Moving towards minority government: a global view of Australia’s upcoming election

Key takeaways

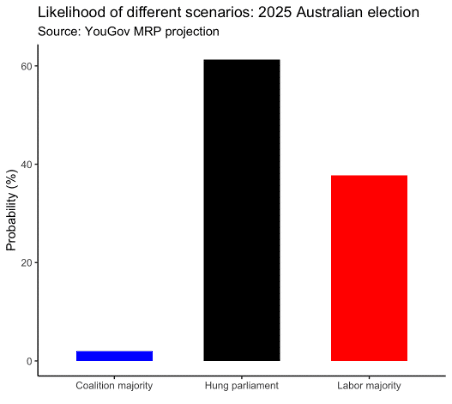

- Australia’s upcoming election has a more than 60% chance of ending in minority government, reflecting a broader global trend of major parties losing popularity.

- Because the social changes that have driven this trend are likely to persist, major parties must consider how to best manage the rise of smaller political forces.

- Australia typifies these structural changes; for this reason, political observers should pay attention to the rise of Australia’s “teals” (and how major parties respond to them).

On May 3, Australians will head to the polls to deliver their verdict on the first-term Albanese Labor government. While the campaign is still well underway, forecasters give a more than 60% chance that Australia will face no party winning a majority in the House of Representatives, likely leading to a minority government.[i]

Australia has a ‘Washminster’ system, where Westminster parliamentary conventions and a Prime Minister meet Washington’s federal constitutionalism and a powerful Senate. If no party gains a majority in the House of Representatives, party leaders must negotiate with crossbench MPs to form a minority government and appoint a PM. If this eventuates, it will repeat Australia’s experience of minority government 15 years ago.

Such a prospect represents an increasingly global and equally substantial challenge for major parties and, perhaps, legislative effectiveness. While major parties could once be expected to comfortably form majority government, this paradigm is evaporating. Now, the specter of minority government will demand compromises and new alliances across an increasingly fragmented legislature.

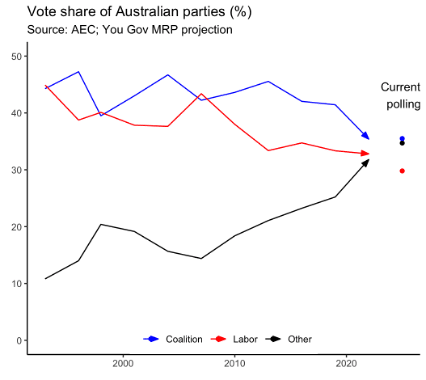

Behind this new reality lies a rise of minor parties in a country long dominated by Labor or the Coalition.[ii] Since 2013, the number of independents elected to Australia’s 151 seat lower house has more than tripled from five to 16, with drivers including increasingly dissatisfied centrist voters and more professionalized operations.[iii] The share of electorates where the winner received over 50% of the primary vote has decreased from ~60% in 2004 to less than 10% in 2022.[iv] And if forecasts of the incumbent Labor government winning less than 30% of the primary vote come to bear, the party would face its lowest vote in 70 years.

Major Parties Have Declined Globally Too

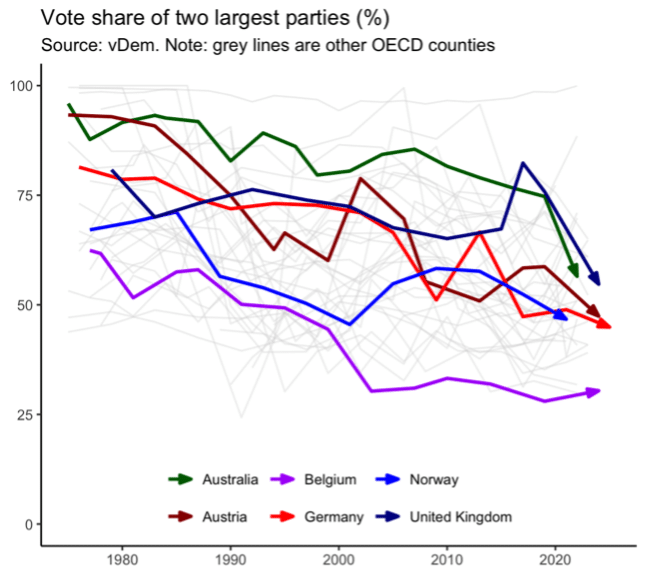

The possibility of minority government in Australia is perhaps unsurprising from a global perspective. Across a range of western democracies, major parties have seen a dropping vote share. In the United Kingdom, what appeared to be a resounding victory for Labour masked an historically low vote share of 33% (with the newly formed Reform UK winning 14%). In Germany’s 2025 election, the center-left SDP’s vote share fell to 16% (off its peak of 41% in 1998), behind the far-right AFD, which received 21% of the popular vote.

