BY SIMON ROWELL

On the night of 10 February 2011, Tahrir Square in central Cairo was seething with people inspired by the prospect of unprecedented political change. Transformed from a busy, dirty transport hub, the square had become an oasis of calm and cleanliness, organized by voluntary systems for recycling, compost, lost-and-found items, and even children’s day care. Inside, political discussions raged openly; outside, the police continued to intimidate demonstrators and onlookers alike. Even under this extreme pressure, “The square and the protestors remained undeniably peaceful,” recalls Maryam Ishani, a digital media journalist based in Cairo.

While the speed of the revolt gave the appearance of a spontaneous uprising, it had actually followed a deliberate strategic plan concocted many years before by a youth organization called the April 6 Movement, along with others. But the April 6 Movement did not work alone. Much of what transpired in Tahrir Square—the takeover of prime public space, the formation of parallel institutions, and even the “clenched first” logo of the April 6 Movement—bore the undeniable hallmarks of CANVAS, an organization devoted to spreading the message of nonviolent resistance. Through a week-long training course in Belgrade a year and a half earlier, CANVAS helped launch ripples felt in waves across Tahrir Square and all of Egypt.

Revolution in Serbia

The peaceful toppling of Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia in 2000 is arguably the most successful recent example of nonviolent resistance. Two college friends from Belgrade, Srdja Popovic and Slobodan Djinovic, were instrumental in forming the OTPOR movement (meaning “resistance” in Serbian), which would galvanize wide-ranging Serbian popular support against the regime. OTPOR developed many innovative tactics for attracting attention and support of the local population, often relying on humor and popular imagery. In one such event, the image of Milosevic was plastered on a barrel in central Belgrade and locals were offered a chance to beat it with a stick, leaving police with the unenviable task of either arresting people for a nonexistent crime or arresting the barrel itself. (They opted to arrest the barrel, to the laughter of onlooking locals.) In another event, the city was brought to a noisy standstill as citizens beat pots and pans on their balconies during the state-run news broadcast to protest the closure of the last independent media outlet. Although they were characterized in the press by a flag sporting a clenched fist, an unwavering commitment to nonviolent resistance remained at the core of their struggle.

OTPOR’s approach was shaped by the work of preeminent nonviolent revolutionary scholar Gene Sharp. Sharp’s seminal works, From Dictatorship to Democracy (2010) and The Politics of Nonviolent Action (1973), describe the theory and history of global nonviolent resistance and provide a list of 198 practical tools of nonviolent action. Years later, Sharp’s treatise on how to destabilize a government’s “pillars of support” is still a core part of CANVAS teachings.

The OTPOR movement was a remarkable success. It united the normally factional populace to stand behind one presidential candidate, Vojislav Kostunica, and it motivated a huge swath of Serbians to mobilize against Milosevic, storm the Parliament, and evict the leader from power. From this experience, Popovic and Djinovic learned that the combination of unity, discipline, and planning could bring down even the most intransigent regime.

Moving Beyond Serbia

With the successful installation of a new democratic regime in Serbia, Popovic and Djinovic took different paths: Djinovic focused on his growing telecommunications business and Popovic was elected to the new Serbian parliament. However, they also began to receive calls from others seeking models for change—most notably from Georgia. Under the brutal regime of Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia was one of the most corrupt countries in the region, and a number of Georgian civil society groups were anxious for change. In early 2003, a number of these activists, including the Tbilisi State University Student Government, visited OTPOR’s leaders to learn how to reform the much-derided electoral system. Nini Gogiberidze, a member of the visiting group, described to me in an e-mail interview how they “talked and talked and talked about helping the Georgians understand the vital structural campaign requirements for success,” but these discussions also broadened their minds to possibilities beyond the initial scope of their intended campaign.

After these conversations, the Georgian resistance took on the name Kmara, meaning “It’s enough.” Upon their return, students began painting road signs with the evocative “Kmara” imprint, eventually building enough intrigue and momentum to result in the first ever Kmara demonstration on 14 April 2003. Djinovic and another OTPOR representative also subsequently visited Georgian training camps multiple times. Gogiberidze recalls the experience. “Srdja and Slobodan provided more than just knowledge; they provided inspiration,” she wrote. “I thought that initially whatever they were telling us was impossible to implement in Georgia . . . but they gave us a much needed wake-up call and allowed us to think of the impossible.”

