How the politicization of the debate over public education hurts the teaching profession.

BY ALEX MEADOW

Like many young adults, my twenties have featured family and friends asking me, “Alex, what are you up to now?” When I said that I was teaching, specifically at a school in a low-income neighborhood of Brooklyn, they would respond, “good for you,” often preceded by a sigh, followed by an admiring smile. I felt in their response a strange mix of pity and admiration, as if it were a sacrifice they wouldn’t make—to do such “good work” for so “little reward.” When I would alter my response to, “I’m in Teach for America (TFA),” the tone of many reactions changed into an exuberant “good for you!” I felt and heard praise associated with the exclusivity of the organization, the elite college graduates it recruits, and the altruistic purpose it serves.

These two versions of “good for you” led me to understand that public education in America has a fundamental problem of prestige. Teaching is not regarded as an elite career – as evidenced by inferior compensation, low barriers to entry, and low-quality graduate schools of education. Meanwhile, a formidable reform movement has arisen, fighting teachers’ unions on policies such as charter schools, vouchers, longer school day/year, merit-based pay for teachers, increased reliance on standardized testing, and abolishing teacher tenure, among other measures. Results have ranged from mixed to inconclusive, and quantitative and qualitative studies have been the subject of fierce debate (see Lucy Boyd’s recent blog post for KSR for more). However, neither the reformers nor the unions have been particularly effective in tackling the issue at the heart of the problem – prestige. Based on my experiences, I believe that the politicization of the education debate and intense focus by unions and reformers on controversial topics are doing more to hurt the teaching profession than to garner productive public attention towards it.

Hot topics like Common Core, standardized testing, teacher tenure, and charter schools have been the center of heated political debate; its semantics include “merit pay,” “accountability,” “aid,” and “due-process”. These terms make education sound more like a parole hearing than a potential career. During recent budget debates, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s spokeswoman went as far as to call failing schools in the state an “epidemic.” A report from the Center for American Progress shows how Common Core, formerly a bipartisan effort to raise standards, became a bitter political issue that led to decisions that were detrimental to students. This “politics effect” is best captured in polling that reveals 53% of those surveyed support Common Core, but 68% support the exact same national standards system when the name “Common Core” is withheld.

On the other side of the debate, unions cling to language of protection – fighting reformers on said “due-process” and tenure. During the budget debate in April, the president of the New York State United Teachers said that Governor Cuomo had “declared war on our profession and our union.” It isn’t difficult to see why many of the best and brightest young millennials steer clear of the teaching profession, one that is described by its own representatives as “at war” or “under attack.”

At the same time that the current teaching population is retiring in droves, this politicized debate has painted a picture of the teaching profession that is the absolute antithesis to the career that today’s young professionals are looking for. A recent PricewaterhouseCoopers study shows that “opportunities for personal development” and “the reputation of the organization” outweighed salary as factors that influenced millennials in job searches. Millennials seek progressive workplaces where they will be rewarded for hard work with reputation, flexibility, and opportunity for career advancement.

The problem of prestige in the teaching profession is not new. Long a majority female profession, teaching needed a strong union in the early-mid 20th century to secure protections like tenure and benefits to counteract pay discrimination based on gender. (This discrimination still exists today—women make 78 cents to a man’s dollar, and teachers are still grossly underpaid). Due to the many necessary and appropriate mid-century victories won by the unions, teaching made progress as a profession; it became known for strong protections, health, and retirement benefits, despite a persistently low salary, mediocre reputation, and very few opportunities for career advancement. These shortcomings should be the focus of reform, to better align the profession with young people’s interests. In the current political climate, however, they are only being exacerbated.

There are some practical innovations being implemented across the country focused on the professionalization of teaching. In Charlotte, N.C., a public-private partnership called Project L.I.F.T. (Leadership and Investment for Transformation) has invested in teachers’ career trajectories by creating an “Opportunity Culture” that allows multiple avenues for professional development and promotion. Through L.I.F.T, nine K-12 schools in the western Charlotte area have adopted reforms that include new teaching roles. The Multi-Classroom Leader, for example, is a highly effective teacher responsible for their own classroom and the management, training, and curricula of a small team of less-experienced teachers.

New avenues for promotion allow teachers play on their strengths; they can continue to teach in the classroom while maximizing time for management, collaboration, and professional development responsibilities. It is important to note that two years into Project L.I.F.T., staff turnover continues to be an issue in participating schools. Turning around a school’s culture takes time; patience on the part of policymakers is crucial when it comes to experimentation that may take years to generate outcomes.

Recruiting top talent is another strategy that Project L.I.F.T. and alternative certification programs such as TFA and New York City Teaching Fellows have implemented. According to McKinsey research, top-performing nations such as Singapore, South Korea, and Finland recruit teachers exclusively from the top-third of university graduates (defined by a composite of GPA, SAT and ACT scores). The U.S., in contrast, recruits most of its teachers from the bottom two-thirds of college classes, and for many schools in poor neighborhoods, from the bottom-third. McKinsey’s survey of over 900 top-third students and over 500 teachers from similar educational backgrounds also found that those surveyed viewed teaching as “unattractive in terms of the quality of the people in the field, professional growth and compensation.” TFA and others have been able to recruit these same top-third students not because of pay raises, but through efforts to professionalize, streamline and rebrand the profession.

