The Islamic State has been quick to trumpet the diversity of recruits its siren call has attracted. This picture is from issue 12 of their English-language magazine ‘Dabiq’.

With the rise of the Islamic State, for the first time in nearly 100 years the call to prayer was heard in a caliphate. But the muezzin call of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was not merely incanted from a minaret in Mosul – in the ancient style his followers claim to espouse. Nor was it just broadcast across the rooftops of Raqqa. His siren song has been digital; tweeted and posted, blogged and hashtagged, it has drawn young Muslims from across the globe into his arms.

Drawn in by the same slick advertising and online media used by everyone from political campaigns to drug companies, it has been western millennials, who grew up with the same TV shows and popstars, smartphones and designer brands as so many of us, that have been the heart of IS’ recruitment strategy.

So it should be of little surprise that the Islamic State has its own emojis.

The group, whose startling online presence as much as their unfettered brutality has distinguished them from other jihadi organizations, has turned to the yellow smiling faces as the latest installment in their internet infrastructure.

A far cry from the comical cartoon figures that now inhabit our text and whatsapp messages, Islamic State sympathisers have released a range of digital icons inspired by the group’s murderous legacy, with stickers celebrating the execution of jumpsuit-clad prisoners among the selection and others showing Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Islamic State’s ideological founder. The digital icons often depict some of the group’s most gruesome murders accompanied by small smiling emojis.

Disseminated on the cloud-based encrypted app Telegram, the 96 pictures were easily downloadable by IS supporters as, Telegram long had a reputation for being reluctant to censor controversial accounts. (After being revealed by journalists, Telegram announced, in an unprecedented move, that it had deleted some 78 IS-affiliated accounts in 12 languages – a sign of the scale of the problem).

Epitomising IS’ self-celebrated brutality, these macabre downloads are a more flippant accompaniment to the official IS magazines and videos, fan-made songs and amateur footage from the conflict in Syria and Iraq. Nevertheless, they are a powerful tool in IS’ online arsenal of information. Following the November 2015 Paris attacks IS supporters released a series of memes glorifying the murder of dozens of Parisians.

This millenial strategy is no longer limited to one militant group. No doubt inspired by Islamic State’s internet presence, other militants, including supporters of Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthis, are sharing their own digital stickers. Some show Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, accompanied by his quotes, while others picture a burning star of David. Telegram has also used by Palestinian groups to crowdfund weapons.

A History Of Online Hate

Al-Qaeda were the first to innovate with the Internet to advance their global jihad, releasing audio and video files of rallying cries and attacks across the world. But it is IS that has become the true masters of the Internet insurgency, displaying a fluency with western life far removed from the caves of Afghanistan.

Cyberwarfare is not absent from the conflict against IS, as the group has reportedly carried out cyber attacks before. But their greatest weapon lies not in hackers but in likes, retweets and the simple hashtag.

IS have used the internet to mould a community of online followers, inspired by the group’s incredible battlefield victories, territorial conquest and prophetical discourse. Through this network of loyal recruits, followers and sympathisers across the Internet – in many ways the group’s lifeblood – IS has been able to popularise a vision of ‘just terror’ and draw in yet further resources and recruits.

IS’ tens of thousands of supporters online, willing to retweet and post online ,are most definitely part of the wider IS community even if they haven’t followed the call of their so-called Caliph and migrated to his ‘land of the believers’. Although inconceivable that social media isn’t a part of IS’ overall strategy, the legions of IS fanboys can’t be considered an official arm of the organisation. Some accounts have been run by officially-backed publicists and others, managed by westerners who have migrated to IS, hold a pseudo-official standing in the online community, gaining influence and followers from the pictures and posts of daily life in the ‘Caliphate’.

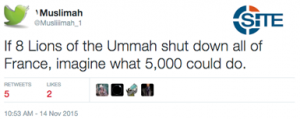

A message tweeted by an IS supporter in the aftermath of the November 2015 Paris attacks referencing the 8 attackers.

