In The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas, Le Guin (1973) describes a fictional city of Omelas where people live in happiness and prosperity except for one secret they share – there is a child locked in a basement, and the city’s continued success is contingent on the perpetual misery of this child. Free the child and the city’s success disappears. Most of Omelas’ people accept this dark secret guaranteeing their happiness, while others who cannot bear it walk away.

Omelas could be a metaphor for Singapore. From the outside, Singapore is lauded on its economic transformation from third world to first within a span of five decades. Today, it holds the 10th highest GDP per capita globally (World Bank, 2017a), consistently topping international rankings in terms of being one of the best places to do business (World Bank, 2017b). Ranked as the best place to live in Asia, Singapore boasts of having the best city infrastructure (Mercer, 2017) and education system (OECD, 2016).

Many argue that Singapore’s sustained periods of high growth and structural transformation were built on hard choices made by the government regarding economics and politics. However, the costs of these choices are less well studied. Despite Singapore’s remarkable economic progress and high living standards, emerging costs in the form of inequality and social issues have begun to raise questions about the current growth paradigm.

Has Growth Been Inclusive?

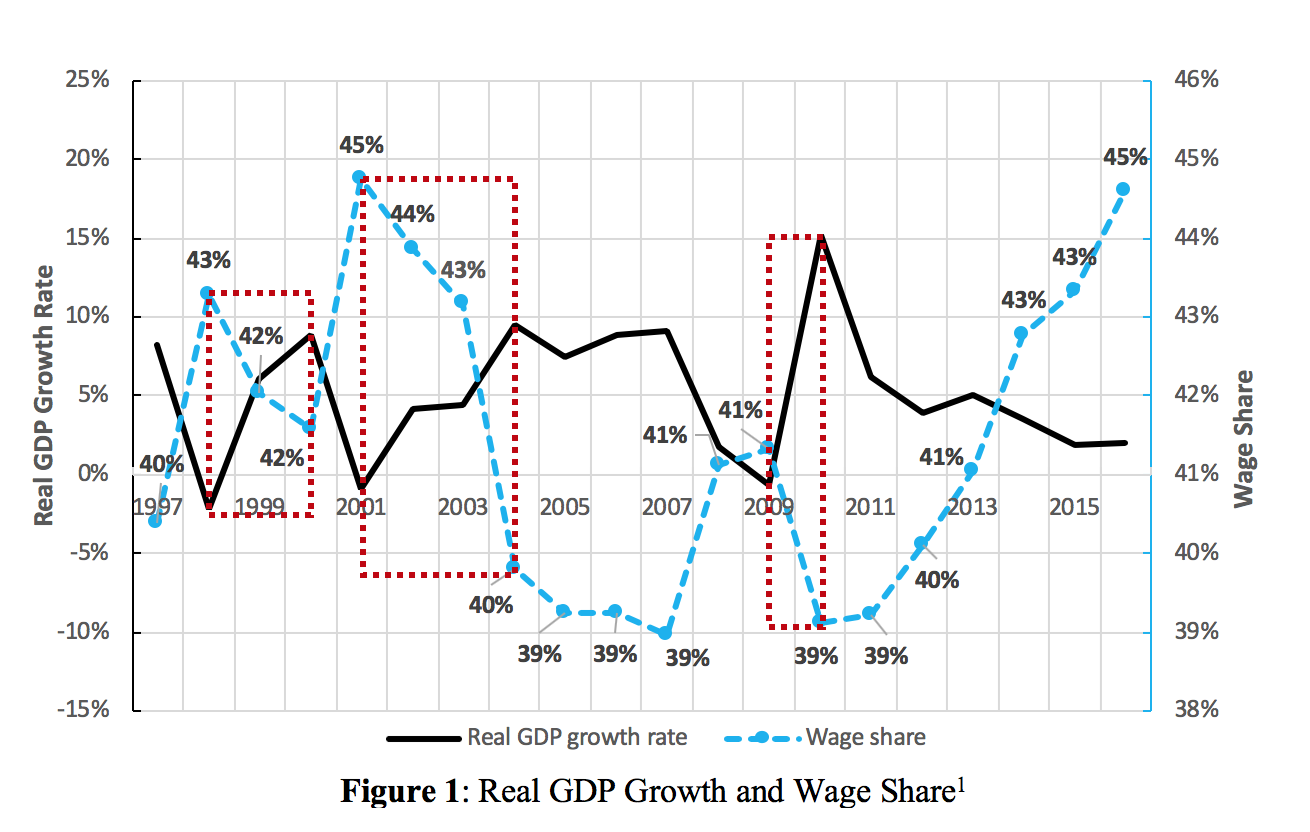

An examination of income inequality indicators shows that the level and pace at which inequality has grown in Singapore has been significant. While Singapore’s wage share of GDP has increased in the last two decades, its wage share of 45 percent in 2016 remains low compared to the average of 62 percent in other advanced economies (ILO and OECD, 2015). Periods of strong growth have been associated with falling wage share. In the periods of 1998-2000, 2001-2004, and 2009-2010 where GDP grew rapidly (marked out in Figure 1), this corresponded with declines in wage share of 3.9 percent, 11.1 percent, and 5.4 percent respectively.

