BY SAMUEL STOLPER

Like it or not, renewable portfolio standards (RPSs) are a major part of United States climate and energy policy. Thirty states and the District of Columbia have enacted RPSs, and seven more states have analogous voluntary (non-binding) programs[i]. RPSs have been active since the early 2000s, so some states have as much as a decade’s worth of experience with them. And yet next-to-nothing is known about their compliance costs, their contribution to climate mitigation, or their impact on consumers’ wallets.

What is an RPS? At the most basic level, it is a requirement that electric service providers (read: utilities) purchase a certain percentage of their electricity from renewable energy sources (e.g., wind, solar, landfill gas). That percentage usually rises over time. For instance, the Massachusetts RPS level began at one percent in 2003 but is currently at 8 percent and is slated to reach 15 percent by 2020[ii]. Renewable power generation is almost always monitored and verified through a crediting system: each unit of power produced nets its generator one renewable energy credit (REC). Every electric utility that serves customers in a given state must, in turn, secure enough RECs by the end of each year to meet that state’s RPS. More often than not, there is a set, per-unit Alternative Compliance Payment (ACP) that can be made in place of securing RECs and which acts as a sort of ceiling on compliance costs.

Although this broad structure is common across the country, there is otherwise a striking lack of uniformity among state RPSs. The percentage requirement and its rate of increase over time both vary by state. There are exemptions galore. Each state defines “renewable energy” differently, and some states give particular renewable sources priority over others. The extent of regional, out-of-state eligibility of renewable sources varies widely. Furthermore, the policies operate within complex and inter-related electricity markets. All this makes it difficult to identify the true impact of RPSs, let alone that of any single RPS design element.

Good policy analysis, however, starts with the right questions. Unfortunately, researchers are not even doing that. The small but growing academic literature[iii],[iv],[v],[vi] on RPS impacts almost exclusively starts with the following research question: What have been the effects of RPSs on in-state renewable energy capacity and generation? Predictably (given the complexity of the policy context), the answers to this question have been very inconsistent.

However, the larger problem is that the question itself is misguided.

RPSs are developed by individual states, one at a time, but markets for power generation are generally regional. Eligibility of renewable power generators for a given state’s RPS is also typically regional. Policy analysis of RPSs must therefore have a perspective that is regional. Studies that ignore what is happening in neighboring states, such as those cited above, provide an incomplete picture of RPS performance.

Anecdotal evidence illustrates this point clearly. Consider New England: six states, five different RPSs (Vermont has only a voluntary program), one power market. A single, independent system operator ensures that electricity demand is balanced with electricity supply across all of New England, so that rising demand in Massachusetts (for example) can be met by an increase in electricity generation in Maine. Moreover, all five states with RPSs allow their utilities to secure renewable energy credits from anywhere in New England (and even from neighboring power markets, such as New York and Quebec). What does this mean? It means that Massachusetts utilities companies can purchase renewable electricity from other states, if it is more economical for them to do so.

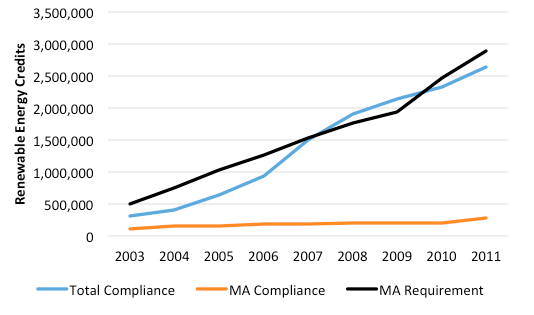

Figure 1. Annual Compliance with Massachusetts’ RPS

[Data source: Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources]

Figure 1 portrays the official Massachusetts RPS requirement and actual compliance by the state’s utilities. The RPS requirement for RECs[1] (black line) rises over time, as stipulated by state regulators. The number of RECs used in compliance that originated at power plants within the state of Massachusetts (orange line) rises only negligibly; it does not follow the overall requirement at all. However, the total number of RECs used in compliance from any eligible state (blue line) follows the overall requirement quite closely.[2] So the RPS is largely being met, but not by Massachusetts renewables. The majority of Massachusetts RPS compliance actually comes from power generation in New York and Maine[vii], with smaller portions coming from the rest of New England and its surroundings.

The story told by Figure 1 is unlikely to be unique in the U.S., because most state RPSs allow some manner of out-of-state eligibility or inter-state REC trading. Asking whether in-state renewables grow in response to rising RPSs misses this point. It misleadingly frames a lack of in-state renewables deployment as a policy failure. In fact, it may be just the opposite. Some states are simply better suited than others to generate renewable power. Allowing utilities to contract with generators in such states likely reduces costs while sacrificing little in the way of climate impacts and energy security.

The upshot? We, the researchers and policy analysts, should not be asking merely whether RPSs have affected in-state outcomes. We should be asking whether RPSs have affected regional outcomes, since regions are the true locus of policy incidence. Before we can provide answers, we need to pose the right questions.

NOTES:

[1] RPS level is officially defined as a percentage of total electricity supply in a given year. It is, however, graphically more convenient to represent the RPS level by the actual, absolute REC requirement, as is done on the y-axis.

[2] The discrepancies between the black line (RPS requirement) and blue line (actual RPS compliance) can be explained by alternative compliance payments (ACPs) as well as banking of RECs for use in future years.

SOURCES:

[i] State Reports, Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency. Accessed October 2013. <http://www.dsireusa.org>

[ii] Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (2013). “Massachusetts RPS & APS Annual Compliance Report for 2011”, p. 5. <http://www.mass.gov/eea/docs/doer/rps-aps/rps-aps-2011-annual-compliance-report.pdf>

[iii] Yin, H. and N. Powers (2010). “Do State Renewable Portfolio Standards Promote In-State Renewable Generation?” Energy Policy 38: 1140-1149.

[iv] Delmas, M.A. and M.J. Montes-Sancho (2011). “U.S. State Policies for Renewable Energy: Context and Effectiveness.” Energy Policy 39: 2273-2288.

[v] Prasad, M. and S. Munch (2012). “State-level renewable electricity policies and reductions in carbon emissions.” Energy Policy 45: 237-242.

[vi] Shrimali, G., S. Jenner, F. Groba, G. Chan, and J. Indvik (2013). “Have State Renewable Portfolio Standards Really Worked? Synthesizing Past Policy Assessments to Build an Integrated Econometric Analysis of RPS Effectiveness in the U.S.” Electricity Journal (forthcoming).