In addition to alternative certification programs, increasing selectivity for traditional graduate programs is another proven reform targeting the prestige problem. In 1979, Finland shifted all of its teacher preparation from teacher’s colleges to elite universities. Today, teaching is the most popular profession in that country for the young – in 2010, 6,600 college graduates competed for just 660 spots in Finnish teacher training programs. The State University of New York (SUNY) schools of education all raised their admissions requirements in 2013 – however, most U.S. states’ barriers to entry remain shockingly low. Country-to-country comparisons have their limitations. Nevertheless, increasing standards for admission to schools of education is a replicable, low-cost tool that has worked in Finland and deserves attention in the U.S.

The trends and innovations in the way we recruit, retain, and reward our teachers have generated encouragement and concern, depending on how one interprets them. Initiatives like TFA, Project L.I.F.T. and the like have attracted private philanthropy to K-12 education at a staggering rate. A recent report from the Journal Education Researcher shows that charitable giving to K-12 programs grew 70% between 2000 and 2010. On the other hand, unions and other opponents have pushed to rein in “privatization” efforts of this kind, concerned about their scalability, and potential long-term adverse effects on the education system.

In my opinion, increased attention to public education from college graduates, donors, and the general public is an important, positive step in changing the story of teaching in this country. Questions certainly remain about the scalability of privately funded initiatives, and around the retention of the top-third of graduates that are now entering the profession. Prestige is also, of course, not the only problem with American education: systemic poverty, racism, health, and housing remain huge ones as well. However, the prestige problem is one that can be addressed with evidence-backed, low-cost policies and innovations like those discussed above. Leaders in public education can and should draw from these initiatives in order to reshape the teaching profession to better fit the reality of the workforce and the world surrounding it today. Acknowledging shared responsibility for the politicization of the debate and taking small steps to implement policy changes would be a good start toward a new framing of education careers, one that always elicits an emphatic “good for you!”

