Introduction

The United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that a record-breaking 339 million people will need humanitarian assistance in 2023. Eighty-six million of those people live in countries currently sanctioned by the United Nations—a number that grows to 208 million living under U.S. sanctions. These include internally displaced Venezuelans, civilians living in government-controlled areas of Syria, and innocent bystanders to armed conflict in Sudan.

Measuring the impact of sanctions on these vulnerable groups is highly controversial, intensely politicized, and practically difficult to do.

For example, when the United Nations Security Council sanctioned Iraq in response to the 1990 invasion of Kuwait, there were fierce debates about whether sanctions upheld or undermined human rights. Advocates for sanctions relief were accused of appeasing Saddam Hussein while advocates for tougher sanctions were seen as targeting innocent civilians. Some global health experts estimated that between 100,000 and 227,000 Iraqi children died as a direct result of sanctions, while others have since argued that survey data was inflated by Hussein’s regime and that child mortality was not affected at all. In a now-infamous interview with 60 Minutes, then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said that even if half a million Iraqi children died as a result of sanctions, “the price is worth it.” Thirty years later, there is still no consensus.

Overcompliance

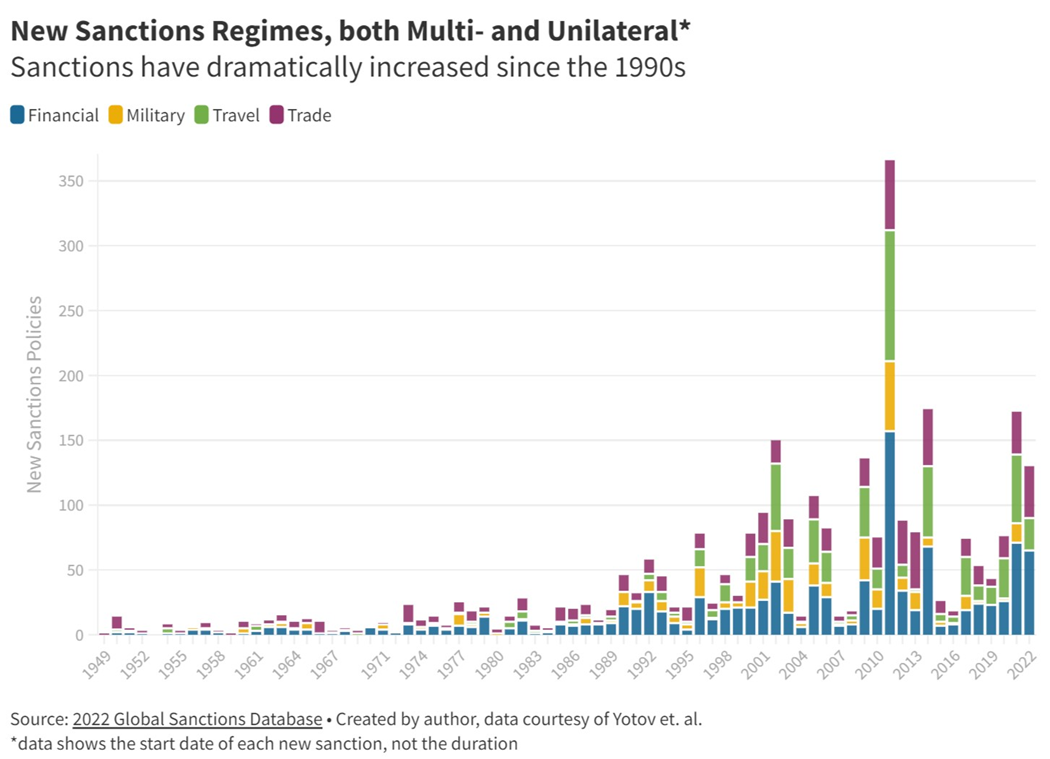

What we do know is that sanctions are not going away any time soon. Sanctions (especially financial sanctions) now form the cornerstone of U.S. policy on major issues such as the war in Ukraine, the rise of the Taliban, and the United States’ trade relationship with China. As the United States relies on financial measures more than ever, it must also analyze the collateral impacts of these sanctions and build robust protections for those in humanitarian distress.

