BY DIANA PARK

On 6 January 2016, North Korean state media broadcast that it was now “a powerful nuclear weapons state ready to detonate [a] self-reliant A-bomb [atomic weapon] and H-bomb [hydrogen, or thermonuclear, weapon] to reliably defend its sovereignty and the dignity of the nation.”[i] Even though initial seismic readings from US intelligence agencies indicated a high unlikelihood that North Korea detonated a thermonuclear weapon, it is known that the country continues to pursue a nuclear weapons program with alarming, unabated resolve.[ii] The long-range rocket launch on 7 February 2016 confirmed North Korea’s willingness to contravene existing United Nations Security Council resolutions against nuclear and ballistic missile technology tests.[iii] Multilateral negotiations have all but halted, and resuming bilateral negotiations with the United States seems nearly impossible.

This article seeks to explain how North Korea continues to elevate its bargaining power by persisting to develop a more survivable and powerful nuclear force. The piece will also identify possible reasons why the United States’ bargaining power has diminished in negotiations with North Korea. Finally, the article will test some of the core assumptions that have influenced US negotiation strategy since the George W. Bush administration, suggesting possible next moves to reshuffle the dynamics that have stagnated progress in negotiations with North Korea.

These recent events help paint a picture of a North Korea that is actively pursuing a nuclear weapons program. Unless presented with international pressure beyond sanctions, it is unlikely North Korea will consider suspension of the program.

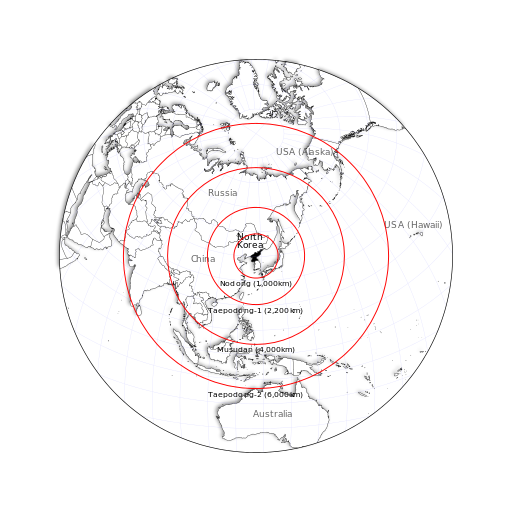

Despite the shock and alarm caused by the recent nuclear test, Kim Jong Un has been steadily and publicly building up various aspects of its nuclear capability. For example, in September 2015 North Korea announced that all aspects of its nuclear program were in operation.[iv] This suggested the country had restarted both its plutonium and enriched uranium programs in order to produce fissile material for nuclear weapons.[v] Additionally, satellite imagery from early December showed that North Korea was digging another tunnel at Punggye-Ri Test Complex, which turned out to be preparations for this latest nuclear test.[vi] Meanwhile, Kim seeks to improve the survivability and range of the North’s ballistic missile capabilities to include the development of a submarine-launched system. Furthermore, a future test launch of the road-mobile KN-08 intercontinental missile will be another significant step forward in the North’s attempt to improve the survivability of its long-range nuclear deployment capabilities (see Figure 1).[vii]

Figure 1.

“Strategic Patience” and Its Failures

Hope for North Korean denuclearization occurred during 2012’s Leap Day “deal,” where North Korea indicated possible agreement to the pre-steps of a moratorium on nuclear activity, agreeing to suspend activities at the Yongbyon uranium enrichment plant.[ix] Immediately after, however, problems began to surface. First, their official statement following the deal failed to include any mention of disabling reprocessing activity. To make matters worse, North Korea conducted a space launch only months after the Leap Day talks. This demonstrated a clear disagreement with the United States as North Korea insisted that a space launch did not constitute a “missile test.”[x]

Since this diplomatic failure, President Obama has chosen to employ a policy of “strategic patience” toward North Korea. The approach enforces broad unilateral and multilateral sanctions (including three imposed by United Nations Security Council resolutions), as well as targeted sanctions enforced through numerous US agencies and offices.[xi] His plan was based on the rationale that cracking down on the finances of North Korea’s elite, while also frustrating the North’s ability to import materials for its centrifuge and weapons program, would influence the North to come back to the table.