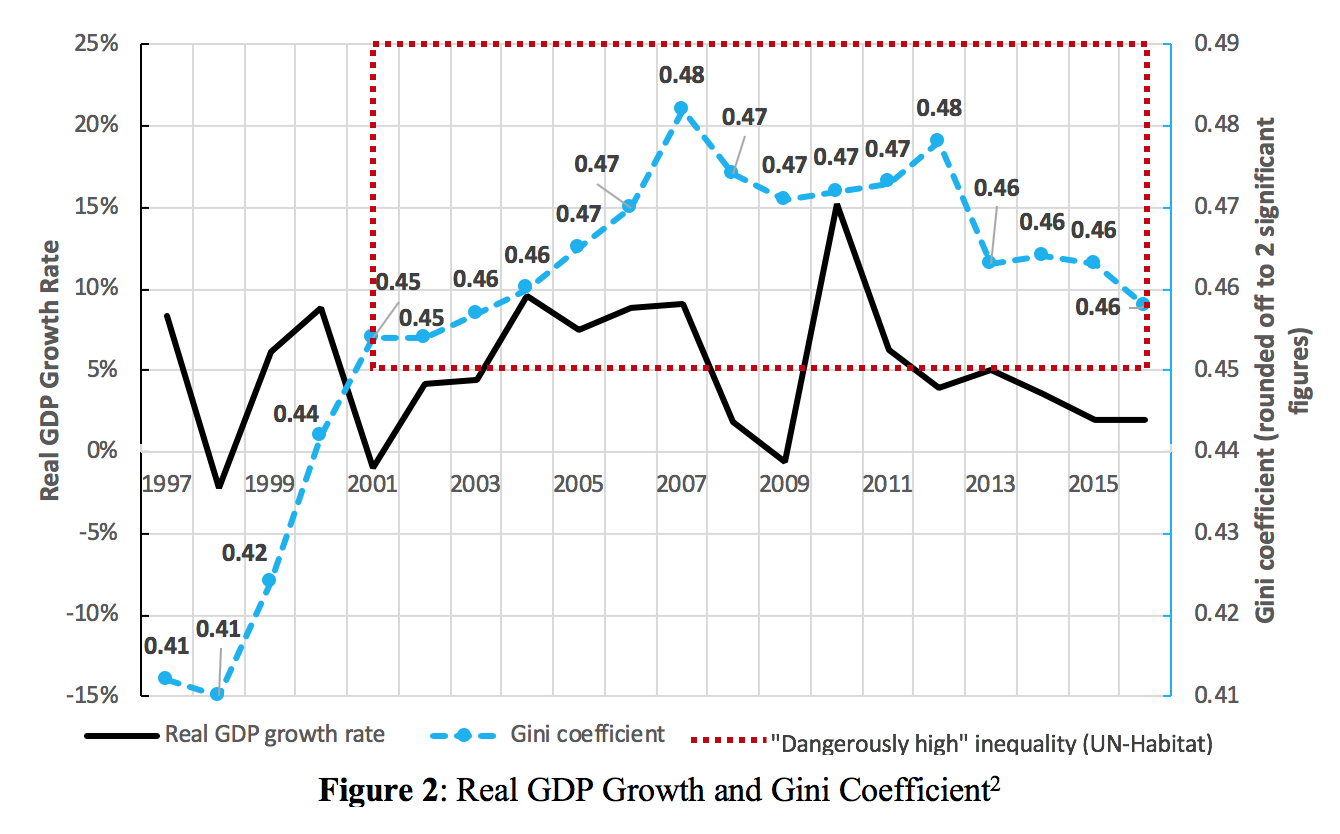

Singapore’s Gini coefficient has seen a marked increase from 0.412 in 1997 to 0.458 in 2016 as shown in Figure 2. Its Gini coefficient range of 0.410 to 0.482 lies well above the UN-Habitat’s (2008) International Alert Line for Income Inequality of 0.4. Although there has been a decline in recent years since 2012, it has remained in the “dangerously high” range of 0.45 to 0.49 since 2001 according to UN-Habitat standards, which warn countries of potential losses in investment and social unrest should remedial actions not be undertaken.

