BY KATIE MONROE

Desiree,[1] 40-year-old mother of two children, wanted to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. As she had health insurance through Medicaid, it did not cover abortion, and the full cost of the procedure was more than she could afford.

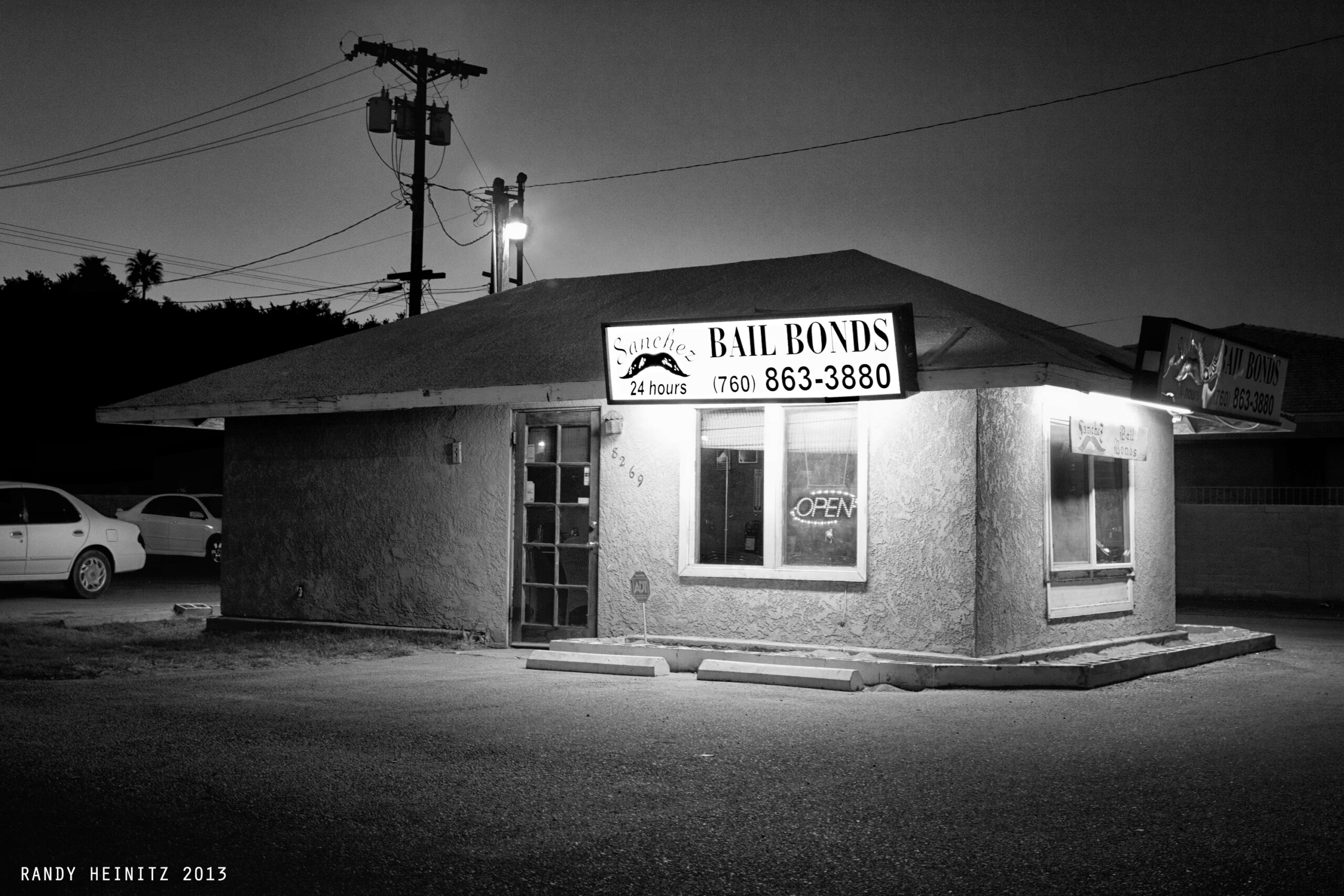

Kim, a pregnant mother of two, was arrested and needed $2,500 to post bail, which is prohibitively expensive. A similar defendant with more cash on hand would be able to walk free, whereas Kim faces pre-trial detention.

