Francis Garcia walked into work at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas one morning in late 2007. A migrant from Honduras, Garcia had crossed through Mexico after Hurricane Mitch devastated her country, leaving almost one million Hondurans homeless. She joined the Grand as a housekeeper earning $14.50 an hour; far more than she could expect to earn at home. Yet Garcia’s wage is also comparatively higher than wages in similar professions elsewhere in the United States. The reason: Garcia is a member of Nevada’s Culinary Union (‘the Culinary’), the organizing powerhouse that has transformed employment in Las Vegas’s hotels and catering industries. Garcia’s contract, negotiated by the Culinary, guarantees 40 hours of work per week. As a result, she earns almost $800 weekly—compared to the $330 that many other non-unionized housekeepers earn—with a pension plan, stellar health coverage, and an innovative scheme to help union members save for a home deposit.[1]

The Culinary has seen its membership triple since the 1980s, in large part due to a dual strategy of training rank and file workers to become union leaders and advocating for change with political leaders. The union was a major driver of grassroots support in the run up to the 2016 election: union members and supporters spoke to 75,000 voters, registered 8,000 people to vote, and got 54,000 early voters to the polls. Its early work led the Washington Post to describe the Culinary as the “dominant political force in the state.” The Culinary’s political director Yvanna Cancela puts its success down to two factors: the benefits it delivers to members and the strong link between workers and shop stewards within the Vegas hotels. The Culinary prides itself on organizing around issues that affect members’ lives rather than the personality of candidates.

Though unions like the Culinary still aren’t commonplace, they’re the type of grassroots organizing machines that former New York Times labor correspondent, Steven Greenhouse, believes could be the future for American labor. In his new book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor, Greenhouse expertly charts the fate of the American worker, breaking the vast span of US labor history into bite size chunks. He takes readers from the New York Triangle Factory Fire in 1911—one of the country’s most devastating workplace disasters—in which almost 150 people lost their lives, to the progressive worker-employer coalitions in place today at healthcare giant Kaiser Permanente. He follows the leaders of the labor movement as they strengthened the rights of American workers: Frances Perkins, who steered President Franklin D. Roosevelt to include ambitious pro-worker policies in the New Deal, and Detroit organizer Walter Reuther, who campaigned to raise auto-workers to America’s new middle class, receive particular attention.

Yet Greenhouse doesn’t paint a wholly positive picture of American labor. His retelling of the infamous air-traffic controllers’ strike under President Ronald Reagan highlights the role that union leaders played in their own downfall. In 1981 Reagan fired 11,000 air traffic controllers for failing to return to work during a strike over working conditions and pay. The union sought a $770m package of improvements to their contract’s terms and conditions: a $10,000 wage increase per worker and a reduction in working hours from 40 to 32 hours per week. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) countered with a $40m package which was quickly rejected by the union. Labor leaders held out, managing to ground 7,000 flights in a single day at the height of the strike. Even as the government brought in replacements from the military to replace striking workers, union bosses hoped the strike would force the hand of the FAA, and lead to a generous package being agreed for their members. Having made his opposition to the air-traffic controllers a highly public political issue, Reagan’s final blow came in imposing a lifetime ban on rehiring workers who engaged in strike action. For Greenhouse, this act marked the start of the anti-union tenor that was to carry for the majority of the 1980s and 1990s. Combined with economic liberalization, this moment, argues Greenhouse, was the point at which the US economy began to turn its back on workers. Yet Greenhouse also doesn’t shy away from the fact that, as with the air-traffic controllers, the leaders of organized labor have, at times, failed to recognize when their chances of success were diminishing. Instead, hope remained their primary strategy.

Over 40 years out from labor’s heyday, Greenhouse now warns that with the deep opposition to unions in much of corporate America, there’s a real risk that as fewer Americans know about organized labor’s achievements. With overall union membership declining from 35 per cent in 1954 to 10.5 per cent in 2018, unions face “longer and longer odds” to rebuild their membership base. Indeed, even Democratic Presidents have failed to reform labor laws and give a boost to those organizing workers’ rights. Most recently Obama vowed to enact legislation that would force employers and unions into arbitration if no contract was reached within 120 days of a negotiation, to avoid companies stonewalling labor negotiations. Yet this was shelved until the administration had pushed through healthcare reform and was never revived.