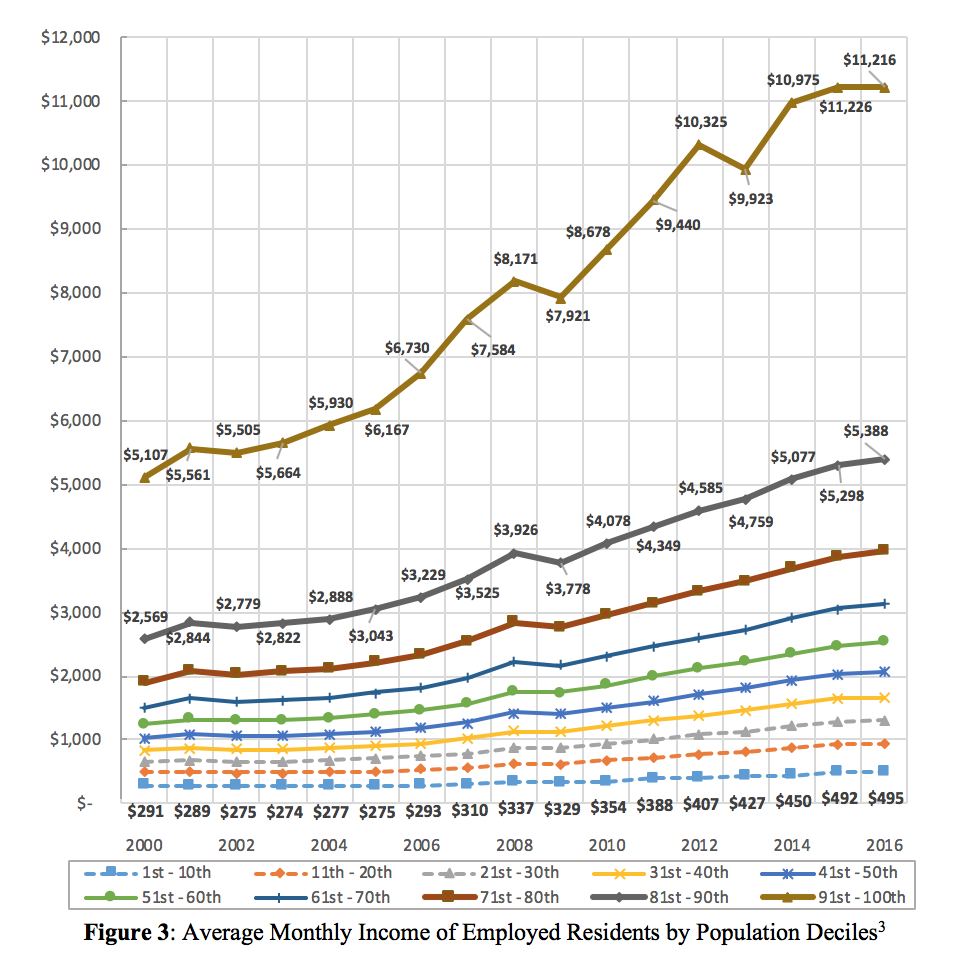

Growth of monthly average incomes of employed residents from the lowest population decile pale in comparison to the rapid rise in wage growth of the 91st to 100th decile as illustrated in Figure 3. Average wages of the top decile saw a growth rate of 120 percent from 2000 to 2016, almost double that of the lowest decile of 70 percent. The income gap between the top decile and the rest of the population has widened markedly over the same period. Among developed countries, the wage disparity between those in the top and bottom segments in Singapore was identified as the largest (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010).

To What Extent Has Growth Improved Societal Wellbeing?

An evaluation of Singapore’s societal wellbeing along the dimensions of healthcare, familial relations, and individual wellbeing finds that overall wellbeing levels in recent years have not been commensurate with its economic achievements. Regarding healthcare, life expectancy and the proportion of elderly have increased while the old-age support ratio has fallen from 9.0 in 2000 to 5.4 in 2016 (Department of Statistics, 2017), intensifying strains on the working population. Studies show that the provision of care services and facilities has not kept pace with rising healthcare demands arising from population aging and increased prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity (Lim, 2013). Singapore’s proportions of public health expenditure relative to GDP – ranging from 0.9 percent to 2.1 percent from 2000 to 2014 – are much lower compared to the OECD average of 8.9 percent (OECD, 2015; WHO, 2017). Coupled with rising healthcare costs, this creates new barriers to healthcare access which disproportionately disadvantages the poor.

In terms of familial relations, the trend of declining marriages and increasing divorces has persisted over the last two decades while the median age of first marriages rose. Total fertility rates have continued to fall, from 1.6 in 1997 to a low of 1.2 in 2016 (Department of Statistics, 2017). Surveys conducted by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (2015) and National Family Council (2016) found a growing proportion of Singaporeans expressing that long working hours have impeded them