Imagine my shock when, in the course of a lecture at the Harvard Kennedy School, the class was polled about whether satires of the Prophet Muhammad should be allowed and the overwhelming majority favored censorship, self or otherwise. Specifically at issue was the “controversy” that erupted years ago when a Danish newspaper published cartoons depicting images of the religious icon (a big no-no in the Islamic faith) in not-so-ingratiating context.

The former pope seemed to agree with the class. He swiftly condemned the cartoons, and, only as footnote, the looting, pillaging and burning of the Islamic fanatics they had “offended.” Responsibility for this inane misapplication of calumny lies with familiar culprits.

The Offended are ever present and always determined to live up to their namesake. Even in the freedom-loving USA, there is always a risk that a slight linguistic misstep may prompt their committal of forces to a new battle in their ongoing war against the First Amendment to the Constitution and the principles of free expression and inquiry it embodies.

Even their harshest critics must credit the creative nature of their multifaceted methodology. Targeting the wallet is a favored tactic. When Rush Limbaugh used the word “slut” to describe an opponent they did not avail themselves of their constitutionally protected right to express an opinion about the distasteful, ignorant, and pointlessly personal nature of that slander. Instead, they organized a puerile campaign to intimidate the companies that advertised during his show into withdrawing their patronage. The very deliberate effect of this effort, had it been successful, would have been to silence Limbaugh completely. And all because the big mean man dared to utter a single syllable without first obtaining their consent.

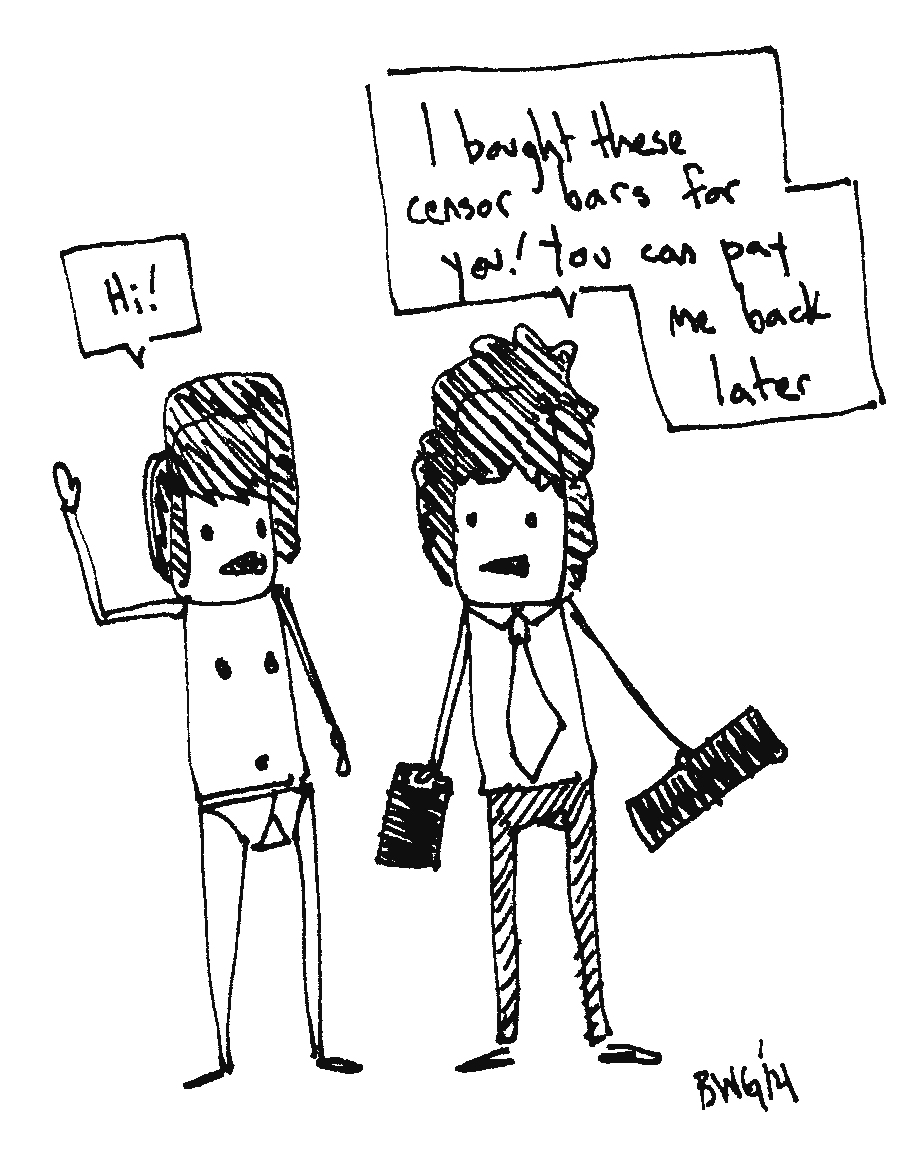

It is a common retort that Limbaugh could have used a different word just like the Danish cartoonist could have chosen not to depict Muhammad wearing a bomb turban. In either case, resort to a less “offensive” alternative would be tantamount to self-censorship. It was Limbaugh’s opinion that the woman in question was a “slut”; and it was the cartoonist’s impulse to feature Muhammad with an explosive on his head. Why should either person not have expressed himself fully and accurately and in precisely the way he desired?

The answer we are given is feeble to say the least. Because it would «offend» the faint of heart among us–people who, through sheer determination, are adept at discovering a way to be offended in any context; and who, lest we forget, retain the irrevocable right, as an intrinsic facet of their personal freedom and autonomy, to abstain from viewing or listening to the epithets in question.

When we remember this latter fact, the true motivation of the Offended is laid bare. It is not to assuage their hurt feelings that they seek to regulate the acceptable contours of free expression, for they can accomplish that task either by avoiding exposure or, more maturely, by exercising their own faculties to respond. It is rather to satisfy that eternal itch of human beings to control what their fellows think and say, how they are allowed to act, and so on.

That impulse could hardly be more contemptible or childish. But it is inexorable. It advances upon us in an avalanche of solipsism, fueled by mammals who are persuaded that as they wade through the wide world, with its billions of people and enormous diversity of thought and opinion, they retain a personal and sacrosanct right not to be offended by the thoughts or expressions of others; and that to fortify themselves against deprivations of that right, they are permitted to use intimidation to stifle all expression but what they find palatable. Nothing could be more «offensive» than that. Yet each and every time we are treated to a coerced and insincere «apology,» like the one eventually offered by Limbaugh to salvage his show, the Offended inch ever closer to victory in their crusade. Whether we value free speech and expression enough to prevent such a calamity is for us to decide.