% in Argentina, and 30.8% in Colombia.[vii] These figures indicate there is a high level of belief that politicians and state institutions are corrupt in the surveyed Latin American countries, as more than 50% of the people that surveyed firmly believe that there is high rates of corruption. By contrast, most people surveyed from the United States believe that more than 50% of politicians are honest. This is a factor influencing why women choose to use nonelectoral forms of political participation; there is a deep distrust toward the states and the politicians. The low levels of distrust in United States compared to the other countries could explain why grassroots movements and activist trust in legal strategies alone to fight for reproductive rights. In contrast, most women activists interviewed in Colombia and Mexico agreed that there is a need to complain legal actions with street mobilizations to generate real and effective transformations[viii].

Second, transnational dynamics in the region, influenced by the social media uprise in the last decades, have made the mobilization stronger by reinforcing group consciousness for women. In my current fieldwork research, I have identified that many women that are part of grassroots or human rights organizations fighting for human rights refer to the green tide as a political dynamic that has made women realize they are not alone. As one of the interviewees explained, referring to her own experience in becoming engaged in grassroots movements, “when one begins to talk about gender, knowing that world, also of feminism, one starts gathering and building a reconnaissance map; we begin to identify each other, and that generates a bond.” (Interviewee_1C 2022).

Phoenix, Arizona, United States. May 14, 2022

Third, identity is a central factor explaining why mobilization differs in the United States and Colombia. Collective identity correlates with increased minorities’ democratic representation (Weldon 2011), and Emotions have proven to be a potent trigger for group mobilization (Phoenix 2020). Colombian and Mexican women have been grouped by emotions such as anger, sadness, fear, and happiness triggered by the feminicides numbers and the state’s lack of success in addressing gender violence. Several women leaders I interviewed[ix] agree that the green wave has united them and made them feel less alone in the fight.

In this case, group consciousness is part of the idea that the fight for human rights is shared because of the female condition that situates women in a subaltern position and the perception of threat. Their life for being born or identified as females is at constant risk. According to UNFPA data in the United States in 2018, 4,2%[x] women were subjected to violence by a current partner or former partner. Whereas in Colombia 11,9% and Mexico 9,9%[xi]. This does not mean that United States women are not at constant risk of physical abuse; the United Nations reported that in 2008 500 women were raped daily (Manjoo 2011, 5). But the perception of threat and risk of violence seems to be higher in countries such as Argentina and Mexico where social media activists highlight violence against women daily.

The perception of threat and risk for being women has increase in the last years in Latin America due to a more continual visibility and monitoring. This was potentiated by the conceptualization followed by the criminal typification of feminicide as the act of killing a female because of misogynic reasons and as part of structural and systematic violence toward women because of gender and sexual inequality social dynamics (Meneghel and Portella 2017; Lagarde 2004). In the United States, women and other groups are fighting for sexual and reproductive rights, and the right to privacy and physical autonomy. The threat for women in the United States is the loss of body autonomy; for Latino-American women, the risk is losing their life.

Today, from Iran to Argentina, women from the global south are an example worldwide. They are mobilizing and transforming the contentious global dynamics for women facing repression and demanding inclusion and political change. In England and the United States, women were the leaders of the suffragette movement and the movement for women’s rights up to the 70s; today, we are facing setbacks on women’s rights globally, and it seems that the women in the south are the ones leading the parade for women physical, economic, and political rights.

___________

Citations:

[i] Gender progressive policies are defined by Htun and Weldon as the ones that aim to disarticulate power relations that reproduce male and masculine privileges while situating the female and the feminine in a subordinated position. (Htun and Weldon 2010, 208)

[ii] (International 2022)

[iii] (Watson 2020)

[iv] (McCammon and Totenberg 2022)

[v] (Noticias 2019)

[vi] https://twitter.com/AOC/status/1540369148798197762

[vii] https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/raw-data.php

[viii] I conducted interviews between March 2022 and November 2022 of different women leaders for my dissertation which is in development.

[ix] I conducted interviews between March 2022 and November 2022 of different women leaders for my dissertation which is in development.

[x] https://pdp.unfpa.org/apps/a4b5d5751a834c7d84019132b3326409/explore

[xi] There is not data in the United States to compare feminicide, there is the reason why I took intimate partner violence.

Bibliography:

Aguilar Barriga, Nani. 2020. “Una aproximación teórica a las olas del feminismo: la cuarta ola.” FEMERIS: Revista Multidisciplinar de Estudios de Género 5 (2). https://doi.org/10.20318/femeris.2020.5387.