from spending desired time with their families. Among married respondents, the number attesting to being satisfied with their marriages fell. Issues of family violence appear to be on the rise, with the number of domestic abuse cases nearly doubling from 2012 to 2016 (Tan, 2016). This suggests that despite overall increases in household income, the institutions of marriage and family appear to be deteriorating.

On individual wellbeing, a cross-country survey found Singapore ranking the lowest in terms of job satisfaction, with senior executives emerging as the unhappiest (Chua, 2016). With average annual working hours of 2,371 in 2016 – exceeding that of other East Asian economies such as Korea (2,113) and Japan (1,719) – Singaporeans face the longest working hours globally (Ministry of Manpower, 2017; OECD, 2017). In this context of rising dissatisfaction, the number of mental health related issues have grown. Suicide rates increased by 23 percent from 2000 to 2016 (Samaritans of Singapore, 2017). Mental health disorders are on the rise, with the Institute of Mental Health reporting an average increase of seven percent in the number of new patients annually (Chia, 2016). Singapore is found to hold the lowest levels of social trust among developed countries (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010). These indicate that while living standards have improved through increased employment opportunities, new forms of mental distress and social distrust have emerged due to increased competition stimulated by the emphasis on growth and productivity.

What are the Implications?

Like Omelas, Singapore’s development over the past five decades has been underpinned by a social compact forged through the state’s early accomplishments in facilitating its economic transformation and delivering world-class public infrastructure and services. This allowed the state to promote the rhetoric asserted by its first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in 1974 that “growth must come before sharing” (Pang, 1975, p.15). However, this social compact has not seen its initial achievement of equitable growth continuing into recent decades, raising the question of whether the time has come for sharing to claim equal, if not greater, priority as that of growth.

