After a tumultuous August in Washington, one thing is certain: the Trump Administration will amend the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). President Trump met with Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto at the July 7th G20 Summit, where each expressed a desire to conclude any NAFTA discussion by year-end. According to a White House statement after the encounter, the President suggested a “total renegotiation” of the pact, which he has famously and frequently called a “disaster.” The White House then announced in late July that renegotiation was set to begin on August 16th—a golden opportunity to consider both the economic and labor updates demanded by the aging trade document. In particular, any renewed discussion of NAFTA must also include a critical assessment of the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC) and its untapped potential to bolster transnational labor protection.

NAALC has been a source of both hope and frustration from the outset. Though singular as the first labor accord attached to a preferential trade agreement, it was weak by design and separate from the primary trade agreement text. It meant to protect Mexican, Canadian, and American labor by guaranteeing the basic freedom to associate, unionize, and earn a fair wage. Ultimately, it was undercut by concern from business in both Mexico and the United States that it would increase wages at the Mexican maquila (factory) and that inexpensive, tariff-free raw imports to Mexico would halt. On its face, it set forth a complex enforcement mechanism to prevent labor abuse. Yet, NAALC failed to meet its mandate amongst concern that it might undercut one of the principle economic boons of NAFTA—cheap labor across the border used to assemble and export finished inventory.

Meanwhile, American labor leaders challenged the notion that NAALC would foster any growth in wages or improve labor protections. Indeed, it was largely an afterthought. Not until after NAFTA had been signed (in 1992) did then-candidate Bill Clinton, seeking the endorsement of the AFL-CIO, double down on his commitment to labor protection. At the close of negotiation, the NAALC enforcement mechanism was whittled to its current skeletal form. It walked a fine line to appease corporatist Mexican labor, but largely neglected American labor—which launched protest campaigns such as “Not My NAFTA” — and grappled with the political demand of uniting three distinct nations under a flagship labor document without jeopardizing close economic partnership. Yet, it was adopted.

A weak, political, and largely ineffective NAALC remained. It mandated that states enforce International Labor Organization (ILO) and domestic labor law, without setting minimum standards on either. It lacked a transnational body to monitor state behavior, but created National Administrative Offices (NAOs) couched within the complex bureaucracy of each domestic labor department to accept and review cases. Because each state could independently interpret the accord, confusion—and inaction— became the norm.

An NAO can request a public hearing or Ministerial Consultation on labor abuse, but cannot hear witness testimony. A violation can result in a Ministerial Declaration or Report of Review, neither of which possess teeth. The second tier of the mechanism—the Evaluation Committee of Experts (ECE)—has slightly more authority to investigate, yet also cannot compel meaningful action. Only the final Arbitral Panel (AP) can sanction, but only with a small fine or a brief suspension from a narrow slice of trade. Further, the most frequently abused of the protection clauses in NAALC—the right to strike, to organize, and to collectively bargaining—cannot be enforced by an AP. The right to associate is the most violated NAALC principle in Mexico. No NAFTA member has been indicted by an ECE or AP yet.

One need only peruse the list of NAO cases brought in the last two decades to appreciate NAALC’s shortcomings. In 2003, United Students Against Sweatshops successfully obtained a Ministerial Consultation for a garment worker complaint, but received the final Report of Review half a decade later. In the 2001 Duro Bag case, Mexico refused to submit an NAO complaint about curtailed collective bargaining and forced spoken ballots at the Duro Bag Company. The United States NAO refused to review the case when it was later brought by the AFL-CIO—a pass on unlawful union protocol at an American business abroad. Only 39 cases have been brought under NAALC since its implementation, nine of which were declined for review.

Abuse of NAALC has a dire effect, especially for the most vulnerable. Women in Mexico have faced a unique struggle for redress, most notably in Ciudad Juarez. In 1997, Human Rights Watch, the International Labor Rights Fund, and Mexico’s National Association of Democratic Lawyers brought U.S. NAO Case No. 9701, which accused Mexico of failing to protect women released from maquila jobs for being pregnant and failure to stop the routine administration of pregnancy tests as a condition for employment. The result was a report by the United States NAO that criticized the pressure put on pregnant women to leave, but neglected to address pre-employment tests. Additional scholarship has connected the infamous Ciudad Juarez femicidios—brutal waves of gender-based violence against women in Juarez maquilas in the late 20th century, and as recently as 2010—to conditions exacerbated by cross-border trade.

