International media and human rights groups place much focus on Israel’s ongoing occupation of the West Bank and its accompanied detrimental effects. However, outside the confines of this well-reported conflict is the lesser-known and lesser-regarded condition of Israel’s own Arab population. While Israeli Arabs are offered equal citizenship, freedoms, and voting rights as Israeli Jewish citizens, there have been disturbing trends regarding this large minority, which accounts for 20.7 percent of the total population.

In two separate trips to Israel (March 2015 and June 2016), I drove through much of the country’s center and north. The beauty of cities such as Haifa, Netanya and Tel Aviv, with their expansive high rises and impressive infrastructure, is noticeable in an increasingly modern country. Yet what I noticed more often in the midst of Israel’s remarkable modernization were stark differences posed by cities such as Qalansuwa and Nazareth, and smaller localities within the Hadera sub-district. Unlike other Israeli cities, these were marked by poorly paved or dirt roads, and crumbling homes that saw none of the handprints of the aforementioned modernity growing throughout Israel. What mostly stood out, though, was that these localities were entirely or predominately Arab. Visual identification of differences in these Israeli landscapes provides only a segment of the greater story Israel’s Jewish-Arab divide.

Background

Israel’s relationship with its Arab citizens, those who did not flee during or after Israel’s War of Independence, has and still remains difficult. In fact, the term Israeli Arab may or may not be the preferred nomenclature depending on whom you ask when discussing this demographic group. While it remains a credit to Israel as a democratic society that it affords full voting rights to all of its Arab citizens, recognizes Arabic as an official language, and currently contains ten Arab members of the Knesset, the history of Israel and its Arab citizens is more nuanced. As Arabs were granted citizenship at Israel’s outset, they were not granted equal rights or equal duties; this had to do with the predominantly European Jewish majority regarding the Arabs inside the newly-formed Israel as a security risk. As Israeli historian Tom Segev discusses in his 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year that Transformed the Middle-East, security concerns and a desire to stamp out political mobilization resulted in Arabs being subjected to martial law until 1967. Permits had to be obtained from the military in order to travel, for work or otherwise. During that time, Arabs were also paid less than Jewish employees, and did not receive the same benefits as Jewish citizens. It is with this legacy of discrimination, albeit much improved upon from the 1960s, in which inequality between Jews and Arabs continues.

The Data

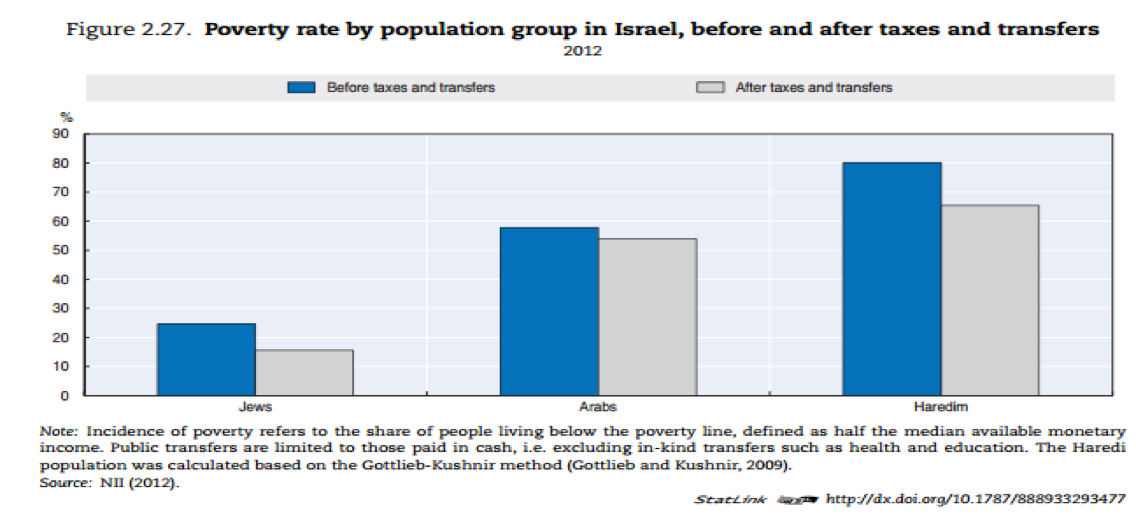

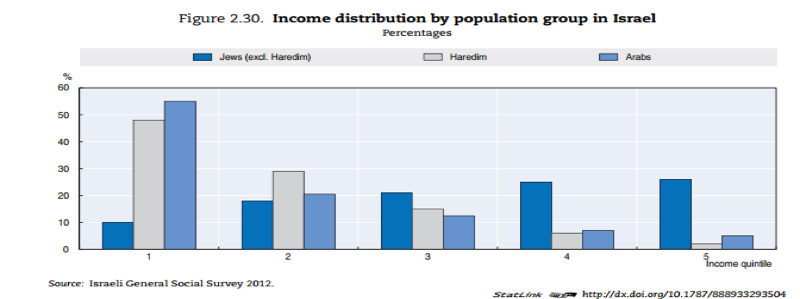

The evidence of Israeli Arab inequality has been identified by way of OECD reports and Israel’s own Central Bureau of Statistics census data. Thanks to Israel’s overall transparency in reporting, its highly detailed ethnic data, and its own self-awareness of this issue, these reports provide accurate and telling data. OECD’s 2015 report, titled Measuring and Assessing Well-Being in Israel, used 11 indicators of the OECD’s ‘well-being framework’ to identify socio-economic outcomes between Jews and Arabs. Perhaps the most noteworthy indicators were poverty rate and income distribution disparities, which show a noticeable distinction between Jews and Arabs.

