Stretching from the Atlantic coast in the west to the Red Sea in the east, the region of north-central Africa known as the Sahel has rarely figured as a focus of international geopolitics. Yet this semi-arid band of territory, spanning some 14 countries and home to numerous ethnic and religious groups, is emerging as a new arena in the sprawling global battle between governments and jihadist groups. Effective government has long been absent from much of the dry Sahelian steppes and grasslands, along with the vast reaches of the Sahara Desert to the north. This has left large tracts of land in which a plethora of militant and criminal groups, some with ties to al-Qaeda and Islamic State, have come to operate with relative ease. Even as the military situation in Syria and the political crisis in Palestine attracts much of the international community’s attention and resources, the burgeoning governance vacuum on the southern approaches to the Mediterranean should be a source of increasing concern for policy-makers in Europe and North Africa.

This zone of instability is not the result of a unified jihadist programme in the mode of Islamic State, but rather comprises a patchwork of local conflicts fuelled by local grievances which extremists have attempted to leverage for their own interests. In Mali, long-simmering resentment amongst northern Touareg communities at perceived neglect by the central government boiled over into a rebellion in 2012. While the major rebel groups are now engaged in an ongoing, if stuttering, peace process with the authorities in Bamako, armed violence continues to plague northern and central areas where the government’s authority remains weak. Extremist jihadist groups, with whom the northern rebels were initially affiliated in an alliance of convenience, continue to exploit this instability, targeting both the Malian government and the United Nations peacekeeping force stationed there.

In a sign of increasing coordination between various Islamist factions, four prominent armed groups announced in mid-2017 their merger as Nusrat al-Islam, proclaiming their allegiance to al-Qaeda. The alliance between Ansar Dine, which participated in the Malian rebellion, al-Mourabitoun, led by seasoned Algerian militant Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the Sahara wing of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the ethnic-Fulani Macina Liberation Front, presents a major challenge to the under-resourced security forces of the region. As well as targeting state security forces and UN personnel, these groups have carried out attacks against civilian targets in the Malian capital of Bamako, in Burkina Faso, and even as far south as Côte d’Ivoire. During these attacks they have sought out and killed both local and foreign civilians. Another concerning development is the nascent local Islamic State franchise—Islamic State in the Greater Sahara—which, while relatively small, is suspected to be behind several attacks in Niger and Burkina Faso. These vast, sparsely-populated areas in which borders are largely theoretical, has provided fertile ground for the activities of these militants. Many al-Qaeda-linked groups in northern Mali, and throughout the Sahel, have embedded themselves in Sahelian communities, fusing their extremist ideology with the more parochial concerns of the locals whose support they seek; the alliance between AQIM and Touareg rebels is one such union. This strategy makes these groups no less dangerous than Islamic State, whose unflinching and at times apocalyptic commitment to creating a global caliphate is not always popular with the communities in which it is based. The more measured public posture of these extremist groups has given them greater cachet with local populations than the austere Islamic State ideologues have garnered.

The danger to Sahelian states from these groups derives not only from their propensity to target civilians and state institutions alike, but also from their evinced strategy of feeding on political instability to expand their zones of operation and integrate their activities with other extremist groups. While these links are often informal, and rely significantly on the itinerancy of individual militants between different factions, the shifting array of Saharan-Sahelian extremist groups represent a serious threat to regional security. The Nigerian Islamist group Boko Haram now comprises two major factions, one of which, previously having enjoyed operational links with al-Qaeda, is now recognized as the regional Islamic State affiliate. These groups stalk remote areas of the Lake Chad basin, launching guerrilla-style attacks on civilians and the governments of Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. Sahelian governments worry that Boko Haram factions may seek deeper organizational ties with other extremist Islamist groups in the Sahel.