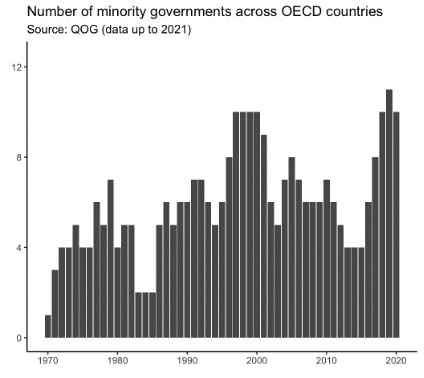

And this has translated to the increasing formation of minority governments. Over ten years, the number of minority governments in the OECD nearly doubled from 6 in 2010 to 11 in 2020.[v] Notable recent examples include Germany’s red-green coalition, Norway’s Støre Cabinet, and, more recently, Austria’s three-party coalition. In each of these instances, major parties had to partner more closely with increasingly dominant minor players to support stable government. For some, this has meant grappling with the ethics of partnering with far-right parties (e.g., Belgium’s major parties facing the choice of working with the electorally ascendent Vlaams Belang). When leaders rule out working with far-right parties, they limit their options for governing. Belgium took over 400 days to establish its ‘Arizona’ coalition government; Austria took five months to form government in a way that excluded the far right.[vi]

Reeling from the reckoning that incumbents faced in 2024, it would be easy to say that economic frustration driven by the cost-of-living crisis has caused this shift. And that’s true, in part: shifts away from incumbent government in Germany and the UK indeed broke heavily for once minor parties. But incumbent backlash doesn’t explain it all.

Sidebar: Dimensions of how minority governments differ from majority government

| Dimension | Effects that it can have | Expected effect in Australia |

| Shift in policy focus | Shifts government’s priorities to midpoint of coalition partners (either centrist or extremist) | Emphasis on voters in the center |

| Speed of passing legislation | Legislation takes more time to draft before it is tabled; less debate occurs once tabled | Time to pass will increase and/or number of staffers for crossbench will increase (if crossbench is not in government[vii]) |

| Stability of Government | Increase in likelihood of government collapse | Likelihood of completing full parliamentary term unchanged |

| Recurrence of minority government | Can either reinforce or dampen trends that led to minority government | Will dampen drivers of minority government, increasing likelihood of majority government in next term |

| Legitimacy of minor parties | Minor parties can be associated with the ‘establishment’; alternatively, extreme parties can be legitimized | Crossbench who is likely to form government is already ‘legitimate’; question of if they will be tarred is unclear due to this only happening once (at state level, does not seem to tar minor parties) |

Longer-Term Factors are also Driving this Shift

Consider some of the defining social changes of our time: increasingly, people have been driven into smaller social communities by social media, Covid, and a withdrawal from participating in political parties or community organizations; this has enabled fringe perspectives to more easily take hold in the electorate.[viii] This builds on further frustration that has been observed globally related to downward mobility experienced by some groups.[ix]

Voting systems and political economies have also driven this change. The change is (quite obviously) concentrated among political systems with some form of preferential voting or proportional representation. Beyond this, increasingly politically interested donors have swung their weight around. The prospect of well-funded independent campaigns has given ambitious individuals the ability to seek office without needing to navigate party politics.

Gen Z voters have driven much of this change. Younger generations are less satisfied with democracy than older generations.[x] This is also manifesting as changing voter patterns in Australia. In 2021, Australian 18–24-year-olds rated themselves the most centrist since 2006, a sharp repudiation of the previous generation’s leftward tilt over the last six years.[xi] Such a shift among youth is particularly concerning as first forms of political engagement tend to be closely correlated with lifetime behaviors.[xii]

Australia Typifies These Global Trends

Australia’s compulsory and preferential voting leads to the convergence of parties to the center. Historically, major parties have contested this center, and minor parties have campaigned on the edges. But more recently, major parties are becoming more extreme on some topics (for example, climate change) and homogenous on others (such as asylum seekers), driving minor players to increase their contestation of the center.[xiii]