Despite these measures, Kim Jong Un has been steadily expanding and improving his efforts to produce fissile material, build longer range ballistic missile capabilities, test more sophisticated nuclear weapons, and increase nuclear survivability through the development of underwater and land-mobile delivery systems.[xii] The country now possesses centrifuge cascades that could generate at least fourteen nuclear weapons by the end of 2016, assuming North Korea is not engaging in any plutonium production.[xiii] However, activity at the 5 MWe reactor in Yongbyon suggests North Korea could indeed be producing plutonium, meaning an increase in nuclear weapons by the end of this year.[xiv] The latest nuclear test reveals an embarrassing final piece of evidence that the Obama administration’s approach lacks teeth when it comes to deterring North Korea’s behavior.

In addition to “strategic patience,” another characteristic of the Obama administration is its refusal to hold bilateral talks with North Korea until the country suspends all nuclear activities. While the Bush administration offered a combination of carrots and sticks, including fuel and food aid, the North still pursued a full nuclear weapons program and abandoned any progress made during the Six Party Talks.[xv] Toward the latter stages of the Six Party Talks in 2009, with almost a dramatic flair, North Korea test fired a Taepodong-2 intermediate range ballistic missile (IRBM), conducted a nuclear test, withdrew from the talks, and claimed that it possessed uranium enrichment capabilities and would use the fuel for a light water reactor.[xvi] Therefore, after such a blatant loss of credibility, preconditions or “pre-steps” became all the more necessary for the Obama administration.

Many experts believe that cooperation with China remains the best and only option to exert pressure on North Korea.[xvii] However, this option is lacking, as China has been slowest to sign onto sanctions with North Korea. As a result, China gave North Korea a lifeline to survive sanctions throughout the past decade. US efforts to impose crippling sanctions are only frustrated by China’s lack of commitment to actually enforce them. China’s priorities with regards to North Korea are misaligned with that of the United States and its allies, whose primary concern is the threat of North Korean nuclear weapons themselves. By contrast, China continues to prioritize its efforts to reduce the risk of North Korea’s economic collapse. A failed state at China’s borders raises concerns of a potential refugee flow that would strain state resources and significantly impact China’s economy. As a result, much of North Korea’s illicit trade, including the trade that feeds its nuclear program via dual use technology, has passed through the land border with China (see Image 1). Therefore, it is counterproductive to keep pursuing a policy that depends on China as a key partner on the denuclearization of North Korea.

Image 1.

Note: Trucks wait for the border crossing at Quanhe and Wonjong to open. Much of North Korea’s illicit dual-use trade supporting its nuclear program passes through the land border with China. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)[xviii]

After North Korea’s nuclear test, the United States must make decisive changes to its diplomatic strategy with the country. In addition to reevaluating its reliance on China, a new diplomatic approach should reconsider the United States’ current strategy for handling North Korea. We cannot ignore the effectiveness of military pressure during initial diplomatic efforts; in the 1990s, a military option was not left off of the table, and North Korea understood the threat.[xix] Since then, the region has become accustomed to scheduled large-scale, biannual military exercises. While these drills are still provocative to North Korea, they are no longer effectively used in concert with other diplomatic maneuvers to create the mounting and worrisome pressure that Exercise Team Spirit once brought to Kim Il Sung. These exercises have become too routine, when military power demonstrations could actually be utilized as a very important diplomatic tool in delivering pressure to North Korea when other options, including sanctions, seem to have lost their effectiveness.

Options for 2016

Obama still has several options in the final year of his presidency. He could leave the situation as is, allowing North Korea to continue to produce fissile material, pursue missile tests, and potentially conduct another nuclear test. Because the recent nuclear test and rocket launch were conducted after copious prior warnings to the international community, we cannot dismiss the possibility that North Korea has orchestrated both the warnings and actions as part of a bargaining chip in its greater negotiations strategy. By conducting the test and rocket launch, North Korea brought the issue of its nuclear weapons back on the foreign policy agenda during the final months of Obama’s second term. However, Obama may have something to gain by doing nothing, in an effort to provide the next president with a fresh start on North Korea. Additionally, if Obama decides to engage in multilateral negotiations efforts, he must also accept the political risk of engaging in formal negotiations. This late in his presidency, reversing his tough stance on preconditions is unlikely to suspend North Korea’s nuclear program. Such a move would be politically risky, and it is improbable that Obama will pursue it at this juncture of his presidency. If Obama does pursue a different course of action, he should look for alternatives to his administration’s current assumptions and strategies.