Most telling here is that 55 percent of Israeli Arabs live in households in the bottom economic quintile, as compared to 10 percent of Israeli Jews (non Haredim).

In addition, Israeli Arab shares of people who are employed, studying towards an academic degree, report that their health is “good”, “very good”, or “excellent”, and say that they are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their lives are lower than those of Israeli Jews. This report shows an explicit disadvantage among Arabs across all available measurable indicators, indicating higher rates of poverty, and lower levels of participation in the labor force, educational achievement, and health status. Furthermore, these indicators will likely continue to be self-reinforcing, as lower levels of education will ensure prolonged economic exclusion from Israel’s labor and job markets.

In an effort to visually display disparities between Israeli Arabs and Jews, I set out to compare the areas where most of Israel’s Arabs reside to these same areas’ level of socio-economic vulnerability.

Israel’s Arabs: Where They Are[1]

1. Using census date from Israel’s Bureau of Central Data and Statistics, I was able to visually display a graphic of Israel’s concentrations of Arab citizens by sub-district. Akko, Yizreel, and Hadera contained the highest numbers of Arabs throughout Israel.

Cartographer: Ryan Gardiner, Tufts University

Date: May 10, 2016

Projection: WGS_1984_UTM_Zone_36

Data Sources: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, Adalah Inequality Report, OECD, Open Street Map, Btselem

Highest Socio-Economic Vulnerability[2][3]

2. I compiled vulnerability indicators in socio-economic categories (i.e unemployment, occupations, education levels, household levels) and developed a scoring system, breaking down percentage data into four thresholds for risk scoring (1 thru 4). I was able to aggregate risk scores across each socio-economic category, eventually compiling these for each sub-district.

3. The next portion of this analysis was locating an element of infrastructure, hospitals, and displaying these points on the map. After finding these from open sourced maps, I ranked them by “distance to…”, making four classes of distance circles around each hospital, 1 signifying areas within 10km (least vulnerable) and 4 signifying areas over 40 km away (most vulnerable). I conducted the same steps for Israel’s roads, 1 signifying areas within 2km (least vulnerable) and 4 signifying areas within 80 km (most vulnerable). These scores were incorporated into the sub-district scores and generated the map seen above.

Cartographer: Ryan Gardiner, Tufts University

Date: May 10, 2016

Projection:WGS_1984_UTM_Zone_36

Data Sources: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, Adalah Inequality Report, OECD, Open Street Map, Btselem

Conclusion

While other factors certainly contribute to socio-economic vulnerability (i.e Haredim and Ethiopian Jewish populations), the fact that the highest Arab-populated sub district (Akko) accounts as the most vulnerable (highest scoring), and that Yizreel, the second highest Arab-populated sub district places in the highest vulnerability threshold, reflects facts on the ground, demonstrating that Israeli Arabs face cross-sector inequalities.

Israeli Efforts to Even the Playing Field

At the end of 2015, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his government approved a five-year plan to invest in and develop the Arab sector, but subsequently attached to it difficult stipulations. The plan had called for $3.8 billion over five years to be invested in housing construction, employment, education, and public transportation throughout the Arab sector. While Social Equality Minister Gila Gamliel and President Reuven Rivlin provided support for the plan, political wrangling ensued and Mr. Netanyahu attached conditions which Arab local leaders were to meet. These entailed combatting illegal weapons in Arab communities, national service requirements, and a requirement for Arab municipalities to transition their building codes as they pertain to multi-story buildings. While not impossible to meet, they are indicative of a national government shifting its responsibilities to an already burdened minority population. It also marked Israeli Knesset opposition to the plan.

But there are signs that this program may yet work. Injaz, the Center for Professional Arab Local Governance, has engaged 35 out of an estimated 75 Arab municipalities thus far in implementing the plan. The municipalities are not waiting for government outreach, but rather spurring growth within their own population centers. While this signifies both Israeli government recognition of the prevailing inequality of the Arab sector and also the growth of Arab municipal resourcefulness, the aforementioned political opposition to this plan highlights the sharp societal divides that remain among politicians and Israeli citizens alike.

Further Thoughts

Traveling through Israel and discussing this topic with Israeli Jews has provided me with both pessimism and optimism for the future of Israel as a multi-ethnic and religious country. On the one hand, Israeli Jews acknowledge the economic disadvantages and poor state of Arab society inside the country as compared to themselves. Many see this as detrimental to the Jewish state’s democratic character and reputation. On the other hand, the desire for hard action to solve this long-standing issue is tempered by a sense of hopelessness in an increasingly hostile political environment that does not bode well for tangible efforts from the government or citizenry. However, continued efforts from the likes of Reuven Rivlin and Gila Gamliel may result in follow-through from the government and sustained pressure to even the socio-economic gap between Jews and Arabs. 40 km away (most vulnerable). I conducted the same steps for Israel’s roads, 1 signifying areas within 2km (least vulnerable) and 4 signifying areas within 80 km (most vulnerable). These scores were incorporated into the sub-district scores and generated the map seen above.