Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón received the Oscar for best director for his beautiful masterpiece Roma at the 91st Academy Awards. As he was handed the statue from another Mexican director, Guillermo del Toro, he said: “I want to thank the academy to recognize a film that is centered around an indigenous woman, one of the 70 million domestic workers in the world without work rights, a character that has been relegated from the cinema.”

Indeed, one of the achievements of Roma was that it made visible several problematics. Among them, it raised the delicate question “is Mexico racist?”

The answer came fast. Yalitza Aparicio, who plays the role of Cleo in Roma, was attacked on social media by (some) Mexican public and colleagues as she posed for fashion international magazines and being nominated for “Best Performance Actress”. The Mexican saying “even if the monkey dresses in silk, monkey stays” was amongst the common attacks.

These attacks are symptoms of the deeply anchored racism and colorism in Mexico. It is so implicit and entrenched in Mexican idiosyncrasy that when it comes to light, it is inevitably uncomfortable. According to the 2017 National Survey of Discrimination, 64.6% of the population self-identifies as brown. Yet, it is rare to see this skin tone in news programs, soap operas, and movies. At least not the main character. An indigenous tv anchor? No way. The perfect example of how itchy is, for some groups, see indigenous people in media was the most recent edition of Hola Magazine, a socialite publication, that whitened and thinned Yalitza for its cover page. Fortunately, it was severely criticized.

It is important to recognize Cuarón’s efforts to portray the experience of a Mexican domestic worker to “make visible a problem that is rooted in our closest circles.” But we have to take a step back in attributing Cuarón and Roma role of the social justice redeemers. There are several voices that think that the film will change the beauty narratives and that it will revalue the indigenous minority in Mexico. Even National Public Radio falls into this falls into this dialectical turmoil of Mexican recent history by paraphrasing “Aparicio’s appearance in the movie, with brown skin like its own, seemed to be proposing a new standard of beauty.”

How could her appearance be a new standard of beauty? The role of the fantastic Yalitza must be observed with caution. Roma masterfully shows the harsh reality of two women and their dialogue with absent men and how the reality of each is shaped by their different identities. I found heartbreaking Roma’s last sequences, where Cleo goes from losing her newborn son in the hands of careless physicians, to having to save her patron’s children in the sea without knowing how to swim. As a mere depiction of that reality, Roma is not trying to propose indigenous groups as new beauty standards and made no effort to change the prevailing discriminatory schemes and narratives for indigenous groups. If having an indigenous woman as a domestic worker, socially obligated to serve their patron’s despite their well-being, is a new “standard of beauty”, we are then into the conservatism business.

Furthermore, the instrumentalization of Rome as a flag of the fight against discrimination is very dangerous. Roma is a piece of art, but that is it. In the eagerness of the big producers to obtain an Oscar, media campaigns love inclusion and diversity. The danger of these campaigns is the simulation of reparations—or as a classmate said, the “hypocrisy of democracy.” That is, that their superficiality may be confused with real reparations, that eventually, cover the need for concrete policies to battle systemic discrimination.

