BY JENNIFER HELFRICH

I am an environmentalist. Friends call me a “tree hugger.” Tree huggers are a rare breed here at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). My fellow students each have their public policy area of focus—and the environment is not one of them.

I understand the dilemma; HKS students tend to exhaust themselves through over-commitment as it is, and no one can take on all issues. In this, the HKS student body mirrors a common approach: the environment often takes a back seat to other public policy concerns. Yet, I would argue that most public policy issues are inseparable from environmental policy. Unless we start thinking about this intersectionality, and developing strategies for tackling environmental and climate issues, we’re not going to be able to address pressing public health, inequality, and global hunger challenges.

Pollution is a public health problem. Globally, children who live near traffic are 89 percent more likely to have asthma and have stunted lung growth, with lungs that are 20 percent smaller than their peers. Annually, some 4.3 million premature deaths are caused by indoor air pollution among families who burn fuels in their homes to cook or for light. Reducing air pollution not only stems climate change, it is often synonymous with improving the lives of children and families who don’t have other options.

Pollution and climate change are also deeply connected to inequality—whether by income, race, or gender. Who do you think lives the closest to high traffic, smog prone areas like freeways and ports? In the US: poor communities of color. Much of the research on environmental pollution and health inequality reveals that it is low-income people of color who bear a disproportionate share of the health burden from exposure to environmental hazards. Minority populations are more likely to be co-located with pollution than white communities. Women’s reproductive health is particularly impacted: exposure to toxins has been identified as an explanation for why the children of women living in polluted areas (often low-income, often of color) tend to be underweight and experience developmental issues.

In developing countries, women bear the brunt of resource scarcity, as they are often responsible for providing food and water. Women and children spend the most time inside and are therefore the most impacted by indoor air pollution. Women are more exposed to and more susceptible to the adverse effects of environmental pollution. Climate change will have more of an effect on the tasks and responsibilities of women, increasing gender inequalities and raising the rate of female-specific harm.

The same goes for the world’s poor. The poorest countries will be the hardest hit by climate change, and those nearest the poverty line will likely fall below it, with hunger rates expected rise 10-20 percent by 2050.

Let me be clear: I understand that the environmental movement needs to do a better job considering socio-economic challenges. It is not uncommon that the benefits of sustainability accrue to the already privileged. There’s even a term for the displacement of low-income communities of color due to environmental improvements: environmental gentrification. Greening a neighborhood, improving transit, or making buildings more efficient can all raise costs and desirability, leading to gentrification. To avoid this, local governments need to increase community engagement and create strategies for protecting vulnerable communities—methods the environmental movement should be promoting.

As an environmentalist, I recognize that our work improving environmental outcomes and urban sustainability needs to consider parallel issues of poverty and historical injustice. Just as society cannot survive in a polluted environment, environmental sustainability is threatened in an unequal society.

As a student of public policy, I call on my peers and colleagues to consider how the environment intersects with their work. When President Trump systematically dismantles federal environmental protections, he’s not just attacking the environment. He’s attacking women and children, people of color, and low-income communities that live in polluted areas. When preventing climate change becomes secondary to development goals, it is the most vulnerable who will suffer.

The environment is not a niche issue. It is fundamentally intersectional. Making societies and economies more sustainable is not just about pollution, climate change or resource use, it is about gender and race, poverty and development, health and community. Our work should build on these connections; our future will be better for it.

Jennifer Helfrich is second year Master in Public Policy student at the Harvard Kennedy School, where she is Co-Director of the Energy and Environment Professional Interest Council. Jennifer’s focus is sustainable cities: how to balance environmental impact and resource use with growth and equality in urban systems.

