BY JANE ZHU AND IAN METZLER

Susan Tomkins will graduate from Harvard Medical School in May 2012 with $196,000 in loans. As a first-year student she had hoped to carry her father’s worn black medical bag into the rural Oregon community where she was born. But faced with the burden of high debt—totaling nearly $500,000 over twenty to thirty years when interest is included—Susan reluctantly eliminated every primary care specialty from her career plans. She recently chose to pursue dermatology, a specialty that commands nearly double the salary of family care physicians. “I didn’t expect to have to worry about the economics of it all,” she explains. “But the harsh reality is that I have to choose between relieving my family from an enormous debt and pursuing a greater good in my small hometown. As is, I’ll be paying my debts until my forties or fifties.”

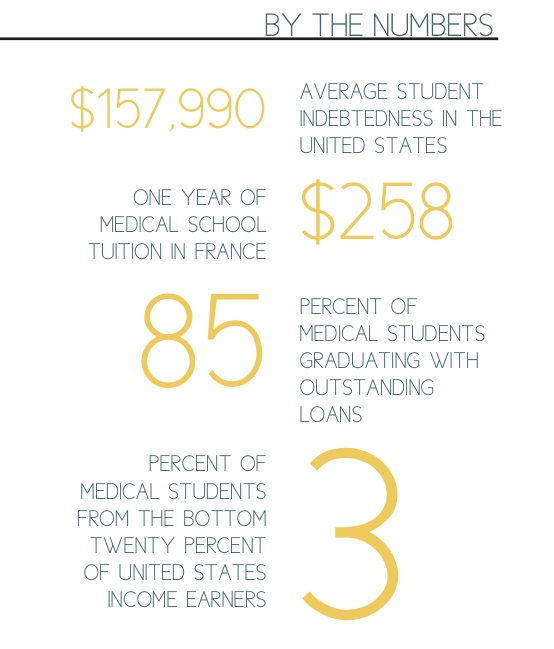

A composite of three real-life medical students, “Susan” illustrates the kinds of choices that all too many aspiring doctors face today. As education costs grow larger than most people’s personal resources, more students are going into debt to finance their degrees; in fact, more than 85 percent of medical students now graduate with outstanding loans. Average student indebtedness is $157,990, with nearly 80 percent of graduates owing at least $100,000. Just two decades ago, indebtedness averaged $27,000 (American Medical Association n.d.). Physicians’ incomes have increased much more slowly during the same period— and even more slowly than consumer prices—making it more difficult for doctors to repay their educational loans today than ever before.

This trend is costly not only for new generations of doctors but also for American society. For one thing, it will deprive us of a critical presence in our medical ranks: doctors from low-income and ethnic minority backgrounds. One of our most pressing health care challenges is the need for a more diverse physician workforce to serve an increasingly racially and socioeconomically diverse population. By 2050, more than half of the U.S. population will be racial and ethnic minorities (Association of American Medical Colleges n.d.), and as the recent Occupy protests have reminded us, the income gap continues to widen. It is no wonder that the Association of American Medical Colleges and many other physician organizations have called for increased diversity in medicine as a way to improve access to health care for the underserved.

But it is unlikely that these communities will be fully served without reforming who we educate to become doctors. The evidence is clear: minority physicians are more likely than White doctors to practice in low-income and minority communities. When it comes to underserved communities, a diverse workforce builds better patient-doctor relationships, increases patient satisfaction, and encourages more culturally competent care (Association of American Medical Colleges n.d.). But despite there being two applicants for every medical school spot, cost remains the strongest deterrent for minority and low-income students considering a medical degree, and these groups remain severely underrepresented in medicine (Jolly 2005). Only one in ten graduating MDs is Black, Hispanic, or Native American; just 3 percent of medical students are from households in the bottom 20 percent of U.S. income earners. Meanwhile, more than half of all medical students come from families in the top 20 percent (Greysen et al. 2011). If the current rate of debt continues, there may come a time when only the elite can finance a medical education. Millions of Americans will suffer as a result.

The specter of debt also profoundly influences postgraduate career choices and discourages future doctors from entering primary care. Primary care has always been the foundation of our health care system, allowing doctors to establish long-term relationships with patients and to ensure coordination of care. But nearly one in five Americans today does not have access to primary care due to a shortage of nearly 30,000 primary care physicians (Cullen et al. 2011). This shortage exacerbates the fragmented care, inappropriate use of specialists, and skyrocketing health care costs that are exhausting our current system.

Consider the choice facing medical school graduates: in 2010, a primary care physician earned a median salary of $159,000 while radiologists earned more than double this amount (Guglielmo 2011). While these earnings may appear high, primary care no longer compensates doctors enough to cover the costs of running a clinic, malpractice insurance, and paying off debts from school. To make ends meet, primary care physicians either must take on more patients and risk the quality of care provided, or they must exclude publicly insured patients altogether. Not surprisingly, as average indebtedness has risen, the number of applicants to primary care residencies has shrunk. For every one-hundred medical school students who graduate next year, only seven will go into general internal medicine or family practice. This diminished interest in primary care means that we cannot possibly meet our current shortage of primary care doctors, which is expected to increase exponentially as retiring baby boomers begin to flood the health care system.

