“We don’t go anywhere or do anything without the National Guard. We can’t do what we do as an Army without the National Guard. Every time we have asked, the National Guard has been ‘Always Ready, Always There.’” – General James C. McConville, August 27, 20221

“There’s no sugarcoating it: all three components of the Army missed their required end strength for fiscal 2022, leaving boots unfilled after missing recruiting goals…” – Army Times, October 10, 20222

Six months before COVID-19 shuttered the nation, the United States Army published its first “Army People Strategy.”3 Gen. James McConville, the service’s senior military leader, intended the document to serve as a roadmap to “drive success in our Readiness, Modernization, and Reform priorities.”4 No one imagined that just three years later, McConville’s now familiar tagline “People First. Winning Matters.” would reveal a completely different concern.

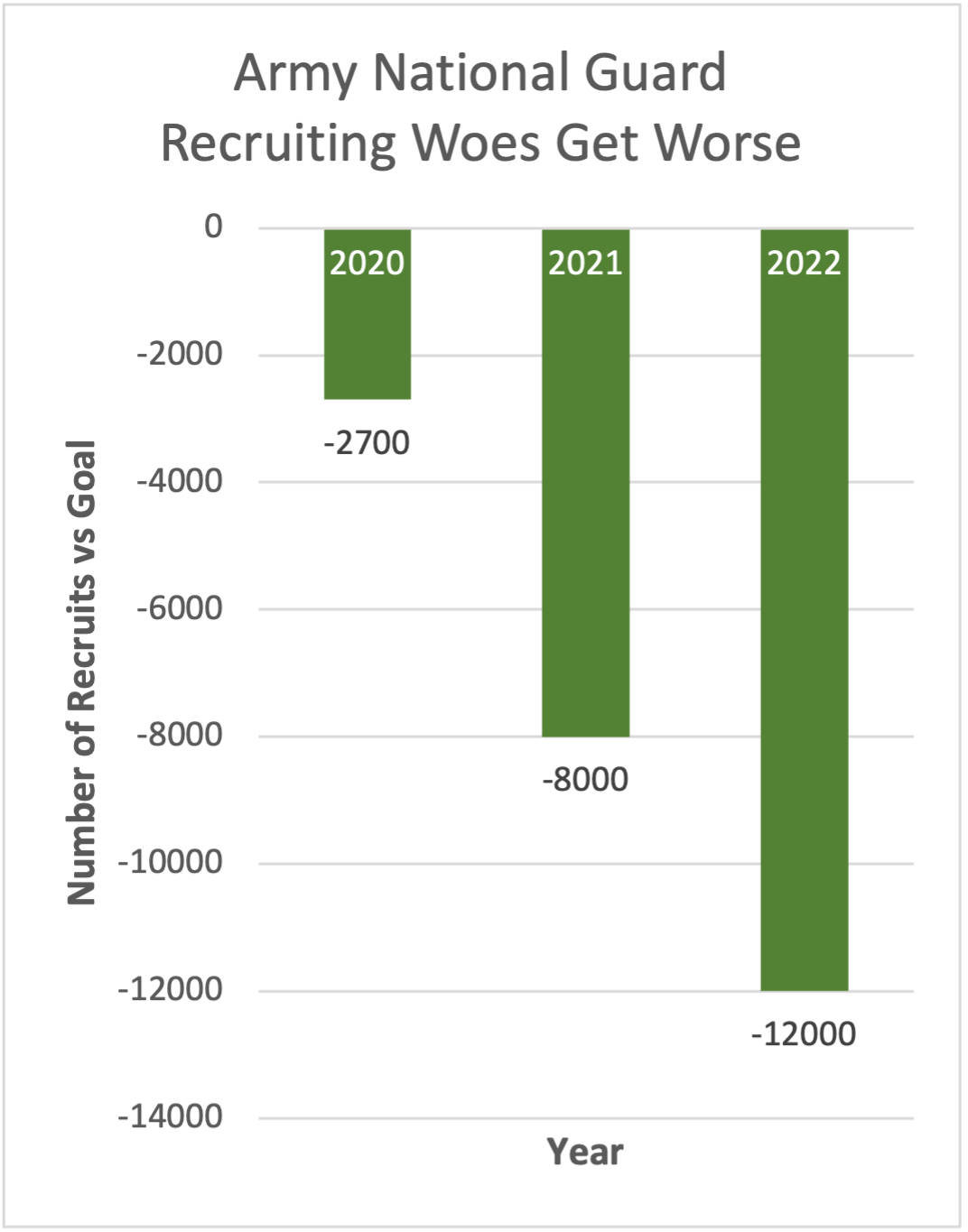

Fewer new recruits than expected joined the service in each of the past three fiscal years (2020-2022).5 Despite withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan, demands on the US Army remain high. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, competition with China in the Pacific, and maintaining relationships with allies and partners require forward presence; in other words, soldiers deployed overseas. The Army will be challenged to maintain forward presence if its recruiting failures remain unaddressed.

Recruiting woes disproportionately affected the Army National Guard (ARNG), the service’s largest reserve component, which missed its targets by increasing margins.6, 7, 8 The Army National Guard fulfills significant national security objectives, including maintaining military-to-military relationships with 100 allied and partner countries and providing critical capabilities for Army multi-domain operations.9 Since 2001, its role in defending vital national interests has dramatically evolved. Its recruiting methods have not.