What do these stories have in common? In both cases, unjust policies in the American health care and criminal justice systems restricted these women’s access to basic rights—bodily autonomy and physical freedom—simply because they lacked financial resources.

Fortunately, they had another thing in common: both Desiree and Kim were ultimately able to access the funds they needed. Desiree received $105 from Women’s Medical Fund (WMF), a nonprofit abortion fund based in Philadelphia.[2] The funds allowed Desiree to receive an abortion. Another local organization, the Philadelphia Bail Fund, posted the $2,500 Kim needed for bail. After several months of fighting her case from home, Kim’s charges were dropped.[3]

The two organizations that stepped in to help Desiree and Kim also have much in common. While they work in different spheres, abortion funds and bail funds are distinctly parallel types of organizations in the United States. Both fundraise to meet the immediate financial needs of clients like Desiree and Kim. And both advocate for changing the policies that make their form of private aid necessary in the first place.

The parallels between abortion funds and bail funds reveal (at least) two major lessons. First, policy makers should look to these organizations for leadership and direction: to abortion funds for reproductive healthcare policy insights and to bail funds for valuable insights about bail reform. Second, abortion funds and bail funds have much to learn from each other, since they—and the people they serve—face corresponding and intertwining challenges.

Advocacy Built on Proximity to the Problem

As Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) puts it, “the people closest to the pain should be closest to the power.”[4] Abortion funds and bail funds interact every day with people who are acutely harmed by policies that disproportionately affect individuals with fewer financial resources. These organizations offer frameworks to both address the concerns of their clients and use those concerns to inform policy advocacy.

Abortion funds have a central policy goal: the repeal of federal and state bans on public funding for insurance coverage of abortion.[5] Just three years after Roe v. Wade established the right to terminate a pregnancy, the 1976 Hyde Amendment blocked federal funding for abortion care, effectively denying this right to millions of low-income people on Medicaid, except in cases of rape, incest, or when the life of the mother is threatened.[6] Similar or even more-restrictive policies apply to state Medicaid funding in 35 states.[7] While grassroots abortion funds across the country try to fill the need by granting money directly to people who cannot afford abortions, reversing these restrictive policies remains crucial to making the rights promised by Roe real for everyone.

Abortion funds bring unique insights to policy debates about abortion access. In January 2019, the nonprofit WLP in Philadelphia filed a lawsuit challenging Pennsylvania’s state Medicaid abortion-coverage ban on the grounds that it violates Pennsylvania’s Equal Rights Amendment.[8] Women’s Medical Fund filed an amicus brief to support WLP’s suit, offering stories from the callers they speak with every day to illustrate the human impact of restrictions on abortion funding.[9] The brief shared heartbreaking stories of people “forced to choose between meeting basic needs—like paying for groceries, rent, and utility bills—and using that money for the procedure,” with some callers still unable to scrape together sufficient funds to terminate their pregnancies even with support from WMF.[10] The experiences of WMF’s clients should serve as a stark reality check for policy makers personally insulated from these types of decisions.

In parallel fashion, bail funds seek to eliminate cash bail as part of the pre-trial criminal legal process while posting bail for defendants who need it in the meantime. The National Bail Fund Network calls bail funds “the tip of the spear for local and state policy reform within multi-pronged bail-reform campaigns.”[11]

Pre-trial detention destabilizes the lives and families of defendants, costing people their wages and jobs and custody of their children.[12] Additionally, pre-trial detention makes it logistically and psychologically more difficult for defendants to navigate the criminal justice system. Empirical analysis suggests that defendants detained pre-trial disproportionately accept plea deals, even when they did not commit the crime.[13] These findings, combined with bail-fund advocacy, have compelled many cities and states to launch bail-reform efforts.[14]

Like abortion funds, bail funds offer crucial insights about needed reforms. Many bail funds, including the Philadelphia Bail Fund, have organized “bail watch” efforts, where members of the public regularly observe bail hearings firsthand in order to understand the current process and advocate for improvements.”[15] In their 2018 Philadelphia Bail Watch Report, the Philadelphia Bail Fund noted several specific practices that they learned disadvantage defendants, including using video conferencing during preliminary arraignments.[16] This is the kind of specific, actionable insight that policy makers who want to improve the pre-trial process need to pay attention to.

