The lights shine, the cameras zoom, and the serious intro music fades. “Let’s talk about the hottest topic: the economy,” says the CNN Türk news program host. On the left are three journalists from mainstream Turkish news outlets, on the right is Muharrem İnce, the presidential candidate of CHP, the center-left party and opposition candidate with the best shot at unseating president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

The stone-faced journalist from Hürriyet asks the first question: “It is said that speculators, FETÖ (the term for the followers of accused coup plotter Fethullah Gülen), and economic masterminds are working together and have hurt the capacity of the AKP to help the economy. It’s an economic coup, they say. What do you say?”

İnce doesn’t take the conspiracy theory bait. “I’m a physics teacher. There is a logic in physics. There is a logic in economics,” he replies. “There is a foreign beneficiary of this debt of Turkey’s. Does this foreign creditor want default? How’s the creditor going to get repaid?” Not scapegoating foreign speculators, he goes on to note that most of the foreign debt was accumulated while the AKP was in power.

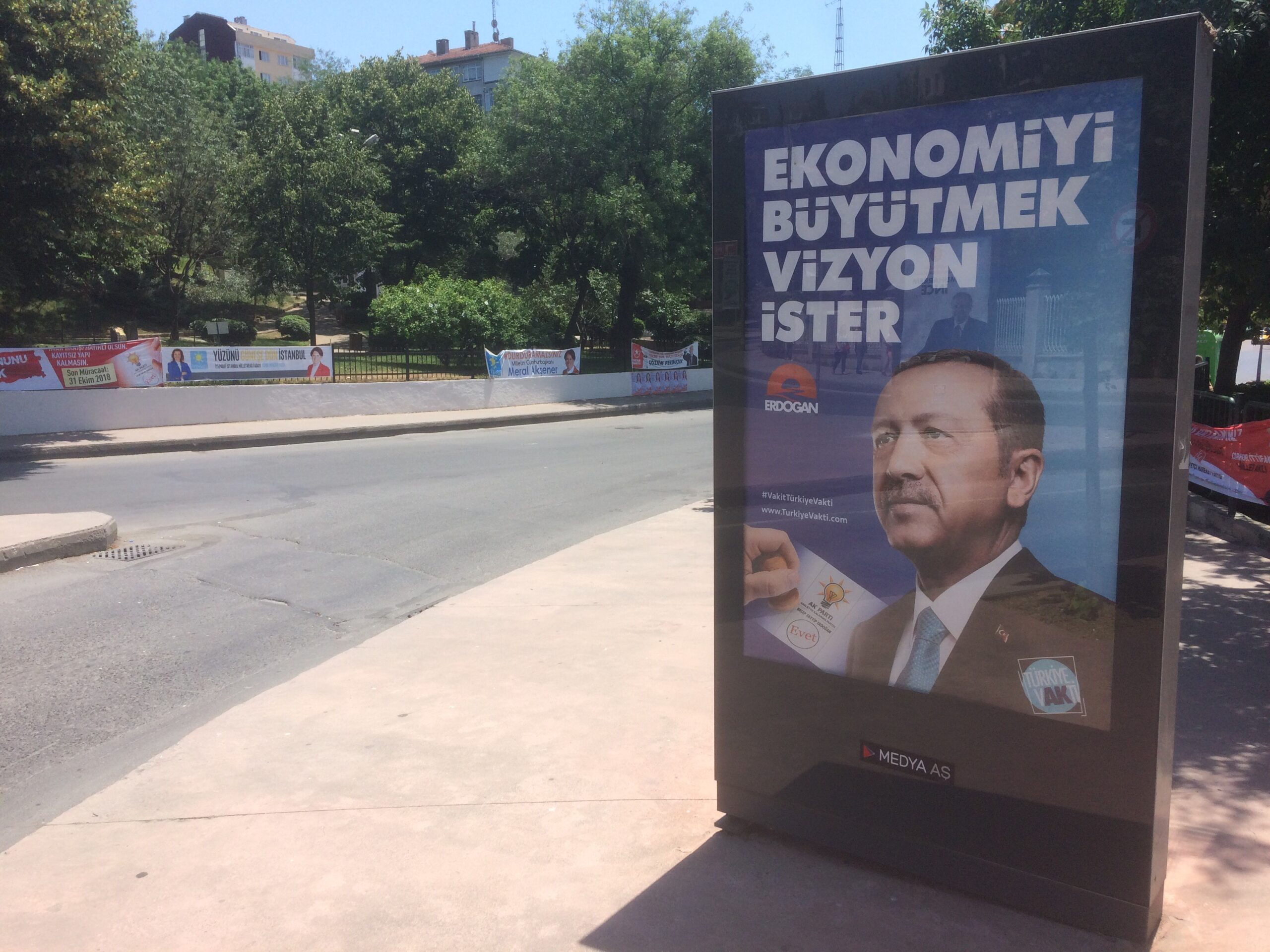

That stance is in stark contrast to Erdoğan’s recent bombastic statements blaming outsiders: “Don’t pay attention to the games played through exchange rates!” the president told a rally of supporters in Sakarya, referencing the decline of the Turkish lira against major currencies. “After June 24, we will settle accounts with those who make such manipulations. We will issue a serious manifesto for them.”

A casual observer of Turkish politics would be forgiven for thinking that regional geopolitics, social issues, the Kurdish issue or the hosted refugees are the central points of the election. Not so. Somewhere in Turkey, a political strategist is hammering home to her client: “it’s the economy, saftirik (stupid).”

Pocketbooks will tip the scales as Turks head to the polls on June 24 to select, for the first time, parliamentarians and a president simultaneously in the new executive-style polity.