What to Do About It

A comprehensive solution to our broken health care system must include financial reform for medical education. But instead of decreasing the debt burden at its roots, the federal government has addressed the issue primarily with loan-repayment programs. The National Health Services Corps helps doctors repay their loans in exchange for work in underserved areas. Less than 4,000 clinicians currently participate, and this number includes nurses, counselors, dentists, and other health care personnel. States like Kansas, Arkansas, and Texas have loan-forgiveness programs in exchange for commitments to return to designated in-state areas upon graduation, but these programs are small and do little to shift the larger cost trends (Schick 2011). To add to these options, the 2010 Affordable Care Act capped monthly loan repayments based on income, reducing a typical monthly payment from $2,000 to about $400 (Schick 2011). These programs are commendable but insufficient. They occur too late in the education process to effectively recruit underrepresented minorities during college or to affect specialty choices for graduating medical students. And recent legislation has only compounded the problem. With the 2011 Budget Control Act, Congress removed subsidies from federal Stafford loans for all graduate and professional school students. Effective July 2012, medical students will begin accruing more interest on their already bulky loans, directly undermining the intended benefits of federal loan-forgiveness programs (U.S. House of Representatives 2011).

These initiatives are Band-Aid solutions to the student debt crisis, but the medical education system needs a cure. Rather than address skyrocketing debt after the fact, we should reduce student loan needs from the start, a crucial step that the Obama administration has already applied to the undergraduate student debt crisis (Nakamura and de Vise 2012). The president recently announced a plan that would make federal aid contingent upon college affordability; as efforts move forward to alleviate the undergraduate debt burden, we have a rare opportunity to address medical school debt simultaneously. By reducing the cost of medical education, medical students will have incentives to assume a wider range of socially responsible roles. In almost every other country, the costs of medical education are substantially lower. Medical school tuition in France costs less than $258 annually, with almost all expenditures financed by the state. In Canada, medical tuition ranges from $6,000 to $16,000, with partial funding from the government, private resources, and redirected clinical earnings (Segouin and Hodges 2005).

These numbers compel us to ask: how much should we pay to train physicians, and does more spending necessarily produce higher value in medical education? Our current health care reform efforts have given us an opportunity to reevaluate our runaway health care expenditures and eliminate an estimated $1.3 trillion in annual waste. Money saved from improved efficiency could be reinvested into medical education, not through loan-forgiveness programs but as tuition caps for individual medical schools and grants for minority and low-income students. In the face of our mounting federal debt, we also ought to eliminate the up-front costs of medical school and allow physicians to redirect a nominal percentage of their earnings back to the system over ten to twenty years. This strategy is self-sustaining and requires little long-term financial support from the federal government. Most importantly, it would remove the economic constraints that currently discourage diversity in medicine and push students out of primary care. If our current system continues, one thing is clear: the medical profession—and the health of our communities—will soon become crippled by the growing weight of unmanageable debt.

References

American Medical Association. n.d. Medical student debt: Background.

Association of American Medical Colleges. n.d. America needs a more diverse physician workforce. AspiringDocs.org.

Cullen, Esme, Usha Ranji, and Alina Salganicoff. 2011. Primary care shortage. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Greysen, Ryan S., Candice Chen, and Fitzhugh Mullan. 2011. A history of medical student debt: Observations and implications for the future of medical education. Academic Medicine 86(7): 840-845.

Guglielmo, Wayne. 2011. Physician compensation report 2011. Medscape.

Jolly, Paul. 2005. Medical school tuition and young physicians’ indebtedness. HealthAffairs (Millwood) 24(2): 527-535.

Nakamura, David, and Daniel de Vise. 2012. Obama outlines incentive plan to rein in college tuition costs. Washington Post, 27 January.

Segouin, Christophe, and Brian Hodges. 2005. Educating doctors in France and Canada: Are the differences based on evidence or history? Medical Education 39(12): 1205-1212.

Shick, Matthew. 2011. Student loan repayment. Association of American Medical Colleges.

U.S. House of Representatives. 2011. Sectional summary of the Budget Control Act of 2011. House of Representatives Committee on Rules, 112th Congress, 25 July.

This article was originally published in the 2012 edition of the Kennedy School Review.

Jane Zhu is a dual-degree MD/Master in Public Policy student at Harvard Medical School and the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. She is interested in health care access, health insurance, and racial and ethnic disparities related to health care reform.

Ian Metzler is a student at Harvard Medical School studying health systems improvement and health care policy at Children’s Hospital Boston.

Image source here.