By Shloka Nath, News Editor, MPP ‘13

In May this year, Malcom Gladwell wrote a piece for the New Yorker on what it means to innovate. He painted the picture of a 24-year-old entrepreneur named Steve Jobs who, in 1979, visited the legendary headquarters of Xerox in Silicon Valley, staffed at the time with the world’s most brilliant computer scientists. It was where Steve Jobs would first see a vision of the mouse. Struck by his “Eureka” moment and rapidly dreaming up the future of the human-to-computer interface, Jobs sped back to his little start-up called Apple and the rest, as they say, is history.

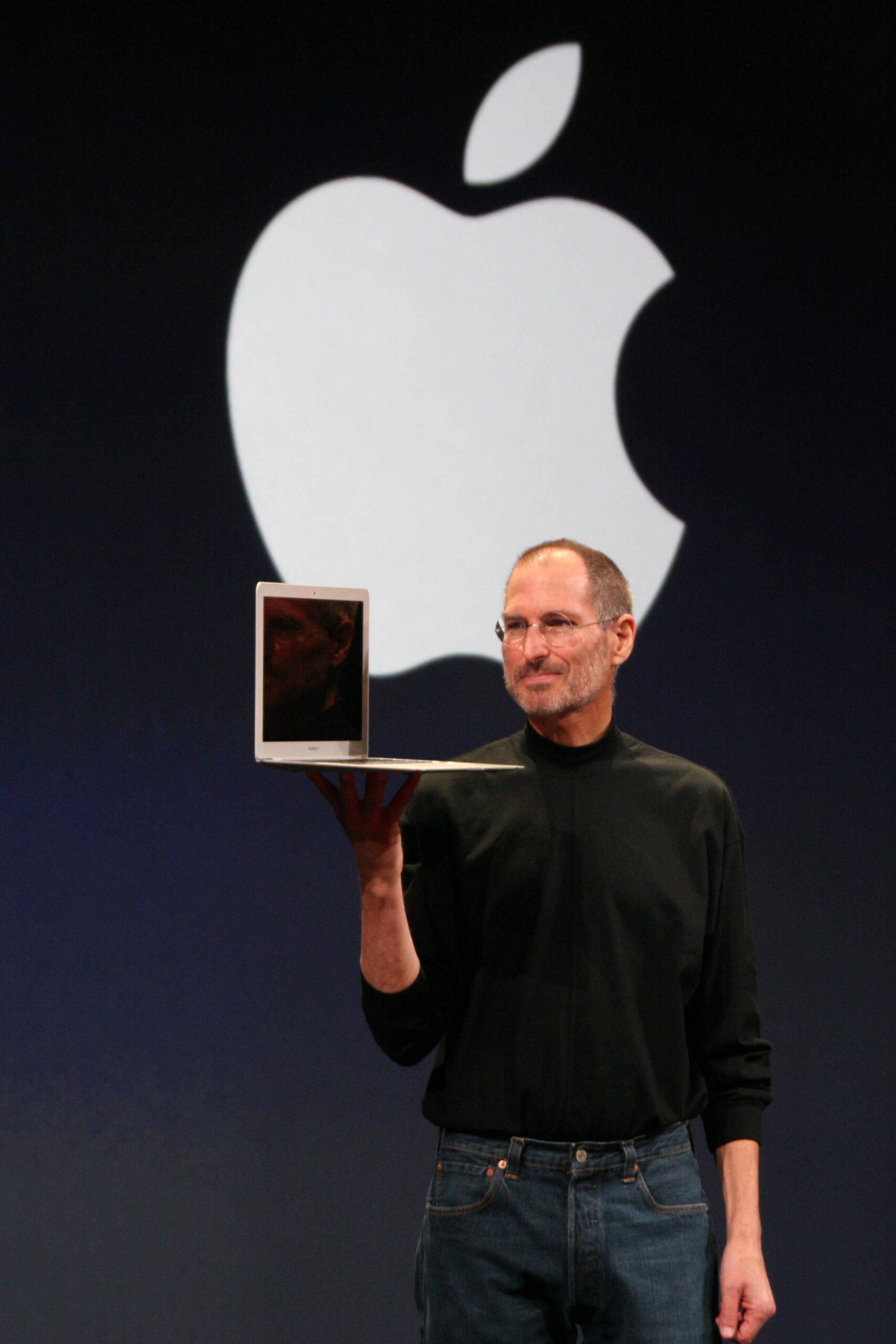

Malcolm Gladwell’s assessment of those events so long ago creates an important distinction in our understanding of Steve Jobs, the pioneering technology guru who contributed so much to the evolution of consumer technology. Jobs’ real genius was to perceive this truth: the role of the innovator is not necessarily to find completely new ideas, but to apply fresh approaches to old ideas and make them new again. And so it goes for Apple; few public companies have been as intertwined with their CEOs as Apple was with Jobs, who co-founded the computer manufacturer in his parents’ Silicon Valley garage in 1976, and over 20 years later — in a comeback as magnificent as it seemed implausible — yanked it from near-bankruptcy and turned it into the most valuable technology company in the world.

Jobs died on October 5th of respiratory arrest caused by a pancreatic tumour, according to the death certificate. He resigned as Apple’s Chief Executive Officer in August after struggling with his illness for more than 6 years; he was diagnosed in 2003 and underwent a subsequent liver transplant. He leaves behind the legacy of an enduring message: that technology is a tool to improve the quality of human interaction and to unleash creativity. From the Macintosh, to the iPad, iPhone and iPod, Jobs has advanced one industry after another, from music to computers, to smartphones and even movies.

Life however, did not start out in quite such a ruddy manner. In fact, Jobs’ career traces a mythic sweep that few entrepreneurs in America can attest to. He was adopted by a Californian middle-class family and subsequently dropped out of college only to become one of the central figures in what was termed the “computer revolution” before the age of 30. Shortly thereafter he was forcibly removed from the company he created, and spent the next portion of his life in industry exile, struggling to restore his reputation as his fortune dwindled. Still, Jobs’ banishment served him well; a number of innovations were born during this period and he developed a marked talent for showmanship evident in later years when he turned the release of every new gadget into a cultural event.

Not everyone was enamored of Jobs. Most critics are quick to point out his disdain for the kind of philanthropy that has burnished the reputations of his wealthy peers, like Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates. He had no record of charitable giving, believing that his company was enough of a legacy. His employees have described him as a “tyrant” in his fanatical and demanding need for perfection, and his industry peers frowned upon his public derision of competitors as “bozos.”

In 2005, in a Stanford commencement speech, Jobs touched on mortality and its significance as a shield against complacency.

“Death is very likely the best invention of life,” he said in the speech. “All pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure, these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important.”

Jobs is survived by his wife of 20 years and his four children.