Carlsen, Laura. 2022. “Green Tide Rising in Latin America.” The Indypendent. Last Modified August 17, 2020. Accessed December 20, 2022. https://indypendent.org/2022/08/green-tide-rising-in-latin-america/.

Crossley, Nick, Gemma Edwards, Ellen Harries, and Rachel Stevenson. 2012. “Covert social movement networks and the secrecy-efficiency trade off: The case of the UK suffragettes (1906–1914).” Social Networks 34 (4): 634-644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2012.07.004.

Edwards, Bob, and John D McCarthy. 2004. “Resources and Social Movement Mobilization.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule and Kriesi Hanspeter, 116-152. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Fried, M. G. 2013. “Reproductive rights activism in the post-Roe era.” Am J Public Health 103 (1): 10-4. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301125. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23153156.

Htun, Mala, and S. Laurel Weldon. 2010. “When Do Governments Promote Women’s Rights? A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Sex Equality Policy.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (1): 207-216. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592709992787.

Infobae. 2021. “Familiares de víctimas de feminicidio y colectivos feministas tomaron las instalaciones de la CNDH.” Infobae. Last Modified September 23, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2022. https://www.infobae.com/america/mexico/2021/09/23/familiares-de-victimas-de-feminicidio-y-colectivos-feministas-tomaron-las-instalaciones-de-la-cndh/.

International, Amnesty. 2022. “Colombia: Decriminalization of abortion is a triumph for human rights.” Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/02/colombia-decriminalization-abortion-triumph-human-rights/.

Interviewee_1C. 2022. Fieldwork interviews in Colombia.

Lagarde, Marcela. 2004. “Por la vida y la libertad de las mujeres Fin al feminicidio.” February.

Lynch, B., M. Mallow, K. E. S. Bodde, D. Castaldi-Micca, S. Yanow, and M. Nadas. 2022. “Addressing a Crisis in Abortion Access: A Case Study in Advocacy.” Obstet Gynecol 140 (1): 110-114. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004839. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35849467.

Manjoo, Rashida. 2011. Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against Women, its causes and consequences,. United Nations. General Assembly.

McCammon, Sarah, and Nina Totenberg. 2022. “Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, ending right to abortion upheld for decades.” https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1102305878/supreme-court-abortion-roe-v-wade-decision-overturn.

McCarthy, John D, and Mayer N Zald. 1977a. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 82 (6): 1212-1241.

—. 1977b. The Trend of Social Movements in America: Professionalization and Resource Mobilization. United States: General Learning Press.

McCleary, Kelly, and Holly Yan. 2022. “Protests spread across the US after the Supreme Court overturns the constitutional right to abortion.” CNN. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/27/us/supreme-court-overturns-roe-v-wade-monday/index.html.

Meneghel, S. N., and A. P. Portella. 2017. “[Femicides: concepts, types and scenarios].” Cien Saude Colet 22 (9): 3077-3086. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017229.11412017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28954158.

Noticias, CHV. 2019. “«The violator is you»: Congresista de Nueva York viraliza performance de Lastesis y solidariza con chilenas.” CHV Noticias. Last Modified June 12, 2019. Accessed December 12, 2019. https://www.chvnoticias.cl/nacional/el-violador-eres-tu-congresista-nueva-york_20191206/.

Phoenix, Davin L. 2020. The anger gap: How race shapes emotion in politics. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Salganicoff, Alina, and Laurie sobel. 2022. “State Actions to Protect and Expand Access to Abortion Services.” KFF. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/state-actions-to-protect-and-expand-access-to-abortion-services/.

Staggenborg, Suzanne. 2021. Social Movements. Third Edition ed.: Oxford University Press.

Strawn, Kelley D. 2009. “Contemporary Research on Social Movements and Protest in Latin America: Promoting Democracy, Resisting Neoliberalism, and Many Themes in between.” Sociology Compass 3 (4): 644-657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00217.x.

Tarrow, Sidney. 1998. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Third Edition ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Watson, Katy. 2020. “Argentina abortion: Senate approves legalisation in historic decision.” BBC. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-55475036.

Weldon, S. Laurel. 2011. When protest makes policy. United States of Americ: The University of Michigan Press.

Zernike, Kate. 2022. “The New Landscape of the Abortion Fight.” The New York Times. Last Modified December 10, 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www-nytimes-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.nytimes.com/2022/12/10/us/abortion-roe-wade.amp.html.

Editor: Matt Harmon

Image: AS-COA