To improve recruiting effectiveness, the Army National Guard needs to reconsider its recruiter employment and development practices. Before assuming recruiter roles, most ARNG soldiers spend a decade learning how to apply combat power under austere conditions. Leadership aside, few skills transfer between the application of force to dominate an adversary and guidance counseling for uncertain young adults – the largest proportion of new members who join the organization. The ARNG must ask itself: Are mid-career soldiers the best candidates to recruit a new generation of recruits?

Recruiter training also deserves scrutiny. The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated less effective virtual training than the customary six-week in-person recruiter instruction.10 Continuity between personnel leaving and assuming recruiting duties also suffered because of remote work requirements. These unfortunate realities exacerbated the strain on already brief tours of duty. The average recruiter only serves in the position for 1.6 years.11

To their credit, many ARNG recruiters learned valuable lessons during the pandemic. Embracing instant messaging, creating social media content, and leveraging recruit-to-recruit networks yielded desperately needed dividends.12 Yet, few of these skills are taught in formal recruiter instruction. The ARNG must also ask: Is the current recruiter development model sufficient to enable recruiter success today?

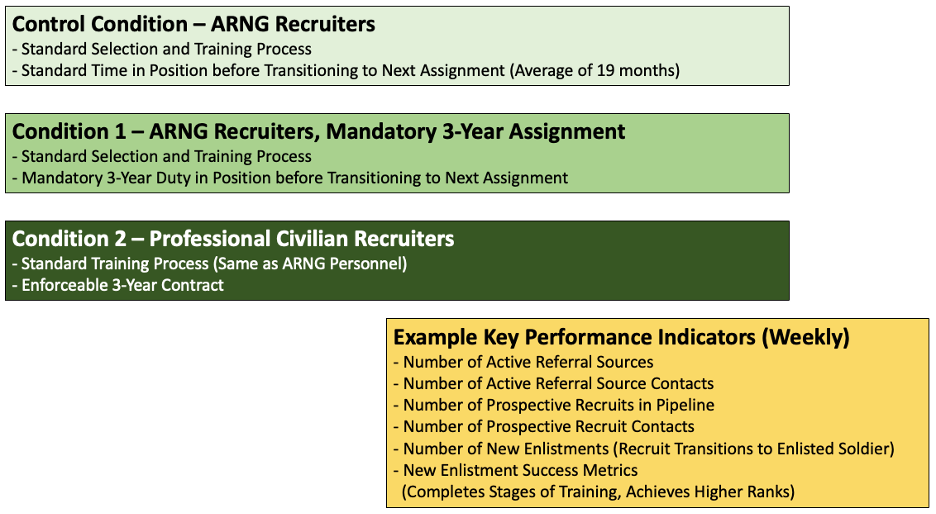

To answer these questions, the ARNG should conduct a pilot program comparing soldier recruiters to professional civilian recruiters. Civilian recruiters should receive the same administrative training as new ARNG recruiters to ensure equal knowledge of eligibility criteria, information technology systems, and enlistment procedures. Then, each group should be placed in comparable urban markets with sizable populations for a minimum of three years. At periodic intervals, they should be compared to their counterparts working in demographically similar cities. Comparisons should include uniformed ARNG recruiters operating under the current system (not participating in the pilot), uniformed ARNG recruiters operating under the three-year pilot program, and civilian recruiters operating under the pilot program.