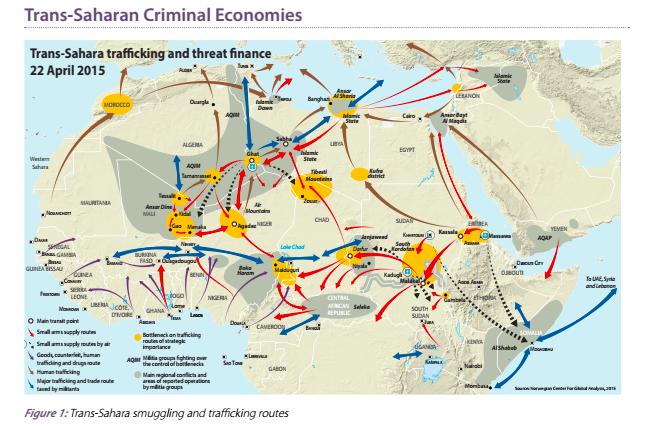

At a broader level, governments in North Africa and Europe are acutely aware of the danger posed by shifts in the regional jihadist landscape in the southern Mediterranean basin. As the conflict with Islamic State in Syria and Iraq winds down, there is a risk that the rugged spaces of the Sahel and the Sahara may provide refuge in which harried fighters can rebuild their militant networks. Extremist groups including al-Qaeda and Islamic State have exploited chaos in Libya to entrench themselves throughout the country (despite the latter losing much territory in the last year), and develop operational capacity in parts of neighbouring Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt. In light of the well-known porousness between the southern borders of these countries and the states of the Sahel, there exists a real risk of extremist groups across the region forging or strengthening their connections. The Sahel is already home to an entire illicit economy based on trans-Saharan trafficking—of drugs, arms, and people—and routes used for these purposes can also facilitate the movement of extremists. In addition, this transnational trade serves as an important source of funding for militants. And, just as the largely unmonitored reaches of the Sahara allow for greater interaction between militants, regional governments also fear the possibility of extremist groups competing amongst themselves for followers and publicity by committing spectacular attacks on prominent targets in the Sahel.

Governments have not ignored the existence of this threat. Several distinct forces are involved with military responses to Sahelian insurgencies. The G-5 Sahel group—comprising Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania—is the sort of regional-level response that is necessary to address trans-border criminal and militant networks. However, it is hampered by a funding deficit which, in light of the poverty endemic in its member states, will need external backing to rectify. It also lacks the enthusiastic support of Algeria, a regional power in whose territory many of the jihadist groups originated, and whose intelligence agencies possess valuable information that could aid the fight against these groups. It is believed, however, that Algeria views the G-5 as an instrument of France, its former colonial occupier whose intentions in Francophone Africa the Algerians do not entirely trust. Indeed, France has been a prominent military player in the region, committing 4,000 troops in support of the G-5 as part of a counter-terrorism mission called Operation Barkhane. Other international players include the United Nations force in Mali, MINUSMA, and United States Special Operations troops, who provide both training and armed support to local militaries.

Yet, while terrorist groups need to be dealt with militarily, the wider instability on which they feed is largely the result of local grievances in Sahelian states that many observers believe must be addressed at a political level. Extremist groups have taken root in some of the most impoverished regions of the already-poor states of the Sahel. These areas suffer from lower levels of healthcare, education provision, and job opportunities than other parts of these countries, while the agricultural livelihoods through which many residents make a living are increasingly threatened by desertification and other impacts of climate change. The United Nations has noted the necessity of addressing the root causes of the “interconnected challenges” of “[v]iolent terrorism, armed conflict, extreme poverty and underdevelopment, climate change, displacement and the smuggling of people, drugs and arms” that fuel the crisis. The UN is nonetheless “acutely aware of the need to go beyond security measures” in addressing instability in the Sahel. It is promoting a multi-agency drive to advance economic development, improve job and food security, and strengthen governance structures and the provision of vital services to marginalized communities.

At the same time, the UN has stressed the need for the process to be “led by national Governments.” Indeed the reform of governance structures in many Sahelian states will be crucial to ameliorating the deep wells of local resentment which extremist groups have exploited. The participation of marginalized areas in national political processes, the increased provision of essential services to these areas, the equitable division of natural resources and distribution of profits arising from these, and legal provision for increased local governance must all be considered. Doctrinaire extremists may need to be met with military force, but governments can diminish these militants’ leverage over more locally-focused and less extreme groups by addressing the political and economic challenges of disenfranchised communities. Only by dealing with the structural problems that have generated political instability and fuelled public grievances in the rural Sahel can these states hope to effectively counter the influence of extremist groups. Wealthier countries in the West—whose own interests are also undercut by an unstable Sahel—must commit to aiding Sahelian states in this important work.