The first major change should be to challenge the assumption that China still carries the ability to influence North Korea. China has not provided the cooperation and effort necessary to effectively sanction North Korea. Whether due to competing motivations, such as fear of economic collapse in a neighbor country, or else a true lack of sanctioning capabilities, China is not the pivotal partner the United States needs to accomplish denuclearization objectives in North Korea. Unless China is willing to fully cooperate in the multilateral efforts to sanction North Korea, the country cannot be considered a key partner. Secretary of State John Kerry’s comments on China immediately following the January 2016 nuclear tests indicated that the United States is exerting more public pressure on China regarding its policy on North Korea sanctions; this should continue until China truly is willing to help enforce sanctions.[xx]

Second, if Obama were to engage in talks with North Korea, he would have to reassess the US precedent of allocating too few resources to the negotiations, including a lack of high-level involvement.[xxi] While other countries have sent their highest-ranking government representatives to the Six Party Talks, the United States had not followed the same protocol. The United States sent an assistant secretary of state, while China and other countries sent vice foreign ministers or the equivalent. Appointing high-ranking officials to head the negotiations process will signal the United States’ resolve and commitment to addressing the North Korea nuclear problem.

Finally, Obama must rely on the United States’ strengths in the region, particularly alliances with South Korea and Japan. The two countries recently came to a resolution on the issue of comfort women issue, mending historical animosity stemming from the enslavement of Korean girls for service as sex workers for the Japanese imperial army. This signals greater potential for harnessing the trilateral security alliance in an effort to pressure on North Korea. For example, military cooperation, such as intelligence sharing and the ballistic missile defense burden, can mitigate the effects of North Korea’s continued nuclear advances. In the days following North Korea’s latest nuclear test, the three countries issued statements that they “agreed to work together to forge a united and strong international response to North Korea’s latest reckless behavior.”[xxii] The growing strength of Japan-South Korean ties could lead to greater cooperation with respect to their shared interests in denuclearization of North Korea, as well as other intermediary actions such as shared ballistic missile defense capabilities. This trilateral response is a promising start toward a new policy that can utilize the United States’ biggest asset in the region to tackle the mounting nuclear crisis in North Korea.

After graduating from the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, Diana was a James A. Kelly Korea Studies Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, studying nuclear proliferation issues in East Asia. She hopes to pursue a career in international negotiations with a focus on security and nonproliferation.

Dedication:

I would like to dedicate this article to the late Ambassador Stephen Warren Bosworth, a distinguished diplomat and former US Special Representative for North Korea Policy from 2009 to 2011. He graciously provided invaluable insight and mentorship for this article, while also being an example of strength and indefatigable optimism for us all.

Cover Image Credit: (Stephan), Flickr with Creative Commons License.

[i] Jason, Hanna, Tim Hume, and James Griffiths, “North Korea claims it has H-bomb as U.N. discusses human rights abuses,” CNN, 12 December 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/10/asia/north-korea-thermonuclear-claim/

[ii] Karen DeYoung, and Anna Fifield, “Global Powers Condemn North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Test,” The Washington Post, 6 January 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/north-korea-says-it-has-conducted-a-successful-hydrogen-bomb-test/2016/01/06/9add0e52-b436-11e5-a76a-0b5145e8679a_story.html

[iii] Michael Elleman, “North Korea Launches Another Large Rocket: Consequences and Options,” 38 North, US-Korea Institute at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, 10 February 2016. http://38north.org/2016/02/melleman021016/

[iv] Justin McCurry. “North Korea says it has restarted all its nuclear bomb fuel plants,” The Guardian, 15 September 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/15/north-korea-says-it-will-restart-all-its-nuclear-bomb-fuel-plants