Climate-focused independent candidates (typically professionally successful women in inner-city seats) have typified this shift. These candidates, known as “teals” due to their policy positions being between the blue of the conservative Liberal party and the progressive Greens, currently hold seven of 151 lower house seats. They have been enabled by the Liberal party’s rightward shift on issues like climate and by the presence of heavy financial backing to supplement grassroots campaigning. In 2022, two teals spent over $2m, an extraordinarily high amount for a seat.[xiv]

But fringe parties are also looming on the horizon, potentially reinforcing centrist minor parties’ power. In late February, Clive Palmer (a multi-billionaire mining tycoon) launched his explicitly Trump-inspired Trumpet of Patriots party. The major parties have all condemned Palmer’s previously elected parliamentarians.[xv] Palmer has previously spent more personally than the Labor party in the 2022 election. This war-chest creation and ongoing campaigning shows their strength against the major parties in the seats they are contesting. If the Trumpet of Patriots takes seats away from the Coalition’s right-flank, it would increase the teal’s leverage over the chance of the Coalition forming government.

Major Parties Face a Choice in Dealing with the Prospect of Minority Government

In the upcoming Australian election, major parties have three possible approaches for engaging with the crossbench. Each approach varies in the extent of collaboration with minor players, and are influenced by concerns major parties have about eroding their own legitimacy and share of vote. The Australian context provides useful lessons for other countries, with the centrist nature of these players providing a variation from typical coalitions with fringe parties.

One approach is for leaders to commit to not forming a partnership with minor players while campaigning, despite being willing to do so if needed. Australia’s politicians have chosen this before: in 2010, then-PM Julia Gillard and opposition leader Tony Abbott each attempted to form government with the crossbench, despite both ruling this out during their campaigns. But this requires caution: Gillard formed government and passed substantial reforms such as the NDIS (Australia’s disability insurance scheme), but compromising on election commitments (like establishing a carbon tax per crossbench demands) led to substantial backlash.

In the UK, David Cameron and Gordon Brown also took this approach in 2010. Despite his commitment, Cameron formed a coalition with Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats (Lib Dems). While this coalition drove major changes (e.g., austerity, education funding reform), this led to backlash from voters, especially against the Lib Dems, who saw their popular vote tumble from 23% in 2010 to less than 8% in 2015. While there are multiple drivers for this, forming a coalition was a contributor. Some Lib Dem voters viewed deciding to join a coalition as the most unpopular element; others, like students, objected to the elements of the reform agenda (e.g. tuition reform) that the Lib Dems supported.[xvi]

An alternative approach is to “hold the line” and call another election in the instance that there is no clear winner. Political lore in Australia has deemed this unwise; with mandatory voting, the electorate has typically looked unfavorably of being forced to go to the polls. Australian governments seem haunted by the political wipe-out that the Whitlam Government faced after 1975’s early, infamous return to the polls after the governor-general removed the sitting prime minister for being unable to pass his budget. For some, the memory of this 30-seat loss and 7% swing faced by Labor – who just one year earlier had comfortably won government – is enough to be wary of early returns to the polls.

Israel has taken this approach more recently. With four elections between 2019 and 2021, the country faced instability and popular backlash over the span of two years, with the Knesset bringing on several elections after no party could form government. While Netanyahu’s hard-ball strategy stalled at one point (with an anti-Netanyahu group forming government in 2021), the former prime minister eventually returned to government in 2022.

A final approach – and one which has been reluctantly adopted by Opposition Leader Peter Dutton – is to publicly sound-out or commit to seeking deals with minor players.[xvii] This approach is risky but may pay dividends. On the upside, forcing centrist independents to pick a side could either guarantee Dutton a clearer pathway to government (if they side with him), or allow him to paint a vote for independents as a vote for the unpopular incumbent government (if they side with Labor). On the downside, should independents suggest they won’t form government with Dutton, this will challenge his ability to govern and possibly expose him to attacks from teal-funded resources.

This approach has limited historical precedent. For those watching, the impacts of such a forward confrontation of the prospect of minor parties will be instructive.

So What?

How Prime Minister Albanese and Opposition Leader Dutton navigate this bind could define Australian politics for years to come. For interested observers of global politics, the upcoming Australia election is another data point for how to manage the increasingly common minority government phenomenon driven by the decline of major parties.