Solidarity and Learning between Bail and Abortion Funds

Because bail and abortion funds have parallel organizational models and serve overlapping populations, they also face parallel challenges in operations, communications, and advocacy. These organizations can learn from each other’s triumphs and challenges to benefit both abortion-fund clients and the defendants who access bail-fund resources.

The scale of the problems abortion funds and bail funds seek to address outpaces the organizations’ financial resources. In 2017, abortion funds throughout the country supported 28,837 people, who were only 19 percent of the people seeking help from abortion funds that year.[17] While bail funds have the benefit of a “revolving” model, where funds can be reused to post bail for multiple defendants, they likewise struggle to maximize harm reduction in the face of overwhelming need.

The Chicago Community Bond Fund (CCBF) has developed an innovative way to make tough decisions amid resource constraints. When determining who should receive bond support, CCBF delegates decisions to a review committee composed of community members involved in racial justice efforts in Chicago.[18] In doing so, CCBF entrusts those disproportionately affected by mass incarceration to determine the most equitable means of deploying their limited funds, potentially serving as a model to other bail and abortion funds.

Also, both abortion and bail funds strive to communicate their work in a nuanced and ethical manner. Given the stigma associated with abortion and incarceration, both types of organizations must be thoughtful about how and when they share clients’ stories with donors, the media, and policy makers. The National Network of Abortion Funds (NNAF), an organization supporting the work of abortion funds throughout the country, has an exemplary leadership and communications program called “We Testify,” which seeks to “build the power and leadership of abortion storytellers.”[19] NNAF supports a diverse cohort of people who have had experiences with abortion so that they can tell their own stories on their own terms, a communications model useful to both bail and abortion funds.

One story from a “We Testify” storyteller shows how the work of these types of funds overlap and highlights the need for shared learning. In an article for Bitch Media, Kay Winston described her experience being pregnant and incarcerated in Ohio. She wrote, “When I was incarcerated, I was denied an abortion when I asked for one, even though it’s nearly impossible for those who are in prison to access basic prenatal care. . . . It was the most terrifying time in my life.”[20] Winston’s story illustrates the fact that reproductive and criminal justice do more than run parallel; they intersect directly in the lives of many people.

Some abortion funds and bail funds have already recognized their overlapping work and taken joint action. For example, Yamani Hernandez, executive director of the National Network of Abortion Funds, shared in an email that “at the [2018 NNAF] summit, we presented the Chicago Bond Fund with a cash award to support their efforts, and I spoke at the National Bond Fund Network conference.”[21] In 2018, the Texas Equal Access Fund, an abortion fund in northern Texas, called on their supporters to donate to the “Black Mamas Bail Out” national bail-funding campaign.[22] These collaborative efforts have the potential to grow. Hernandez noted that, “We look forward to deepening our work together, especially as abortion is increasingly criminalized and may require bond funds, and vice versa.”[23]

The Future of the Funds

Speaking about the parallels between bail and abortion funds, Women’s Medical Fund Executive Director Elicia Gonzales said, “The nature of this work is a demonstration of how policies, by design, are attacks on poor people.”[24]

Abortion funds and bail funds illuminate the impact of these policies, compassionately reduce the harm inflicted by these policies in the short term, and advocate for systemic change in the longer term. As they strive to realize their respective missions, these organizations should continue to look to each other for ideas and mutual support. Policy makers who hope to ameliorate the injustices of our country’s reproductive health care and criminal justice policies would also do well to look to abortion funds and bail funds for direction.

Katie Monroe is a master in public policy student at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and serves as the co-chair of the Gender Policy Union, a student organization. She is interested in the equity and accessibility implications of emerging transportation technology in cities and has worked on bike-share, e-scooter, and autonomous-vehicle issues in Philadelphia and Boston.

Edited by: Samantha Batel

Photo by: Randy Heinitz, Flickr

[1] Names have been changed to protect individuals’ privacy. Inspiration for the title of this article from Women’s Medical Fund, Wisconsin. Twitter Post. 21 July 2018, 10:21 PM. https://twitter.com/WMFwisconsin/status/1020871423747940352.