An entity that prides itself on, and is never far from boasting of, its establishment of a territorial state, replete with bureaucratic, welfare and educational programmes, the Islamic State also relies on this community of online citizens. Make no doubt about it, online resources from IS ‘fanboys’ (and girls) are a pillar of the virtual and global community that is so important to the Islamic State’s successes and future vision.

IS has displayed an impressive and unnerving talent at waging a global hearts and minds campaign in the 21st century. Both building and utilizing a multimedia machine that would put most broadcasters to shame, it has constructed a narrative and imagination of the Islamic State so compelling that it has appealed to young Muslims from the most unlikely of jihadi backgrounds. The three 15-year old British schoolgirls who ran away to Syria after booking cheap flights to Istanbul are perfect examples of this; the Internet age has made even Western children vulnerable to radicalization.

Central to this recruitment has been its supporters’ use of mainstream outlets like Twitter and Ask.fm as well as more specialised apps and software. While Ask.fm, the online question forum, gained a reputation as a staging post and information trove for would-be jihadis, Twitter has become arguably the most influential IS mouthpiece. With thousands of accounts professing support for IS across the world, predominantly in Arabic but with a large following tweeting in English and a host of other languages, IS’ message has become hard to ignore. The majority of these ‘IS fanboys’ are anonymous – typically daubed in jihadi art and nicknames – and provide an echo chamber for the IS party line, retweeting propaganda material, trolling analysts, journalists and anti-IS voices, and airing messages of support.

In mid-2015, an British jihadi, Neil Prakash, who used the nom de guerre Qa’qa Al-Britani, tweeted messages to his supporters trying to crowdsource the address of a Sydney-based journalist that had exposed his real identity. Although easy enough to write off as a baseless threat – a symptom of an age in which many abuse the giddy anonymity of the internet – the journalist took it very seriously. Some six months prior to the tweet Australian counter-terrorism police had warned him of a plot masterminded by Prakash to kill him and his co-writer.

But as loud as the group’s online voice might be, it would be wrong to conflate the resonations of IS’ message in Internet’s echo chamber with mass appeal. The Internet is so central to IS’ strategy because its message is able to reach such a small, disparate minority of fertile recruits. Amongst them, a vocal few on social media are able to amplify their vitriol exponentially. Even so, these accounts aren’t the staple of most Twitter users’ newsfeeds and do inhabit a particular sphere of the twittersphere – one that these IS netizens have tried to break out from. In the run up to the 2014 Rio World Cup, the official #WorldCup2014 hashtag was hijacked by IS supporters as their troops marched across Iraq. Maximum publicity for their rampage of blood and chaos was guaranteed, especially in the most unlikely of quarters – the online sporting world.

The IS community has made full use of anonymous profiles on file-sharing apps like Telegram or YouTube to share information and material with their followers. The gross inability of such websites to monitor content has been unveiled repeatedly as gruesome videos glorifying the murder of IS victims have gone viral. Recent efforts to counter trolling in particular have given greater power to those reporting unsavoury accounts and have resulted in some minor successes but migrating anonymous accounts has become all too easy. With personas that on average had 1,000 followers, typically double up accounts or post alternative handles for fans to follow, allowing them to skip around restrictions with ease. Although now social media companies are making their sites increasingly hostile environments for ISIS propagandists, in February Twitter said that since summer 2015 the site had shut down 125,000 ISIS accounts.

In addition to leeching off the arteries of the social media world, IS netizens have created their own channels, showing off their familiarity communicating within the millennial generation. Dawn of Glad Tidings was an IS supporters’ app that allowed subscribers to offer up their social media accounts as bots through which IS spokespeople could spread their messages. When ISIS took Mosul, the app allowed the 40,000 tweets to be posted by the group in a single day. Sporting a finesse common to their video footage and online publications, the app points to the group’s comfort within the trappings of 21st century society. Despite the paradox of employing smartphones and social media accounts to further a vision of society entrenched in the spartan realities of 7th century Arabian life, IS are unrepentant of their mastery over insurgent social media. Not only as a tool of great utility within its own community, IS has relied on its multimedia productions to speak to the world, boasting of its activities, goading its enemies and, it hopes, instilling fear wherever they are watched.