[v] Julian Borger, “North Korea’s renewed nuclear threat keeps experts guessing,” The Guardian, 15 September 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/15/north-koreas-renewed-nuclear-threat-keeps-experts-guessing

[vi] Jeffrey Lewis, “New Nuclear Test Tunnel Under Construction at North Korea’s Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site,” 38 North, US-Korea Institute at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, 2 December 2015. http://38north.org/2015/12/punggye120215/

[vii] Sam LaGrone, “NORAD Chief: North Korea Has Ability to Reach U.S. With Nuclear Warhead on Mobile ICBM,” U.S. Naval Institute, 7 April 2015. http://news.usni.org/2015/04/07/norad-chief-north-korea-has-ability-to-reach-u-s-with-nuclear-warhead-on-mobile-icbm

[viii] Figure 1: Jason Davies, “North Korean Missile Ranges,” Wikimedia Commons, 11 April 2013. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North-korean-missile-ranges.svg

[ix] Mark Fitzpatrick, “Leap Day in North Korea,” Foreign Policy, 29 February 2015. http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/02/29/leap-day-in-north-korea/

[x] Jeffrey Lewis, “Rockets and the Leap Day Deal,” Arms Control Wonk, 23 March 2012. http://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/205098/rockets-and-the-leap-day-deal/

[xi] “North Korea,” Sanctions Wiki, 19 December 2016. http://www.sanctionswiki.org/North_Korea Print.:ington Quarterlyoductiorty.” Response Over North Korea’uction Complex.est stakeholders in the region ssible inroad towar Print.:ington Quarterlyoductiorty.” Response Over North Korea’uction Complex.est stakeholders in the region ssible inroad towar

[xii] Mitchel Wallerstein, “Ignoring North Korea’s Nuclear Threat Could Prove to Be a Dangerous Mistake,” The Washington Post, 18 December 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-price-of-inattention-to-north-korea/2015/12/18/a3eb5308-9d3b-11e5-8728-1af6af208198_story.html

[xiii] David Albright and Christina Walrond, “North Korea’s Estimated Stocks of

Plutonium and Weapon-Grade Uranium,” Institute for Science and International Security, 16 August 2012, pp. 27-28. http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/dprk_fissile_material_production_16Aug2012.pdf

[xiv] Print.:ington Quarterlyoductiorty.” Response Over North Korea’uction Complex.est stakeholders in the region ssible inroad towarAlbright and Walrond, “North Korea’s Estimated Stocks of Plutonium and Weapon-Grade Uranium,” Institute for Science and International Security, 16 August 2012. http://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/dprk_fissile_material_production_16Aug2012.pdfhhe two countries recently addressed and resolved the y real risk of meeting bargaining chip in its greater negotiations strateg

[xv] “The Six-Party Talks at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, Arms Control Association, May 2012. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/6partytalks

[xvi] “The Six-Party Talks at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, Arms Control Association, May 2012. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/6partytalks

[xvii] Mitchel Wallerstein, “Ignoring North Korea’s nuclear threat could prove to be a dangerous mistake,” The Washington Post, 18 December 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-price-of-inattention-to-north-korea/2015/12/18/a3eb5308-9d3b-11e5-8728-1af6af208198_story.html

[xviii] Image 1: “Quanhe-Wonjong border,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Queue_-_Quanhe-Wonjong_border_(8553126270).jpg.

[xix] Don Oberdorfer and Robert Carlin, The Two Koreas (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 61.

[xx] Laura Koran and Elise Labott, “John Kerry: China’s Approach to North Korea Hasn’t Worked,” CNN, 7 January 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/01/07/politics/john-kerry-china-north-korea-nuclear-test/

[xxi] John Park, “Inside Multilateralism: The Six-Party Talks,” The Washington Quarterly 28.4 (2005): pp. 75-91.

[xxii] Foster Klug and Hyung-Jin Kim. “US, South Korea and Japan Vow Strong Response Over North Korea’s Claimed Hydrogen Bomb Test,” U. S. News and World Report, 6 January 2016. http://bigstory.ap.org/article/4d04706418e6460594e2dabea17cbffa/n-korea-says-it-conducts-successful-powerful-h-bomb-test