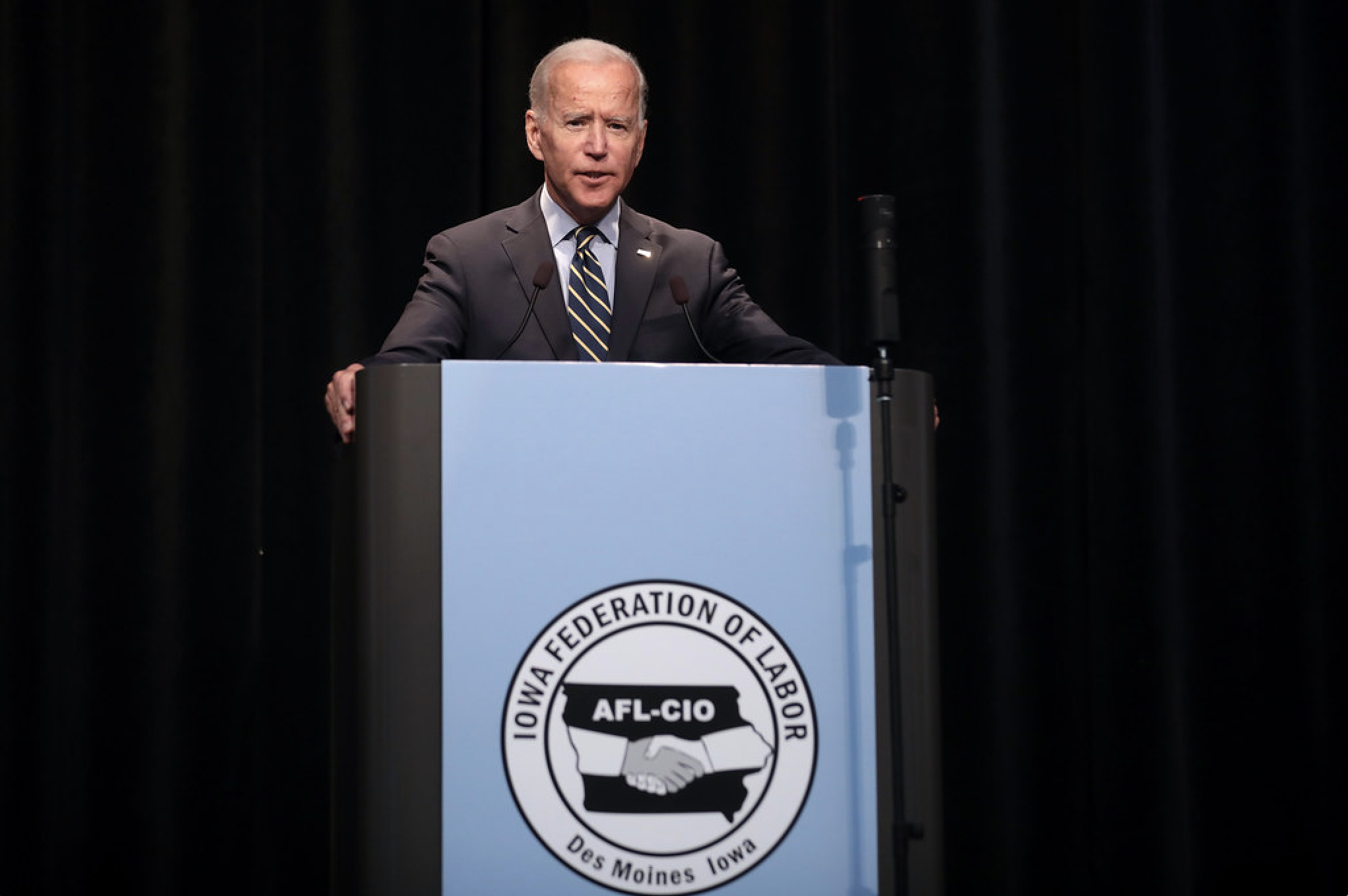

In the early 1970s former adviser to Robert Kennedy, Charles Guggenheim advised then presidential candidate George McGovern: “The necessity to turn your concerns to the ‘forgotten man in America’ cannot be overemphasized.” Five decades on, this advice could be given to today’s Presidential candidates as they seek to rebuild Democratic support in blue-collar America. For the candidates vying for the Democratic nomination, just weeks out from the Super Tuesday, most are digging deep to be seen as a friend to organized labor. A $15 minimum wage, paid parental leave, and paid sick leave are now a common Democratic policy platform. There’s major support for repealing Taft-Hartley, the infamous 1947 labor law that critics argue enables non-union members to benefit from the concessions achieved by union representatives. And some candidates are pushing for a more ambitious agenda. Elizabeth Warren has spoken in favor of worker representatives on company boards; a common approach to building employee-employer partnerships in Germany. Both Joe Biden and Amy Klobuchar support the introduction of a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, to protect domestic workers who were previously excluded from workplace protections.

Although these measures would help restore strength to labor, Greenhouse invites us to look for more fundamental solutions to strengthen the political power of workers. He nods to campaign finance reform as the most direct route to ensuring big politics acts in the best interests of ordinary citizens. He cites innovative approaches like Seattle’s ‘democracy vouchers’—which gives each voter $25 to donate to the campaigns of city council candidates—as a model that could be extended to Presidential, Senate, and House races. In Greenhouse’s view, measures like this will go some way towards ensuring that representatives are elected based on genuine local support, rather than their ability to fundraise. Without this, he argues, big money—and its interests—will continue to dominate politics and, by extension, the rights afforded to organized labor.

Beaten Down, Worked Up is an essential read for those seeking to improve conditions and economic opportunity for American workers. Greenhouse’s skill lies in showing that trade unionism isn’t a relic of an old, more naïve, form of American capitalism. In an economy where an increasing number of people have close to little influence over their conditions at work, Greenhouse argues persuasively for the power of unions in rebuilding dignity and agency for American workers. As we approach November 2020, all eyes will be on the Democratic frontrunners to see how central labor really is to their vision for a fairer, more prosperous America.

Edited by: Christie Lawrence

Photo by: Wikimedia

[1] Greenhouse, Steven. 2019. Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present and Future of American Labor. New York, NY: Knopf, https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/246798/beaten-down-worked-up-by-steven-greenhouse/ The data and statistics included in this piece are drawn from Greenhouse’s research, with full citations included in the original source document.