Following the November 2015 attacks in Paris, IS supporters released a series of memes glorifying the murder of Parisians.

No Broken Promise

IS’ online mouthpieces provide a unique propaganda value when attacks are occurring in its caliphate’s name across the globe by a variety of disparate actors and even individuals. Islamic State have a strong track record of promising attacks or victories and then following through with them, although the past year has seen them resort to more blatant propaganda regarding their losses. In a video captured by ISIS showing Americans training Syrian opposition troops, the US advisors admit as much themselves.

Moreover, when attacks occur in their name but seemingly without their support, they are still able to claim them as their own. Unlike the Paris attacks, after which IS’ English-language magazine ran a profile of one of the bombers, terrorist incidents like the killing of a priest in Rouen or the Nice truck attack appear to have occurred completely without the group’s prior knowledge. Even so, IS was able to claim them as their own, which holds particular value – especially given that the Nice attack was the group’s deadliest within Europe.

Many commentators in the media have called for a blanket ban on IS coverage – a prospect that sits uncomfortably with some journalists – while other organisations like the BBC have decided not to publish footage produced by IS.

Central to much of IS’ rhetoric is the ‘coming about’ of the Quran’s apocalyptic prophecies, ending in a final showdown with the ‘armies of Rome’ in the Syrian town of Dabiq. IS’ atrocity videos have a secondary role in goading their enemies into aggression, in IS’ eyes hopefully bringing about the final clashes of the apocalypse. American and Jordanian bombs in the aftermath of the execution of Jim Foley and Muath Al-Kasasbeh were greeted with glee within IS’ twitter ranks for just this reason.

As a patchwork of armed forces, from the Iran and Russia-backed Assad regime to the Kurds, the Gulf-backed Islamist groups to the recent Turkey-backed incursion into Northern Syria march towards Raqqa and Mosul, the Islamic State group is on the defensive. If nothing else, its own future seems to hold an inevitable air of the apocalypse about it. However thoughts that the group will disappear once its territorial control is vanquished seem naive. Based on past precedent and the considerable support that Islamic State was able to win from disenchanted Sunni locals in Iraq, a future insurgency by the group appears likely. It is almost impossible to say how this will affect the waves of IS-backed and IS-inspired terror attacks in Europe. What is certain though, is that the archives of IS material across the web – its virtual legacy – will play a key role in the future threat the group poses, even if it no longer exists.

For all its harking back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad, the Islamic State is a thoroughly modern caliphate. Dreamt up by IS’ leaders as an ultra conservative doctrine, in practice the workings of the Islamic State have embraced the 21st century wholeheartedly. The Internet has been key to realizing the international community of followers united around IS’ exclusive interpretation of the Quran. Spurned and rejected by the vast majority of Islam, only through downloads, video chats and instants messages has the so-called Islamic State managed to unite, both physically and ideologically, its recruits. The paltry efforts of the international community to combat this unique threat of the Millennial Caliphate is yet another indicator of how far we are from finding a strategy to defeating IS.

Islamic State has been in the international eye for over 2 years – although the group has existed since 2006 – and yet still, despite the coalition of the world’s most powerful militaries that stands against it, the group persists. Online, Islamic State is still able to spread its message, forging a legacy as the first milennial caliphate and no doubt inspiring future generations. While social media platforms have finally begun to respond in force to militants’ use of their technology, it may be too late. Governments, companies, and all those civil entities combatting radicalisation in our societies, and violent extremism in our world, were slow to realise how the young, vulnerable, or disillusioned in our societies were being led astray. IS’ message and discourse has been spread far and wide; Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi’s legacy won’t be carved in stone, but etched into the corners of the internet, never lost, never forgotten.

Earlier this summer I spoke to the head of one of the UK’s grassroots anti-radicalisation efforts. He bemoaned the shock of anti-terror officers when he told them that children were showing him IS propaganda videos on snapchat – the latest offering of the social media world. They had no idea it was happening, and little thought of how to react.

We may have invented the light switch, but we are still in the dark.