[i] YouGov, “2025 Australian Election: MRP polling,” YouGov, 29 March 2025, https://perma.cc/LZ7L-BH7E, https://au.yougov.com/elections/au/2025.

[ii] A longstanding, formal alliance of the conservative Liberal and regional National parties

[iii] Amy Nethery, “‘If Not Now, When? If Not Us, Who?’ The Teals’ No-Nonsense Blow to the Two-Party System,” Social Alternatives 41, no. 4 (2022): 12–18.

[iv] Jill Sheppard, “2022 Australian Federal Election,” Research Paper, 2024-25 (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, December 20, 2024), https://perma.cc/HRE9-PSRT, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/Research/ Research_Papers/2024-25/2022_Australian_Federal_Election.

[v] Author analysis of GoG data, using type of government variable (cpds_tg) and counting the total number of minority governments in each year, once filtering for OECD membership: Teorell, Jan, Aksel Sundström, Holmberg Sören, Rothstein Bo, Natalia Alvarado Pachon, Dalli Cem Mert, Rafael Lopez Valverde, Victor Saidi Phiri, and Laura Gerber. 2025. The Quality of Government Standard Dataset, Version Jan25. University of Gothenburg. The Quality of Government Institute. https://doi.org/10.18157/QoGStdJan25.

[vi] The Brussels Times, “‘Arizona’ Coalition Emerges as Belgium’s Latest Hope for New Government,” The Brussels Times, July 7, 2020, https://perma.cc/H8VA-2M9Q, https://www.brusselstimes.com/120445/arizona-coalition-emerges-as-belgiums-latest-hope-for-new-government.

[vii] Crossbench members can formally become part of the Government (holding ministries and policy responsibilities) or stay outside of Government (guaranteeing passage of budget bills and negotiating all other legislation). The Gillard minority Government saw the crossbench not join government.

[viii] Ngaire Woods, “Why Young Europeans Are Embracing the Far Right,” Oxford Blavatnik School of Government Voices (blog), June 28, 2024, https://perma.cc/CMJ3-TN85, http://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/blog/why-young-europeans-are-embracing-far-right.

[ix] Thomas Kurer and Briitta Van Staalduinen, “Disappointed Expectations: Downward Mobility and Electoral Change,” American Political Science Review 116, no. 4 (November 2022): 1340–56, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000077.

[x] Christopher Giuliano, “Voting Patterns by Generation at Federal Elections since 2001,” Flagpost (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, March 28, 2023), https://perma.cc/W9JT-CQSF, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/Research/ FlagPost/2023/March/Voting_patterns_by_generation.

[xi] Ian McAllister et al., “Australian Election Study 2022,” December 2022, fig. The Left-Right Dimension, https://australianelectionstudy.org/interactive-charts/.

[xii] Marc Merdeith, “Persistence in Political Participation”, Quarterly Journal of Political Science 4, no. 4 (October 2009): 187-209, https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00009015.

[xiii] Australia is somewhat uncommon in the sense that its minor players have contested the center, while globally minor parties typically have occupied the fringes. One major exception to this is the United Kingdom’s Liberal Democrat party, which has occupied the center as a minor party; however, the LibDems have suffered reduced influence over the past 10 years.

[xiv] Kate Griffiths and Jessica Geraghty, “New Political Donations Data Show Who’s Funding Whom,” Grattan Institute, February 3, 2025, https://perma.cc/5YKS-F29F, https://grattan.edu.au/news/new-political-donations-data-show-whos-funding-whom/.

[xv] Jake Evans, “Senate Censures Lidia Thorpe over King Charles Protest and Ralph Babet over Offensive Tweets after Trump Win,” ABC News, November 18, 2024, https://perma.cc/ZXB9-B5CF, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-11-18/lidia-thorpe-and-ralph-babet-censured-by-parliament/104613292.

[xvi] John Harris, “The Strange Death of the Liberal Democrats,” The Guardian, July 12, 2015, https://perma.cc/EQ5W-DKJK, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/jul/12/strange-death-of-liberal-democrats-leadership-vote.

[xvii] Sarah Basford Canales, “Dutton Names Crossbenchers Who Could Help Him Clinch Minority Government as Poll Puts Coalition Ahead of Labor,” The Guardian, February 16, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/feb/16/dutton-ponders-minority-government-deal-with-crossbenchers-as-coalition-outstrips-labor-in-latest-poll.