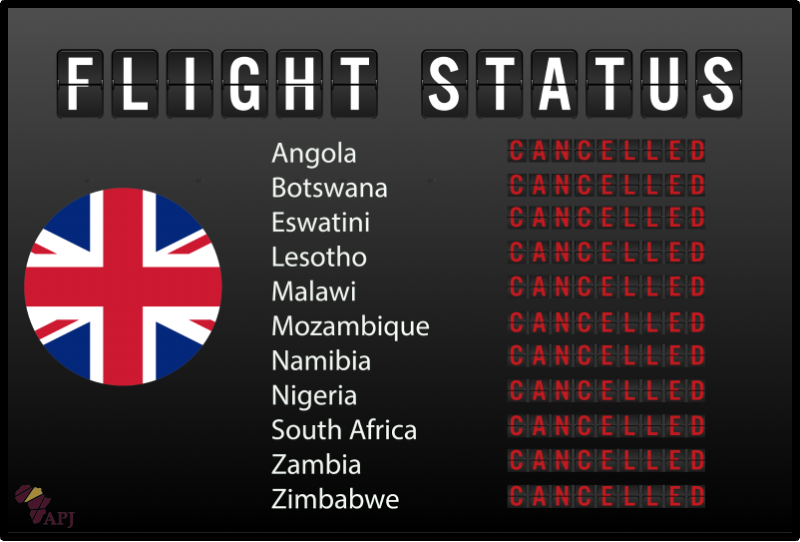

The UK Government recently abandoned its controversial red list, which had only allowed UK citizens or residents traveling into the UK from Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, but not residents of those countries. The UK Government has now deemed the policy “no longer effective or proportionate” as the Omicron variant of COVID-19 has continued to spread not only in the UK, but in countries around the world.

I dare say that those measures were never effective or proportionate in the first place. When travel restrictions on the 11 African nations were announced by the European Union, UK, USA, and Canada following the reported discovery of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant by South Africa, experts condemned the move strongly. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, termed it “travel apartheid.” The emergence of variants is an expected survival strategy for viruses as they seek new ways to continuously infect people and bypass immune responses. Therefore, the science shows that mutations and variants were the expected order of things, and “entirely predictable” according to the World Health Organization’s Assistant Director-General and Chief of its Pandemic Intelligence Unit Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu.

Lessons from the ongoing pandemic have shown that travel restrictions are most effective when they are implemented rapidly, before they have had a chance to spread beyond borders. Not when the variant had already been detected on virtually every continent and in over 20 countries, including the Netherlands, the UK, Australia, and Japan. Some nations such as Netherlands, had already been infected with the variant before South Africa reported it to the World Health Organization. The Omicron-related border closures were unfortunately considerably late.

The ensuing travel restrictions were therefore not only too late, but no more than a political move to give the public a ‘false sense of security’, and feed a perception that government was taking concrete action against Omicron.

Beyond restrictions on movement for passengers from banned countries, there are far-reaching implications of these travel restrictions.

For one, such political grandstanding is counter-productive and challenges already-existing and effective preventive measures such as wearing of face masks, hand hygiene, physical distancing, and people-centered messaging to encourage vaccines uptake. By propagating communications about travel bans in situations where they are known to be ineffective, governments unwittingly send a false message to the public that this is all that is required to keep them safe, thus undermining the true ways to control the COVID-19 spread.

Another disadvantage of these knee-jerk travel bans is that they delay urgent research on variants, by delaying the arrival of imported lab supplies, and creating difficulties in the sharing of samples across countries that would help scientists understand the virus better.

Additionally, these restrictions stigmatize countries, and actively deter countries from sharing valuable scientific discoveries with the world.

Travel bans are a distraction, and for as long as governments continue to be fixated on them, we lose sight of what is truly important if we are to win this battle against COVID-19.

The pandemic has illustrated many inequities, and travel restrictions are yet another example. According to global COVID-19 vaccination data, while 58% of the population in Europe and US have been fully vaccinated, only 7.3% of Africans are immunized. Inequitable vaccine distribution from the beginning has been a major contributor to this. Vaccinations in high-income countries, where governments could afford to secure several millions of vaccine doses, began in December 2020. Vaccinations in Africa, however commenced months later, and the continent has struggled with getting sufficient numbers of doses for their populations. Meanwhile, as of early November, a mere 12% of the 1.9 billion doses promised to low and middle income countries had been delivered.

Beyond available vaccine quantities, distribution challenges have heightened vaccine hesitancy. African countries have struggled due to vaccines supplied with a few months and sometimes weeks to expiry. Dr Ayoade Alakija, who co-chairs the Africa Union Vaccine Delivery Alliance, has compared the vaccine donations from G7 countries to a “Trojan horse”, with concerns that their limited shelf life could be detrimental to pandemic-containment efforts. According to Kenyan political analyst Nanjala Nyabola, “We are setting up African countries to fail with leftover vaccines”.

In the spirit of global cooperation, G7 countries should support African countries in developing local capacity for vaccines manufacturing, with intellectual property waivers and knowledge-transfers that would enable this. Conversely, countries on the continent must also show themselves keen on building local capacity for research, innovation, and technological advancement.

The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated airline emergency guidelines which stipulate that one puts on their own oxygen mask before helping others. Whereas G7 countries have done exactly this, those guidelines do not describe differences between oxygen masks. African countries have therefore found themselves with the shorter end of the stick. As Cheikh Oumar Syedi, Director, Africa, of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation recently pointed out, Africans are – “last in line for vaccines, but first in line for travel bans”.

Clearly, SARS-CoV-2 is our common enemy. Only by working together to strengthen each other will we win this fight against COVID-19 and its lengthy retinue of present and future variants.