Whereas trade sanctions limit specific products, sectors, or countries from import/export markets, financial sanctions limit bank accounts, money transfers, and assets. These assets and money transfers are the lifeblood of international criminal activity, but they are also necessary for legitimate financial transfers made by nonprofit actors working in humanitarian crises.

Sanctions do already include exemptions for humanitarian goods and services – although there is a wrinkle between policy and practice. Although the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) writes exemptions into its policy so that nonprofits can get transfers to sanctioned areas, there is one more stakeholder in the middle: banks. These banks serve nonprofit clients around the world, many with multimillion dollar portfolios in areas of the world traditionally seen as risky: conflict zones, dictatorships, and areas with scarce infrastructure.

Processing payments to these areas is an extra risk for banks, and often one they are not willing to take. Against the stringent regulatory background of international sanctions law, financial institutions are not incentivized to accept the legal, reputational, and financial risks. Instead, it is easier for them to drop accounts, delay transfers, or deny services altogether. This phenomenon is known as bank de-risking, or overcompliance, and it is perfectly legal. While the U.S. government can forbid transactions with bad actors, they cannot force banks to transact with good ones. The result is that humanitarian organizations struggle to conduct operations in the areas of the world where their resources are needed most.

Impact of Overcompliance on Humanitarian Assistance

Over the course of the past year, I interviewed more than 30 experts to get a better understanding of the risks faced by financial institutions, the policy approaches taken by the U.S. government to address overcompliance, and the impacts on those in need of humanitarian aid. I spoke with sanctions scholars, lawyers advising multibillion dollar banks, U.S. federal officials, and humanitarians speaking from their experiences in Myanmar, Syria, North Korea, Afghanistan, Sudan, and Iran. What resulted was a 50-page policy analysis and recommendations, from which this article is adapted.

Risks Faced by Financial Institutions in Sanctioned Contexts

Understanding sanctions overcompliance must start at the origin of the issue, which lies in the risk analysis of banks. One anonymous humanitarian who experienced significant delays in getting aid to North Korea put it plainly: “There’s no legal reason why banks shouldn’t work with us under the exemptions – it’s fully legal. But rightly so, they don’t want anything to do with business in North Korea; the risks are too great.” Given that banks cannot be legally compelled to process humanitarian transactions, solutions that address overcompliance must prioritize private sector risks and incentives.

Government Fines

The first and most obvious disincentive for banks is the fear of hefty fines leveled at sanctions violators. The most cited case is that of the French bank BNP Paribas, which was fined nearly $9 billion for willfully violating sanctions on Sudan and Iran in 2015. This was just a drop in the bucket of the total fines across the industry. Between 2010 and 2014, the top 16 financial service institutions paid a collective $300 billion in penalties, fines, private settlements, and forensic costs for misdeeds including sanctions busting.

Legal Compliance and Uncertainty

Compliance itself also poses a financial burden. To track and monitor the millions of financial transactions that occur daily, most transnational banks have a computerized risk analysis system that flags potentially risky transfers. Once a transaction is flagged, a compliance officer within the bank manually checks the transaction, attempting to interpret based on the information provided whether it is compliant with sanctions law. Ninety-five percent of American mid- to large-size firms cite sanctions screening as their top compliance challenge, with 36% of their compliance costs going to the salaries of officers who meticulously check transfers by hand.

Put together with the financial market and exchange rate uncertainty that financial institutions already manage daily, introducing ever-changing sanctions increases the incentives for banks to drop accounts in fragile contexts. Banks will assume financial and legal risks when the reward is high enough, but nonprofit accounts in remote locations are rarely the type of billion-dollar return on investment that make uncertain investments worth it.