There are significant implications. First, there is a need to acknowledge the severity of inequality in terms of the extent and pace at which it has grown in Singapore. Second, it calls for a greater alignment of Singapore’s economic and social policies given that strong growth has not corresponded with commensurate improvements in societal wellbeing. Third, it underlines the urgency of fundamentally re-examining the paradigm of growth over equity. These implications hold not only for Singapore’s future development but are also noteworthy for other developmental states facing similar socioeconomic dilemmas and developing countries aspiring to Singapore as a model.

The recent decline and consistent depression of the Gini coefficient after factoring in government taxes and transfers show that state efforts to address these issues are making headway, which are commendable. However, more needs to be done. Whether Singapore’s hard-earned economic growth and social stability can be sustained moving forward will ultimately depend on the extent and commitment with which it adopts a deliberate, concerted approach to continually recalibrate and redesign its economic and social strategies to meet evolving needs.

Her full thesis, The Hidden Costs of a Successful Developmental State: Prosperity and Paucity in Singapore can be accessed here.

Works Cited

Chia, L., 2016. The Stigma of Depression: Those Who Suffer in Silence [online]. Singapore: Channel News Asia. Available at: http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/the-stigma-of-depression-those-who- suffer-in-silence-8044448 [Accessed: 10 August 2017].

Chua, A., 2016. Singapore Workers Unhappiest in South-east Asia: Survey [online]. Singapore: Today Online. Available at: http://www.todayonline.com/singapore/singapore-workers-unhappiest-southeast-asia- survey [Accessed: 10 August 2017].

Department of Statistics, 2017. SingStat Table Builder, Selected Economy and Population Statistics [online]. Singapore: Department of Statistics. Available at: http://www.tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/publicfacing/mainMenu.action [Accessed: 5 August 2017].

International Labour Office (ILO) and OECD, 2015. The Labour Share in G20 Economies. Turkey: International Labour Organisation and OECD.

Le Guin, U., 1973. The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. Creative Education, Inc.

Lim, J., 2013. Myth or Magic: The Singapore Healthcare System. Singapore: Select Publishing.

Mercer, 2017. Quality of Living City Rankings [online]. Available at: https://mobilityexchange.mercer.com/Insights/quality-of-living-rankings [Accessed: 10 August 2017].

Ministry of Manpower, 2017. Summary Table: Hours Worked [online]. Singapore: Ministry of Manpower. Available at: http://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Hours-Worked- Summary-Table.aspx [Accessed: 12 August 2017].

Ministry of Social and Family Development, 2015. Survey on the Social Attitudes of Singaporeans. Singapore: Ministry of Social and Family Development.

National Family Council, 2016. Families for Life Survey 2016. Singapore: National Family Council.

OECD, 2015. OECD Health Statistics 2015. Focus on Health Spending [online]. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Focus-Health-Spending-2015.pdf [Accessed: 10 August 2017].

OECD, 2016. PISA 2015: Results in Focus [Online]. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-2015- results-in-focus.pdf [Accessed: 5 June 2017].

OECD, 2017. Hours Worked (Indicator) [online]. OECD. Available at: https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm [Accessed: 12 August 2017].

Pang, E. F., 1975. Growth, Inequality and Race in Singapore. International Lab Review., 111, p.15.

Samaritans of Singapore, 2017. Annual Report 2016/2017. Singapore: Samaritans of Singapore.

Tan, T., 2016. More cases of vulnerable adults being abused by their families [online]. Singapore:

The Straits Times. Available at: http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/more-cases-of-vulnerable-adults-being-abused- by-their-families [Accessed: 12 August 2017].

UN-Habitat, 2008. State of the World’s Cities 2008-2009: Harmonious Cities. Earthscan.

WHO (World Health Organisation), 2017. Global Health Expenditure Database [online]. Available at: http://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/Indicators/en [Accessed: 5 August 2017].

Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, K., 2010. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. Penguin UK.

World Bank, 2017a. World Bank GDP Per Capita Data [online]. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?year_high_desc=true [Accessed: 5 June 2017].

World Bank, 2017b. Doing Business 2017 [online]. Available at: http://www.doingbusiness.org/rankings [Accessed: 5 June 2017].

Image Credit: Pexels