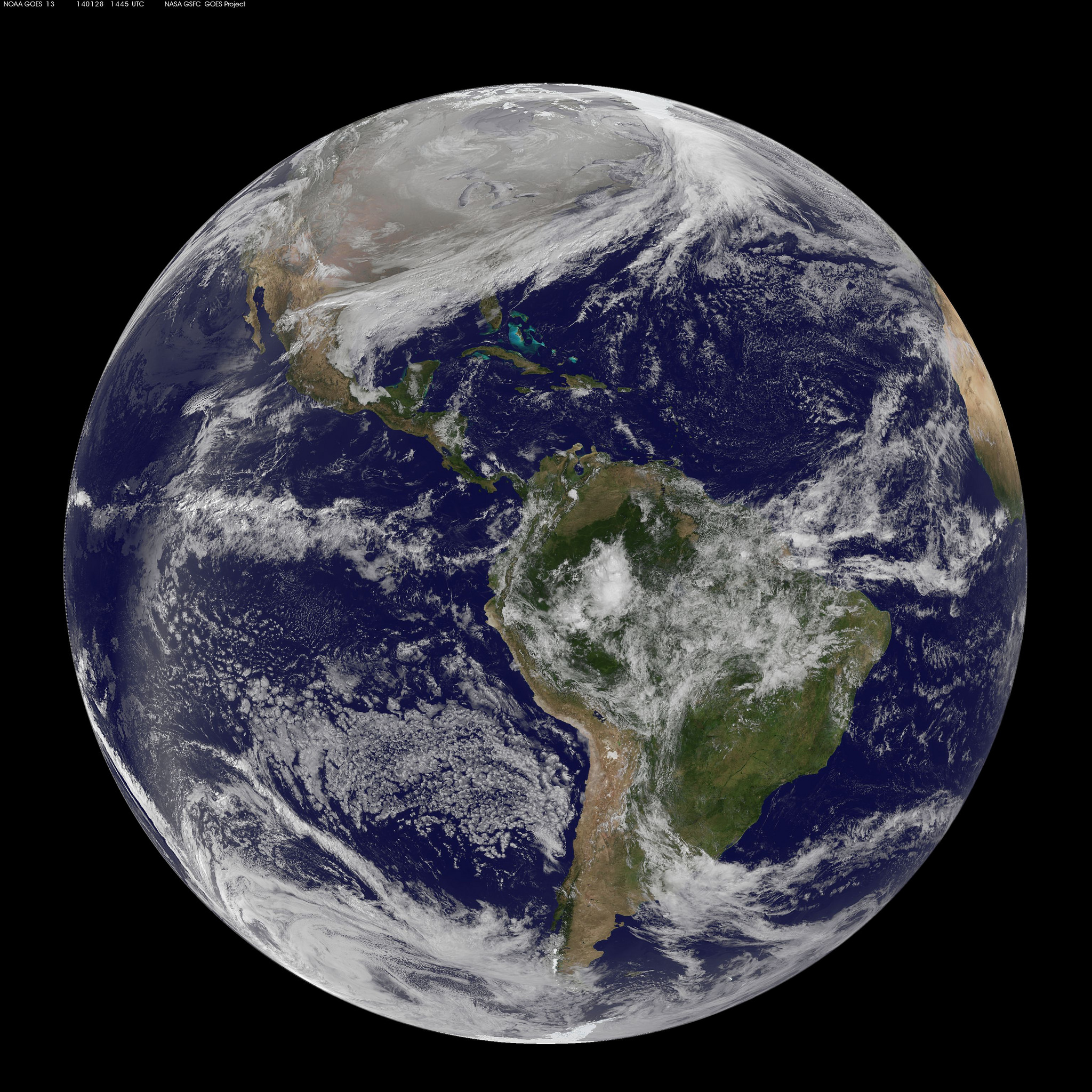

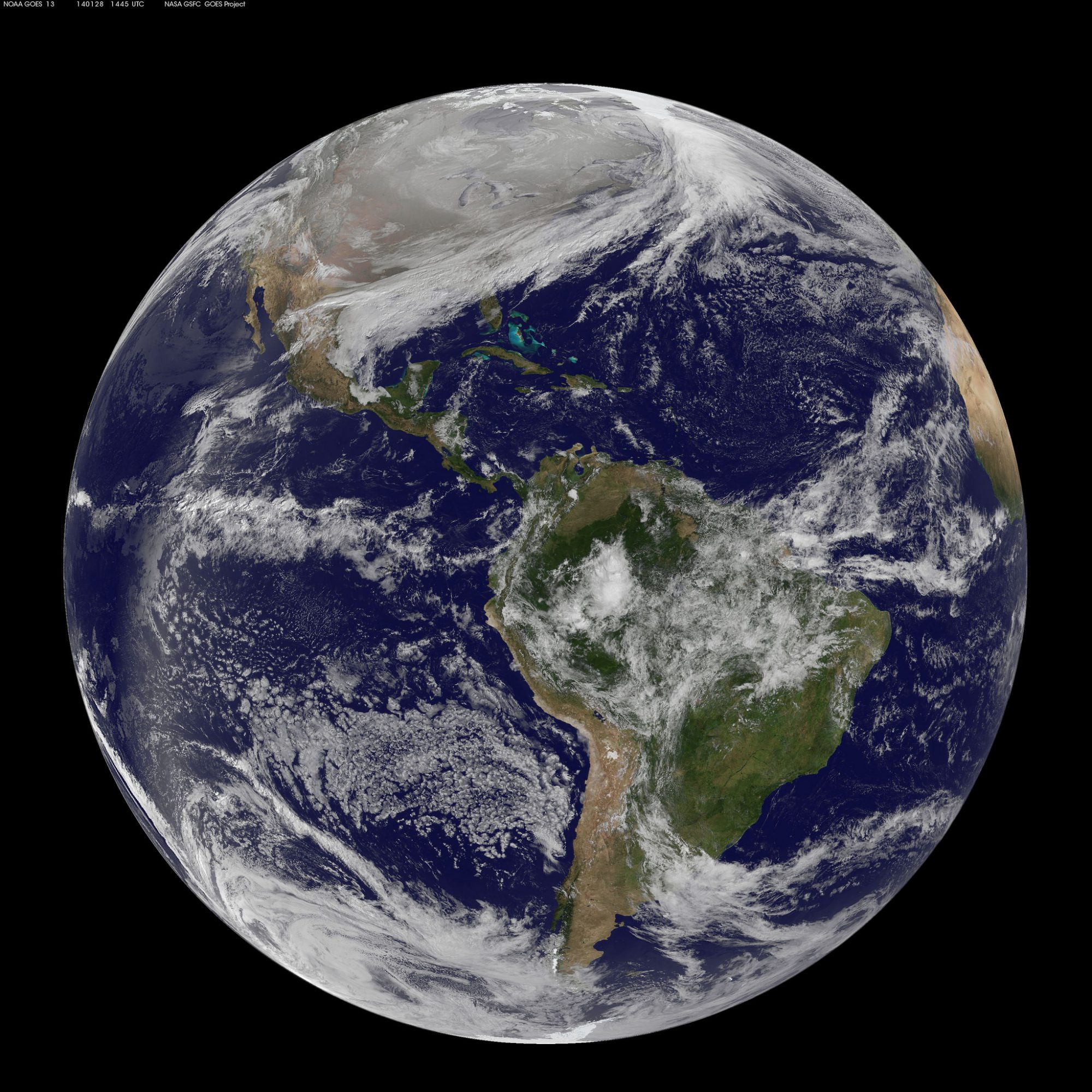

Photo Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight via Flickr