Reputational Risk

Lastly, large banks face severe reputational risks if they let money get into the wrong hands. The backlash against companies still operating in Russia after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is one such case in point. In one sense this is a positive development—an informed public can make decisions about whether they wish to bank with a company that also counts warlords or despots among its customers. On the other hand, it increases incentives for overcompliance, even in cases of humanitarian need for prisoners of war behind enemy lines.

Reputation is not only important for private customers, but also for public ones. Firms that are too often at odds with OFAC, the FBI, or the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) are less likely to win lucrative government contracts in the future.

Impact of Overcompliance on Humanitarian Actors

Compliance Burden

Financial regulations imposed by both OFAC and private banks impact nonprofit operations at every level from the field to the headquarters. According to one anonymous humanitarian with experience working in Yemen, applications for permits to complete the most basic of tasks were a full-time job on top of humanitarian work. “You’re constantly sending in new applications and asking for approval for extension of your permit,” they said.

Typically, humanitarians must confirm the identity of recipients before they deliver goods and services. However, recipients often do not have the personal identification and documentation required by financial organizations’ compliance departments. According to one interviewee, fragile governments that have data stored digitally may also lose access to that data, making it difficult for recipients of aid to prove their identities. Refugees, internally displaced peoples, and rural populations may not have national ID cards at all, presenting a real issue for banks’ Know-Your-Customer (KYC) requirements.

Costly Workarounds

When bank accounts are not available to purchase goods or process payroll for local workers, humanitarians are pushed to find workarounds that increase security risks or are unnecessarily costly. For example, if humanitarians are not able to provide digital vouchers to local recipients, they may instead carry large sums of cash across borders, a theme reflected in multiple interviews. This is dangerous in sanctioned contexts such as South Sudan or Afghanistan where bribes are exacted at checkpoints—and ironically benefits hostile militaries and terrorist organizations.

Another workaround is engagement with the informal money broker system often used by diaspora groups to send remittances and complete currency exchanges (sometimes called hawala). The Financial Action Task Force, a global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog, released a report on informal channels in 2013 underlining that informal brokers are not inherently criminal and can provide secure, well-documented transfer services. Nonprofits with trusted partnerships with local money brokers have advocated on their behalf, but stigma remains and money brokers are often not able to transfer the volumes of cash needed for an international humanitarian operation.

Delayed, Denied, and Dulled Impact

A drawn out due diligence process by banks or government agencies means that humanitarian efforts may be critically delayed or accounts may be dropped altogether.

Delays in accessing financial resources have an outsized impact in emergency or disaster response situations. The earthquake in Türkiye and Syria in February 2023 is a primary example: lives were saved (or lost) based on the ability of nonprofit organizations to respond within hours. Complicating the issue is the lack of basic infrastructure needed for due diligence, such as corresponding banks that were reduced to rubble. Although OFAC did eventually issue a general license to reiterate the legality of humanitarian transfers to Syria, it came after 72 hours of legal uncertainty.

Even in more protracted contexts, delays caused by financial regulations impact the quality of services. What is relevant and needed at the time of application may no longer be necessary months later, when licenses are approved and funds are released. I spoke with one anonymous humanitarian working in a sanctioned country with widespread childhood malnutrition. They said their organization took 18 months to receive a shipment of soybeans, at which point the local community had given up on the initiative and lost trust with humanitarians in the area who promised results.

Disparate Impacts on Smaller and Muslim NGOs

Regional or local nonprofits have historically played an important role in taking on riskier, more nuanced causes, but they do not have the same resources as multibillion dollar organizations with international clout. A country team for a small nonprofit may have only a handful of lawyers (or one) responsible for compliance with byzantine sanctions regimes.

For smaller nonprofits that do not have existing relationships with large banks, navigating compliance can be daunting. Banks may not publicly share the extent of compliance requirements, so they can reserve the right to delay or cancel payments for undisclosed reasons.