Only seven months after those initial meetings—and with the familiar clenched fist flying high on white flags—nonviolent protestors, armed only with red roses, stormed the national parliament in response to blatant election fraud. That act led to the eventual toppling of the Shevardnadze regime and the coining of the now familiar term, the “Rose Revolution.”

CANVAS Spreads the Message

In 2004, Popovic and Djinovic established the Centre for Applied NonViolent Action & Strategies (CANVAS) as a way to meet the growing demand for their expertise in nonviolent resistance. The organization was deliberately designed as a nonprofit, nongovernmental, educational institution focused on the use of nonviolent conflict to promote human rights and democracy. At the request of a relevant organization, movement, or group of activists, two CANVAS trainers will conduct a five-day workshop, adjusted to the circumstances of the individual participants. The trainers are usually former activists coming from countries where nonviolent resistance has recently succeeded, including Serbia, Georgia, Lebanon, the Philippines, and South Africa. Within the workshop, participants are empowered to determine the strategies and tactics that will work in their home nations and develop any new tactics that are needed.

The theory behind CANVAS teachings, which aligns strongly with Sharp’s works, is that “power in society comes from the obedience of the people,” as Popovic noted in an e-mail interview I conducted with him. Each individual, with his or her own small source of power, can withdraw that obedience and resist traditional commands. This process, in turn, destabilizes the existing autocratic power structure. Popovic emphasizes that the same ideas of “unity, discipline, and planning” applied in Serbia remain pivotal to the success of any nonviolent resistance. In practice, CANVAS focuses not on operations, but on the overarching strategy and long-term commitment required to wage effective resistance. As Popovic reflects, “There must be a shared vision of tomorrow and a grand strategy for how to attain it.” However, to achieve any lasting success, these movements must be built on a series of small victories.

CANVAS at the Root of Revolution

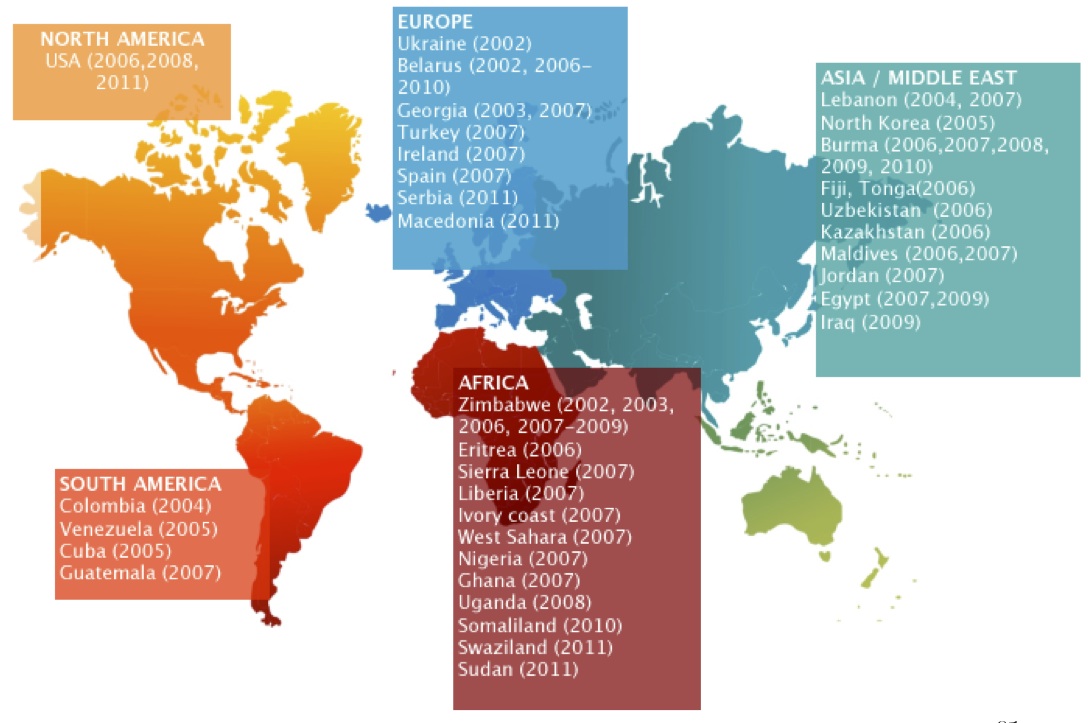

Over the past ten years, CANVAS has conducted 123 workshops in forty-six countries for more than 2,000 participants. It has trained members of the “Pora” movement in Ukraine’s Orange revolution, the “Cedar Revolution” in Lebanon, which through mass sit-ins helped oust Syrian troops after thirty-five years of conflict, and even a pro-democracy opposition group in the Maldives. It also trained Mohammed Adel, one of the leaders of the April 6 Movement, who became one of the most important organizers of the Egyptian uprising focused in Tahrir Square.