This experiment will help the ARNG better understand:

- How important is first-hand experience as a service member to recruiter success?

- How do training and prior experience impact recruiter effectiveness during the first year of assignment?

- How does tenure in the role impact recruiter effectiveness after the first year?

- How does tenure in the market impact recruiter effectiveness?

- What behaviors and practices between the groups (uniformed military and non-uniformed civilian recruiters) affect results?

Quantitative measures of effectiveness should include the number of recruits who join the organization, the effectiveness of each recruiter, and expense per recruit acquired. Qualitative comparisons should track new recruits through basic combat training, advanced individual training, and first duty assignments to determine differences in performance and job satisfaction.

Recruiting efforts appear to be rebounding thanks, in part, to relaxed COVID-19 mitigation efforts.13 This is good news. Still, the percentage of Americans able and willing to serve continues to decline.14, 15 The organization must find new and better ways to meet growing requirements.

Heightened geopolitical tensions in Eastern Europe and the Pacific, illegal immigration, the destructive effects of climate change, and passionate public discourse concerning equity and justice will require engagement from America’s citizen-soldiers for the foreseeable future. The Army National Guard must experiment and adapt its recruiting practices to meet these challenges. To win when it matters, we need people first.

Photo credit: Benjamin Faust via Unsplash

[1] Jim Greenhill, “McConville: ‘We Can’t Do What We Do as an Army without the National Guard,’” www.army.mil, August 28, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/259724/mcconville_we_cant_do_what_we_do_as_an_army_without_the_national_guard.

[2] Davis Winkie, “An End Strength Crisis Is Here for the Army,” Army Times, October 10, 2022, https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2022/10/10/an-end-strength-crisis-is-here-for-the-army/.

[3] “The Army People Strategy,” October 2019, https://www.army.mil/e2/downloads/rv7/the_army_people_strategy_2019_10_11_signed_final.pdf.

[4] “The Army People Strategy,” 2.

[5] “Facts and Figures,” U.S. Army Recruiting Command, accessed December 2, 2022, https://recruiting.army.mil/pao/facts_figures/.

[6] Jon Soucy, “Army National Guard Exceeds Strength Goals for Fiscal Year,” NationalGuard.mil, October 27, 2020, https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/Article/2396010/army-national-guard-exceeds-strength-goals-for-fiscal-year/.

[7] Ellie Kaufman, “US Military Struggled to Attract National Guard and Reserve Troops but Met Targets for Full-Time Recruits in 2021 Fiscal Year,” CNN Politics, January 18, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/14/politics/military-recruitment-numbers-2021/index.html.

[8] Rob Lt. Col. Perino, “Army National Guard Prepares for 2030,” www.army.mil, October 17, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/261185/army_national_guard_prepares_for_2030.

[9] Erich B. Smith, “Guard’s Global Reach, Capabilities Support National Defense Strategy,” www.army.mil, December 5, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/262521/guards_global_reach_capabilities_support_national_defense_strategy.

[10] Venessa Grambusch and Olisa Powell, “Recruit the Recruiter Briefing,” accessed December 3, 2022.

[11] Soucy, “Army National Guard Exceeds Strength Goals for Fiscal Year.”

[12] Will Martin, “War for Talent: Army Guard Recruiters Find Success in Social Media,” Reserve & National Guard (blog), October 3, 2022, https://reservenationalguard.com/recruiting-and-retention/war-for-talent-army-guard-recruiters-find-success-in-social-media/.

[13] “Multiple Factors Helping Boost Guard Recruiting | National Guard Association of the United States,” February 14, 2023, https://www.ngaus.org/newsroom/multiple-factors-helping-boost-guard-recruiting.

[14] Thomas Novelly, “Even More Young Americans Are Unfit to Serve, a New Study Finds. Here’s Why,” Military.com, September 28, 2022, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2022/09/28/new-pentagon-study-shows-77-of-young-americans-are-ineligible-military-service.html.

[15] Matt Seyler, “Military Struggling to Find New Troops as Fewer Young Americans Willing or Able to Serve,” ABC News, July 2, 2022, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/military-struggling-find-troops-fewer-young-americans-serve/story?id=86067103.