[2] “Who Do We Help?” Women’s Medical Fund, n.d., accessed 17 January 2019, http://www.womensmedicalfund.org/who-do-we-help.

[3] “Results,” Philadelphia Bail Fund, n.d., accessed 17 January 2019, https://www.phillybailfund.org/results/.

[4] E.J. Dionne Jr., “Boston couldn’t wait for change,” The Washington Post, 5 September 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/boston-couldnt-wait-for-change/2018/09/05/ceebcb38-b13c-11e8-9a6a-565d92a3585d_story.html.

[5] “Our Political and Cultural Agenda,” National Network of Abortion Funds, n.d., accessed 18 January 2019, https://abortionfunds.org/political-cultural-agenda/.

[6] Heather D. Boonstra, “Abortion in the Lives of Women Struggling Financially: Why Insurance Coverage Matters,” Guttmacher Polic Review 19 (2016), https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2016/07/abortion-lives-women-struggling-financially-why-insurance-coverage-matters.

[7] “State Funding of Abortion Under Medicaid,” Guttmacher Institute, last updated 1 March 2019, accessed 11 February 2019, https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/state-funding-abortion-under-medicaid.

[8] Tara Murtha, “Pennsylvania Abortion Providers File State Lawsuit Challenging Medicaid Abortion Coverage Ban,” Women’s Law Project (blog), 16 January 2019, https://www.womenslawproject.org/2019/01/16/pennsylvania-abortion-providers-file-state-lawsuit-challenging-medicaid-abortion-coverage-ban/.

[9] Murtha, “Pennsylvania Abortion Providers File State Lawsuit Challenging Medicaid Abortion Coverage Ban.”

[10] Elicia Gonzales, “Declaration of Elicia Gonzales, LSW, M.Ed.,” 11 January 2019, https://www.womenslawproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Elicia-Gonzales-declaration-final.pdf.

[11] “National Bail Fund Network,” Community Justice Exchange, n.d., accessed 17 January 2019, https://www.communityjusticeexchange.org/national-bail-fund-network/.

[12] Nick Pinto, “The Bail Trap,” The New York Times, 13 August 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/magazine/the-bail-trap.html.

[13] Will Dobbie, Jacob Goldin, and Crystal S. Yang, “The Effects of Pretrial Detention on Conviction, Future Crime, and Employment: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges,” American Economic Review 108, no. 2 (2018): 225.

[14] Stephanie Wykstra, “Bail reform, which could save millions of unconvicted people from jail, explained,” Vox, 17 October 2018, https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2018/10/17/17955306/bail-reform-criminal-justice-inequality.

[15] “About Philadelphia Bail Watch,” Philadelphia Bail Fund, n.d., accessed 11 February 2019, https://www.phillybailfund.org/bailwatch/.

[16] Arjun Malik et al., Philadelphia Bail Watch Report: Findings and Recommendations Based on 611 Bail Hearings (The Philadelphia Bail Fund and Pennsylvanians for Modern Courts, 15 October 2018) [PDF file].

[17] “Abortion Funds 101,” National Network of Abortion Funds, n.d., accessed 11 February 2019, https://abortionfunds.org/abortion-funds-101/.

[18] Year-End Report 2018 (Chicago Community Bond Fund, November 2018) [PDF file].

[19] “About,” We Testify, n.d., accessed 27 January 2019, https://wetestify.org/about/.

[20] Kay Winston, “‘Roe v. Wade’ Must Include Abortion Access for Women in Prison,” Bitch Media, 22 January 2018, https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/roe-v-wade/abortion-in-prison.

[21] Yamani Hernandez (executive director, National Network of Abortion Funds), e-mail message to the author, 28 January 2019.

[22] Nan Kirkpatrick, “TEA Fund Supports the Black Mamas Bail Out in Dallas,” TEA Fund (blog), 3 May 2019, http://www.teafund.org/tea_fund_supports_the_black_mamas_bail_out_in_dallas.

[23] Hernandez.

[24] Elicia Gonzales (executive director, Women’s Medical Fund), interview with the author, 11 January 2019.