With an economy long buoyed by oil, Saudi Arabia is beginning to feel the pinch for the first time in decades. The Saudi economy grew at a meager rate of 1.4% in 2016, as the war effort in Yemen and low global oil prices began to take their toll. This forced the government to raise $9 billion through issuing Islamic sovereign bonds (sukuk). Pouring salt on these wounds, the kingdom’s cash woes have weakened Saudi Arabia’s check-book diplomacy – traditionally one of the Gulf state’s fortes.

The launch of the kingdom’s “Vision 2030” last April was an effort by the Saudi government to address these financial and strategic challenges over the next 15 years. At the heart of Vision 2030 is a commitment to diversify the Saudi economy by reducing its reliance on oil, and increasing the share of renewable energy sources to 9.5 gigawatts (GW) by 2023. It is believed that if domestic oil demand is allowed to grow unabated at the current rate of over 9.5% per year, the kingdom would have to cut its oil exports to below 7 million barrels a day, from the current level of 10m barrels a day.

The Saudi strategy is, therefore, aimed at reducing the domestic consumption of crude oil by introducing renewables. International competition is also behind the shift to green energy, especially due to U.S. shale oil production. The falling operating costs of firms involved in shale oil exploration and drilling, together with the flurry of investments in this sector, have made shale oil prices increasingly competitive.

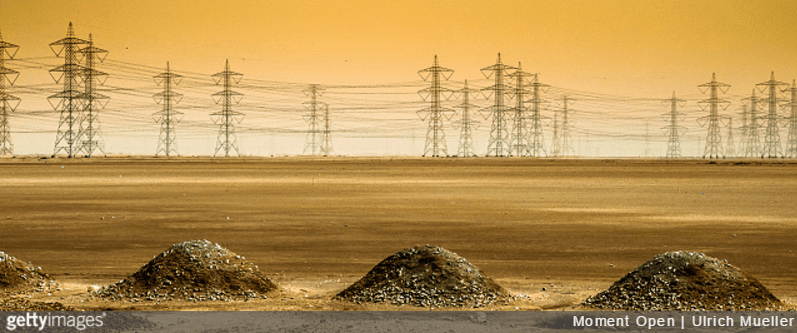

The recent Saudi strategy to neutralize shale oil’s competitive advantage by flooding the market with cheap oil has not, however, brought Saudi Arabia the hoped-for reprieve. The kingdom’s policymakers are worried that they are fast losing the dominant position they once enjoyed in oil markets. This realization has led to broad institutional shake-ups under King Salman – such as the integration of energy, industry and mineral resources under the umbrella of a single ministry headed by Khalid Al-Falih, the former CEO and current chairman of Saudi Aramco. The Ministry of Water and Electricity was abolished, and Al-Falih was also given control of the Saudi Electric Company (SEC), which enjoys a monopoly in power transmission and distribution across the kingdom.

Central power

At the helm of Saudi Aramco and SEC, the all-powerful Al-Falih is now the key decisionmaker for the recently unveiled King Salman Renewable Energy Initiative. Soon after assuming office, Al-Falih created a Renewable Energy Project Development Office (REPDO) with representation from all the major stakeholders in the energy sector. In its first phase, REPDO intends to install 700 megawatts (MW) of solar and wind power, with a medium-term target to have 3.45 GW (or 4% of total energy consumption) installed by 2020.

The office has been open to public-private partnerships, in which the government provides land and grid connectivity, while investors construct solar and wind farms on a “BOO” (Build, Own, Operate) basis. BOO contracts were used to award bids for the 300-MW “Sakaka” solar power project in northern Saudi Arabia, and the 400-MW “Midyan” wind farm project in the country’s northwest. The consolidation of conventional and renewable energy under one portfolio heralds a centralized approach in which fossil fuel and renewable generation will operate side-by-side in the kingdom.

While new solar and wind farms will boost Saudi foreign exchange earnings from oil, an increase in employment opportunities is likely to be an additional benefit. The unemployment rate, which currently stands at 40% among Saudi youth, is a major concern for the government. With about 130,000 more Saudi students graduating with a university degree every year, the severity of the problem could well increase in coming years. The kingdom’s oil and gas sector, by far the largest sector of the economy, is already highly mechanized, with limited capacity to absorb unemployed youth. The government therefore desperately needs to create new avenues for employment, and to keep a check on the level of discontent caused by subsidy cuts and the slashing of public-sector bonuses.

In the U.S., the solar and wind energy sectors have started to create jobs 12 times faster than the rest of economy, thanks to economies of scale and substantial reductions in manufacturing and installation costs. This success story can be replicated in Saudi Arabia, which enjoys yearlong sunshine and a strong potential for wind power, especially in its coastal cities.

What can be done?

For Saudi Arabia to make domestic renewables competitive, the country needs to introduce a more market-based pricing mechanism for oil, especially for the residential sector, which is responsible for almost 50% of domestic electricity use. The Saudi government has already made the hard decision to increase electricity tariffs. If this is followed by judicious patronage of renewable energy, such price hikes could be brought down on a sustainable basis.

As an immediate measure, the government can supplement its efforts by supporting private start-ups and promoting foreign direct investment in renewables. Given its huge potential to develop renewable energy sources – especially solar – Saudi Arabia could export electricity to neighboring Yemen, Egypt, and Jordan. From a geopolitical vantage point, this would bolster Saudi’s strategic advantage over other regional competitors.

Saudi ambitions in the renewables sector must be backed by strong legislative, regulatory, and investment frameworks. This is even more important since the kingdom has set the target of attracting $30-50 billion in investments in renewables by 2023. At present, there is no formal policy document, except the broad goals enshrined in Vision 2030. This creates uncertainty and does not inspire confidence in potential investors. Accordingly, the government must sit with private-sector investors, technology firms, financial institutions, and academia to formulate a detailed policy document.

Another impediment to developing renewables is the lack of human resources available domestically. The general preference of Saudi nationals for administrative jobs over technical ones has hindered the development of a local pool of talent. Most technical jobs are still filled by foreign expatriates, contributing to capital flight through remittances to their home countries. This technical gap can be addressed by strengthening elementary education and vocational training programs.

In the renewables sector, an effective strategy would be to incentivize solar panel and wind turbine manufacturing firms to establish plants in the kingdom. This would offer local workers exposure to state-of-the-art technologies. At the same time, the government should consider providing subsidies on renewable energy equipment. The Korean and Chinese models of technology development, which are based on reverse engineering, offer examples to follow that could help lay the foundation for producing technology domestically in the long run.

A Saudi evolution to a green energy future is possible and within grasp. But it will require persistence, strategy and hard work, from both the government and citizens.