Furthermore, there is evidence that Muslim charities feel the brunt of sanctions overcompliance. Fadi Itani, CEO of the Muslim Charities Forum, pointed to the difficulties that Muslim organizations had sending donations after the 2022 flooding in Pakistan, such as account closure and transfer denial. The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding found that 62% of American Muslims reported challenges with their nonprofit accounts, compared to 17% of general nonprofit account holders.

Policy Responses and Challenges Faced by the U.S. Treasury

Treasury’s Response to Overcompliance

The past few years have seen a significant increase in government willingness to engage on the topic of overcompliance. According to Andrea Hall, Senior Manager of the Together Project and legal advocate for nonprofits,

“In the past two and a half years, we have seen a 180-degree shift in OFAC and even the State Department. We used to explain to the Treasury that if they didn’t help facilitate these funds transfers for humanitarian work, [workarounds were] ironically increasing the risk of terrorist financing. There’s a friendly administration right now that has created an enabling environment.”

Hall attributes the tipping point to the backlash following then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s 2021 decision to designate the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. This tied the hands of humanitarians, as the Houthis controlled access to 80% of Yemen. Within a month, Secretary Blinken revoked the designation, citing the “dire humanitarian situation” in Yemen and “devastating impact on Yemenis’ access to basic commodities.”

The new administration has also taken a lead on overcompliance internationally. In December 2022, the United Nations announced U.N. Resolution 2664, a universal general license for humanitarian work, which was the result of years of advocacy by humanitarian actors and led by the American and Irish delegations. This blanket license, which is intended to dramatically reduce the time required for nonprofits to apply for permits, was soon followed by the U.S. Treasury Department’s announcement of new and amended American general licenses for humanitarian activity.

Although the new and amended licenses are not as comprehensive as some nonprofit advocates had hoped, “the fact that the U.S. was able to lead a U.N. Security Council process to create this humanitarian exemption signals a massive change in position for the U.S. government, which sets the tone for these things,” said Jacob Kurtzer, a humanitarian researcher and aid expert. “The problem is,” he added, “that achieving the end goal of domestic implementation is going to take a very long time.”

Immediate Next Steps

Given the complexity and scope of the issue, sanctions overcompliance can seem like an intractable problem. Each stakeholder is balancing high-stakes priorities: billions of dollars in assets, national security, political power, and life-saving humanitarian response. However, there are two immediate actions the U.S. government could take in the short-term to address overcompliance.

The first step should be a USAID-funded grant to train bank compliance officers on nonprofit financing and share best practices with U.S. grant partners. Why USAID? Because they stand to lose the most through overcompliance: they spent $32 billion dollars on non-reimbursable grants to its partners throughout the world last year, many of which are small nonprofits in conflict zones. USAID relies on these nonprofit contractors to enact their programmatic goals, but a 2019 report found that 43% of the agency’s awards achieved just half of their intended results.

USAID is aware of this issue – and was a contributing supporter of the Center for Strategic International Studies’ 2022 multistakeholder dialogue on overcompliance. Still, they could take a more active role in public-private partnerships needed to address the issue.

A second short-term solution with immediate impact is an automatically triggered 24-hour general license in response to acute natural disasters. The benefits of this solution are that it is difficult to exploit (the window is limited and disasters are unpredictable) and it would prevent the deadly consequences of delays in the hours following a tragedy. In a world facing greater threat of climate disasters, it is also proactive instead of reactive.

Specifications such as the length of the window, definition of “acute,” and which disasters qualify are worth careful consideration. Still, a few hours’ assurance would have made all the difference to the survivors of Syria’s earthquake and the banks processing the donations needed to dig their relatives out of the rubble.

These two steps are the first in a longer-term strategy needed to streamline bank compliance, support humanitarian assistance abroad, and modernize financial sanctions as we move into a new era of foreign policy.

Photo credit: Neryl Lewis via Wikipedia Commons