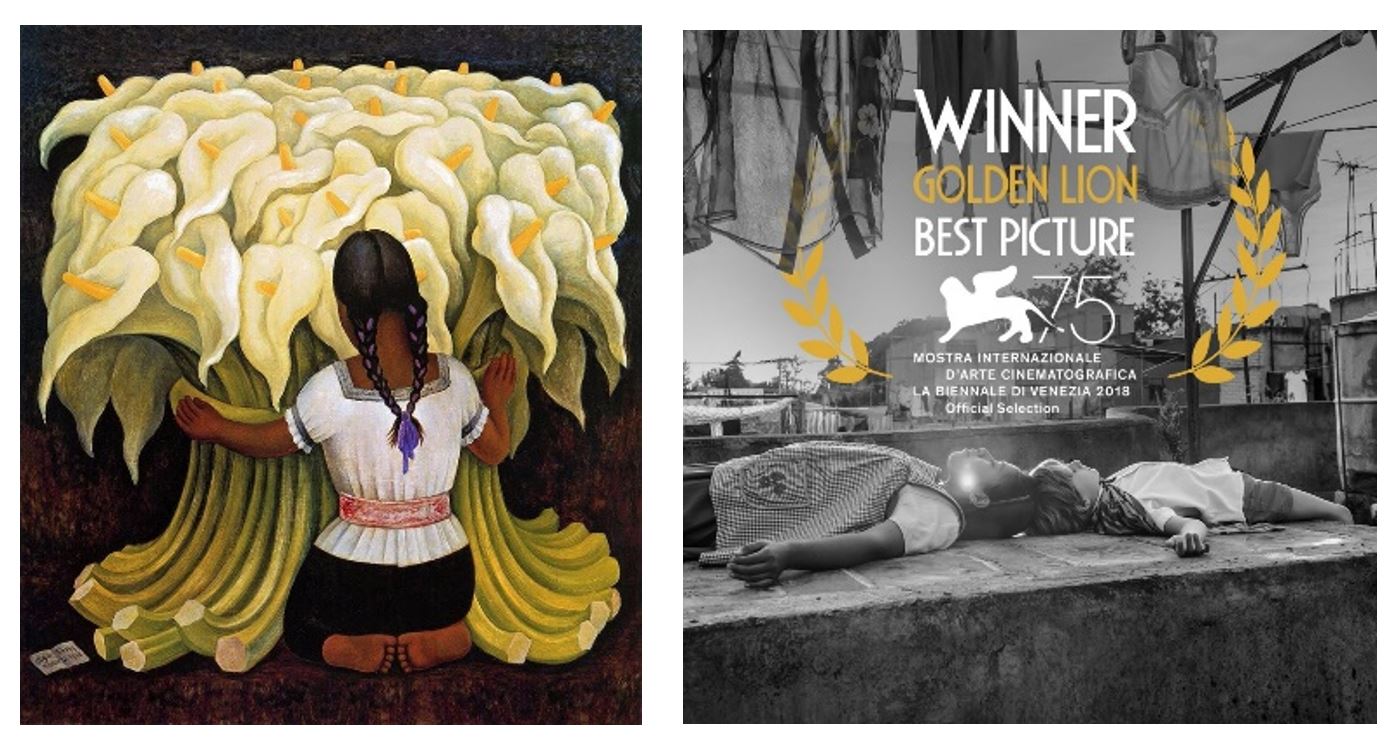

This revalorization effort—or being aggressive, I call it simulation—has found its core within Mexican art. I would that art that emerged in Mexico after the Revolution, a civil conflict at the beginning of the XX century, and whose objective was to reevaluate Mexicanity from its indigenous roots, has done more damage imagery than good, to these groups. Historically, the artistical platform of Mexico’s most prominent artists, such as Diego Rivera, Alfaro Siqueiros, and even Frida Khalo, thinkers like José Vasconcelos and Mexico’s only literature Nobel laureate, Octavio Paz, were based on portraying the indigenous beauty. While these geniuses were not guilty of their privileged unconscious bias, they have prolonged a discourse that indigenous groups’ beauty is attached to their humble, autochthonous, barefoot countryside-nature. Unconsciously or not, Cuarón’s art flows naturally into this narrative accentuating nothing but the stereotype and position for the indigenous women in Mexican society: silent at the bottom.

The painting “Desnudo con alcatraces” (Diego Rivera, 1944) and the poster for the movie “Roma” (Alfonso Cuarón, 2018) both show an indigenous woman in their “typical” clothes.

What can we do about it? The answers are intuitive, and despite that, they seem too complex to be implemented in countries like Mexico (and Latin America).

First, we should be aware of our history and constantly read between the lines on the inherent power relations of the creators and the spectators. While we might not able to demand social justice from every film, we must not wrongly attribute one a social justice flag. Furthermore, we should avoid the continuing idiosyncratic normalization of some groups’ superiority over others, and, especially, we cannot tolerate the usage of certain phenotypes to both simulate reparations and decorate settings.

Second, we must keep looking for different kinds of stories told from non-privileged perspectives. While we have acclaimed the art of ones elevating it to masterpieces, we have reduced the art and stories of indigenous to an inferior position. In this turmoil, what is already beautiful is again and again “rediscovered” as a new parameter of beauty. As Galeano’s “Los Nadies” poem powerfully expresses, we have reduced the art of indigenous groups to the runner-up position of “artesanías” and “folklore”. Second class art for second class citizens.

Finally, affirmative representation in movies. Directing a movie with an indigenous superhero? Why not? Despite being chosen the best director, Cuarón’s Roma falls behind same year’s nominees like Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman and Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, in terms of the social justice debate. The former portrays an African American police that infiltrates Ku Klux Klan, while the latter an African king and superhero. Hopefully, Mexican artists will go further with a braver dialogue to question our actual schemes and try to actively change them from their privileged perspective.

Sadly, this might be far. At the beginning of February, at the Mexico Conference 2.0 held at Harvard Kennedy School, I asked about Roma and about affirmative representation in Mexican movies to Diego Luna, one of the most recognized Mexican actors and friend of Cuarón. He responded that (with respect of having an indigenous woman as a president in a film) “it might not be possible, not now, as movies are a depiction of reality… if it happens, it would be a fictional movie”. And somehow, I just knew that the great Mexican artists are not ready to be that brave.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Latin America Policy Journal.

Photo Source: Carlos Somonte