In March, a draft letter from the Acting United States Trade Representative provided some insight into how the Trump Administration may address transnational labor protection. For instance, NAFTA text may include labor language, and may draw on key language from the ghost of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Yet even such language, noted Assistant Professor of International Relations at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas in Mexico and Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars expert Kimberly A. Nolan Garcia, may not adequately protect rights not explicit in the 1998 ILO Declaration: the right to equal pay for women, the right to labor protection in migration, and the right to safety from occupational hazard and harassment.

Strong , cross-border labor protection makes social and economic sense, and is in the interest of all who desire a sustained, actionable commitment to mobility and basic freedom for all—not to mention a more secure border. If we are to affirm our commitment to the vulnerable Mexican and the American worker alike, NAALC must be subject to further scrutiny. If not now, when?

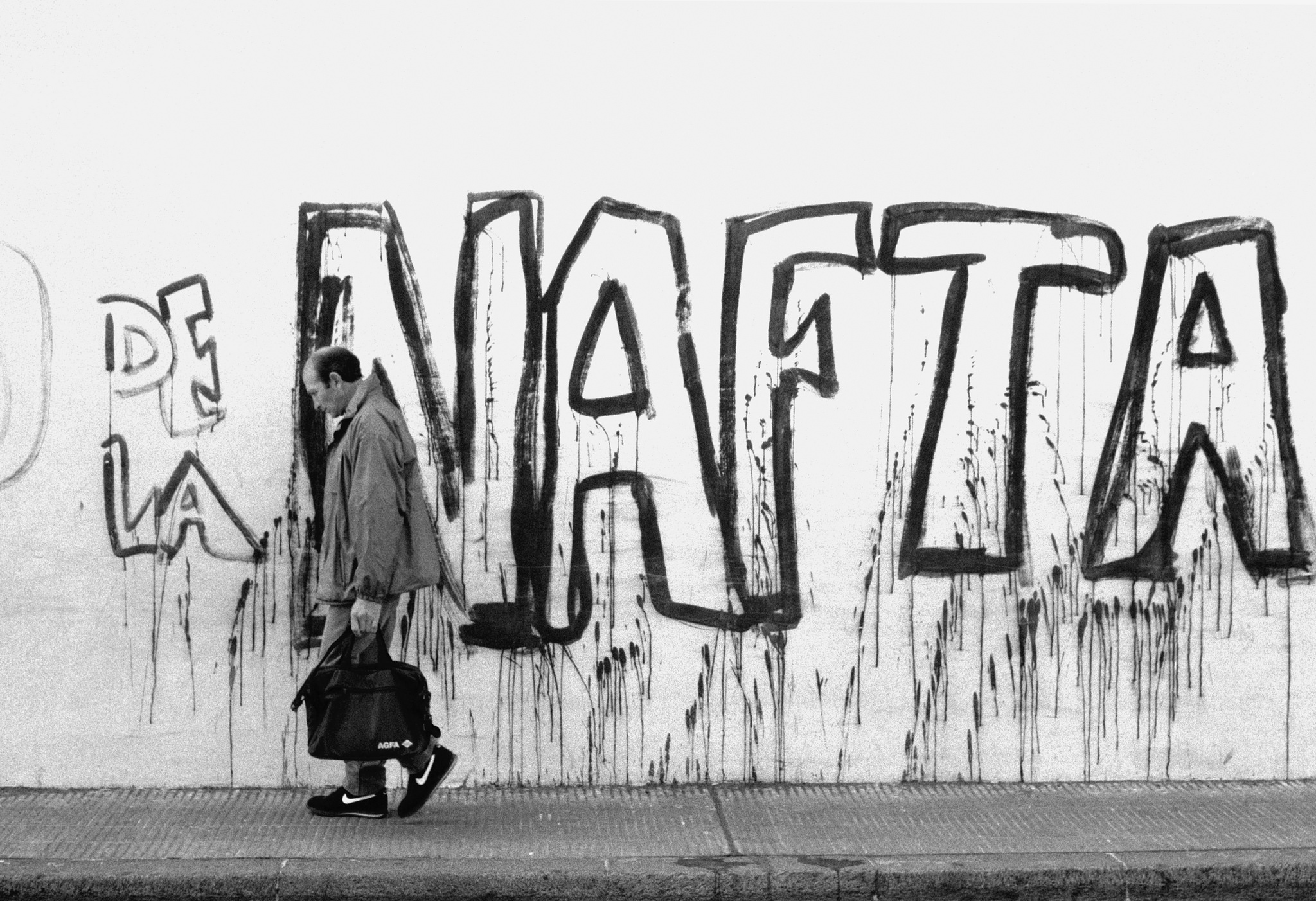

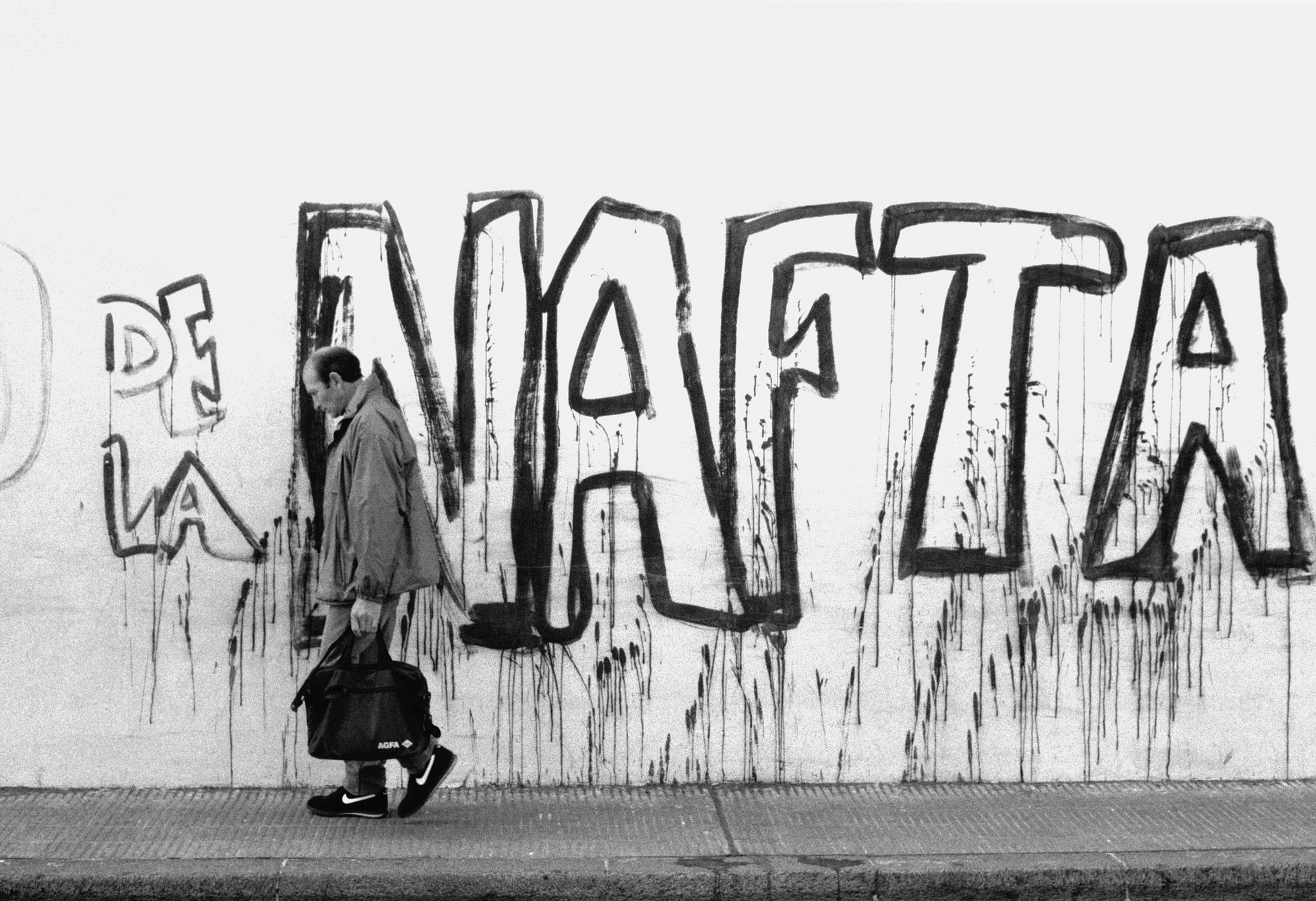

Photo Credit: Woody Wood via Flickr

Edited by James Pagano