Not all trainings have been so successful, however. CANVAS trained a number of Iranian activists involved in the “Green Revolution.” Despite generating significant community investment and practicing nonviolent tactics, the increasingly strict government stymied success. Other trainees in Syria are undergoing a very challenging standoff with the regime in early 2012.

What has changed in these revolutions over the last decade? Popovic explains that there are three main differences between the Eastern European revolutions of the 1990s and the Arab Spring. First, Arab activists are operating in a very narrow political space between oppressive autocratic governments and sometimes-radical Islamic groups. Second, unlike Eastern Europe’s mostly middle-aged population, most Arab countries (with an average age of twenty-four) are built on youth born after the regimes were originally established and are therefore more open to thawing this “politically frozen” region. Third, new media has reshaped nonviolent resistance to the same extent as it has everyday life. It has created alternative media space for democracy activists, enabled the rapid mobilization of activist groups, and allowed everyone to be a reporter. These factors, Popovic revealed, increase the “price tag” of oppression.

As an organization, CANVAS has an almost evangelical zeal in promoting its message of nonviolence and has been busy expanding its repertoire of educational tools. By bringing academics, media outlets, and international organizations into the fold, CANVAS has worked to increase broader awareness about the existence and practice of nonviolent resistance. CANVAS has developed a number of new tools including university curricula on nonviolent struggle, handbooks for activists, and video games, DVDs, and movies and has also developed a course to be taught at Belgrade University. Its position as the dominant force in nonviolent resistance trainings across the world looks set to continue.

The Force for a Nonviolent Future

The world of nonviolent resistance is now expanding rapidly. When I visited the Albert Einstein Institution, the think tank of Gene Sharp, the small office was cluttered with heavily packaged envelopes responding to requests around the world for copies of Sharp’s anthology of nonviolent resistance writings. CANVAS is also overrun with requests and is considering a host of ambitious plans including developing an online training capability. Sharp and Popovic are even recognized among Foreign Policy magazine’s “Top Global Thinkers” (Foreign Policy 2011).

Even with the substantial demand for information on nonviolence, challenges remain. Funding for the work has always been tight, and currently half of CANVAS funds come from donations from Djinovic’s telecommunications business. The workshop model relies on a limited supply of trainers who are veterans of nonviolent revolutions. And, after the jubilation of any successful revolution, beginning the long process of creating new institutions can be frustrating for a people anxious for immediate but fundamental change. Egypt more than any other country embodies these challenges.

While Egypt continues to experience the growing pains of a new democracy, there is little doubt that the country has changed forever since that restless evening of 10 February 2011. Popovic remains modest about the role of CANVAS in recent revolutions: “It is the commitment and courage of the (local) people to freedom that really counts.” But it is because of the tireless and inspired work of groups like CANVAS that the information about the power of nonviolent resistance is accessible to a wide audience. Hoarding power is becoming increasingly difficult for uncompromising dictators across the world.

References

Foreign Policy. 2011. The FP top 100 global thinkers. Foreign Policy, December.

Sharp, Gene. 1973. The politics of nonviolent action. Volumes 1-3. Manchester NH: Extending Horizons Books, Porter Sargent Publisher.

———. 2010. From dictatorship to democracy: A conceptual framework for liberation. 4th edition. Boston: The Albert Einstein Institution.

For More Information

Arrow, Ruaridh. 2011. How to start a revolution. Film directed by Ruaridh Arrow.

This article was originally published in the 2012 edition of the Kennedy School Review.

Simon Rowell is a 2012 Master in Public Administration candidate at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, focusing on business and government policy and international politics. He is a former international corporate lawyer with expertise in emerging markets and a governor of a primary school in London.

Photo source here.

Map of CANVAS activities printed with CANVAS’s consent.