As long as the economy was chugging along and ordinary citizens saw the opportunity to join the growing middle-class, Turkish voters were willing to put up with a lot intolerant and divisive leadership. “When he set up his AKP in 2001, Erdoğan’s strength was rooted in his ability to dream prosperity and more freedoms for Turkish citizens,” said Soner Çağaptay, author of the recent book The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey. “When Erdoğan came to power in 2002, Turkey was a country of mostly poor people; it is now a country of mostly middle-income citizens.”

Now the economy is faltering — somewhat. Turkey’s foreign accounts deficit has exceeded $400 billion, the lira has lost more than 20 percent of its value versus major currencies this year, and perhaps most tellingly, Turkey leads the world in number of millionaires fleeing the country and taking their assets with them. Although exports to the Eurozone have steadily gone up and tourism has finally expanded for the first time since 2015, inflation has reached double-digit levels and the current accounts deficit has risen above 5 percent, at the same time, that the country is facing pressures from higher oil prices.

Despite these recent economic woes, Erdoğan is still loved by huge numbers of Turks. According to Çağaptay: “Half of the country hates him, but the other half adores him and thinks he can do nothing wrong. The latter part will therefore agree with him, if an economic meltdown happens, that this is driven by outsiders and the domestic opponents who want to undermine Erdoğan.” While his supporters see outsider machinations, his opponents suspect that Erdoğan called for early elections because he saw that the economy was in for a rough ride, and later elections would have meant that voters’ wallets might have been affected enough to erode his support even more.

However, there seems to be little optimism that the opposition can steer Turkey’s economy away from decline. “No one has an economic program for Turkey. (The opposition) have no plan, neither does Mr. Erdoğan,” said a Turkish real estate expert, who asked to remain anonymous. According to him, the weak lira might prevent the next Turkish government from getting the financing it needs for major infrastructure projects, which have been key for keeping the economy moving in the recent past.

Whoever wins the elections on June 24 and whatever political wrangling takes place, Turkey’s government will have to navigate rough economic waters. In the long term, Turkey needs to invest in developing a more nimble, flexible and better educated workforce that is able to pull its weight in the global knowledge economy