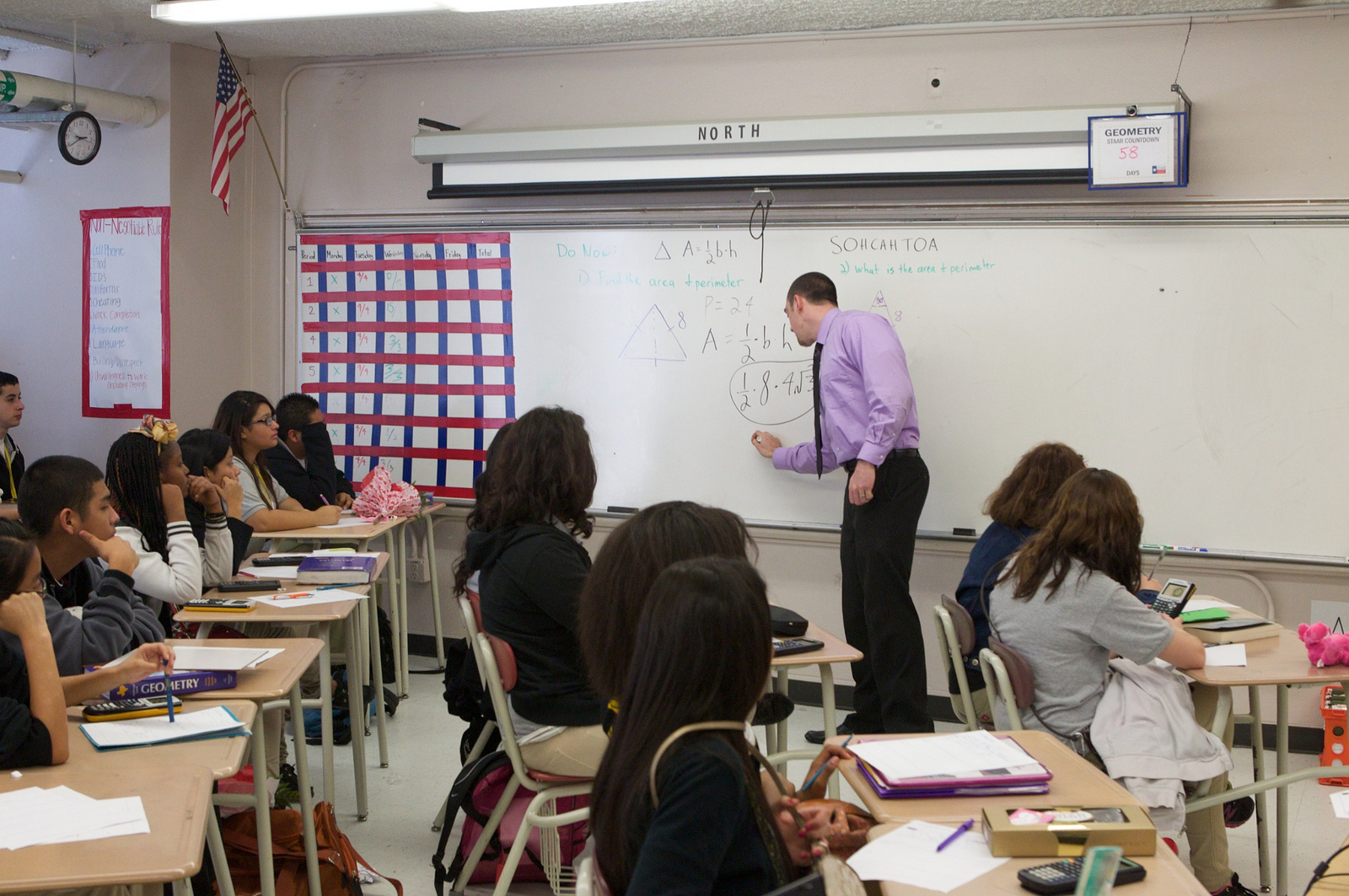

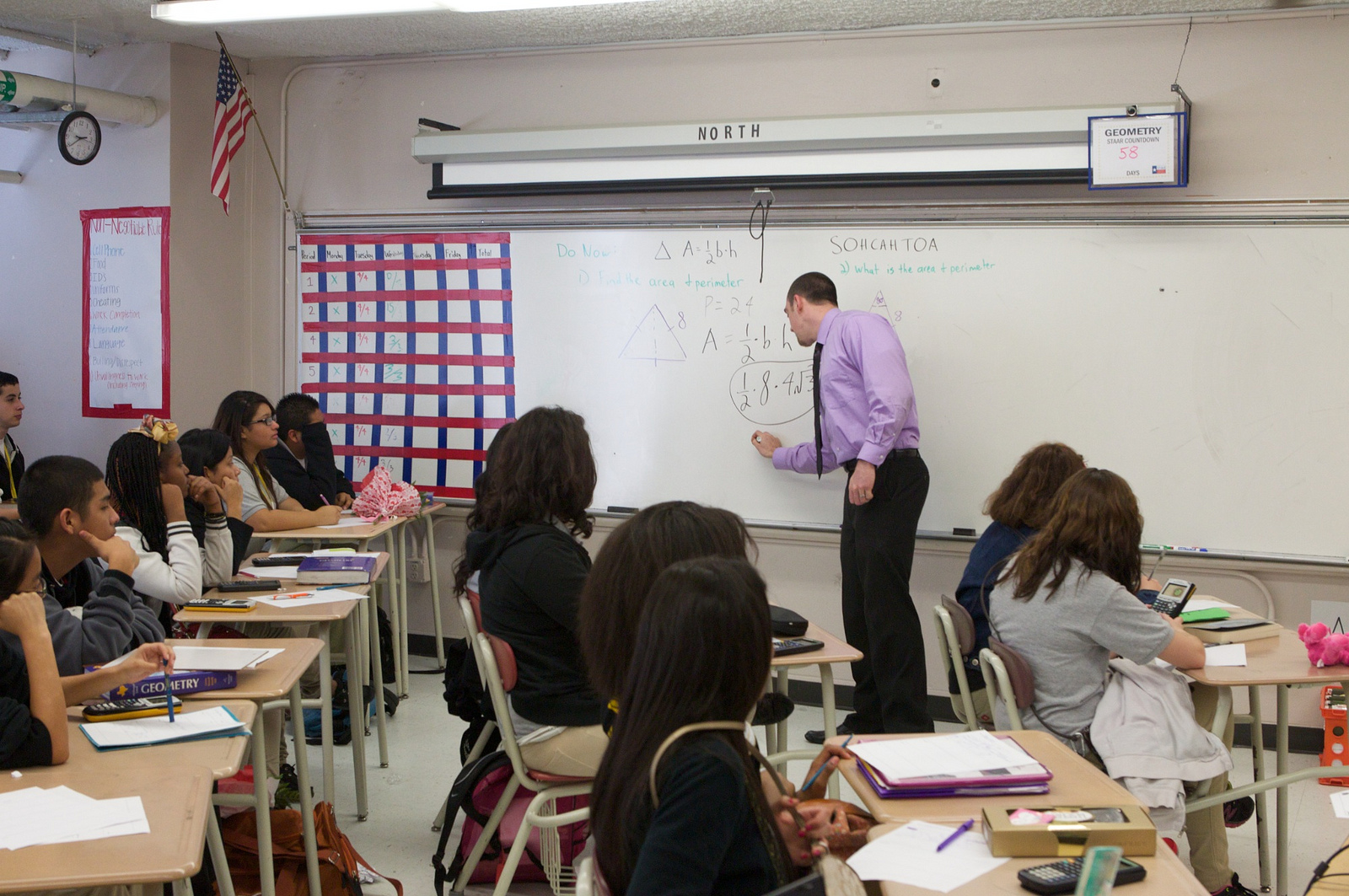

Photo credit: US Department of Education