The political divide between conservatives and liberals is growing increasingly bitter. Each side thinks that the other is evil. At the same time, a new currency is emerging within the eco-chambers of social media. It is the currency of outrage, and it is eroding our ability to listen to one another.

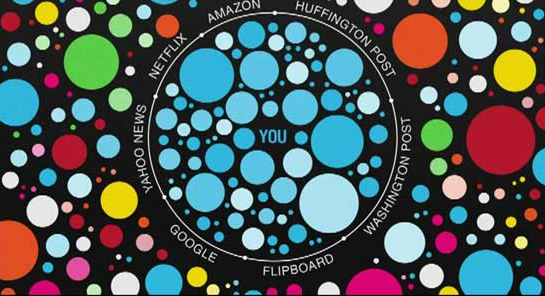

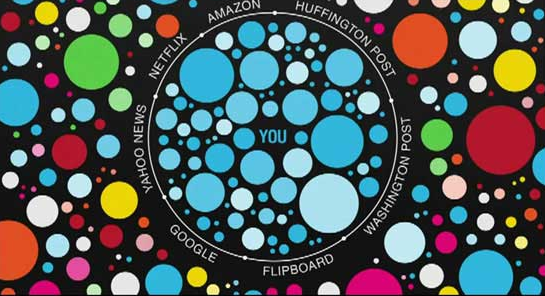

Those of us who follow news and commentary on Twitter flock together in groups according to our shared values and interests. On Facebook, algorithms selectively filter what we see based on our past search history, clicking behavior and friendship groups. The Twitter flocking bias and Facebook filter bubble have created eco-systems in which moral exhibitionism flourishes.

Because we are all interconnected within these online environments, we inevitably have our collective buttons pushed by skillful ‘outrage generators’ peddling a type of commentary designed for mass online circulation. When outrage pieces go viral, they capture gale-storms of righteous indignation converting outrage into clicks and cash.

Sharp-tongued columnists have always been a central part of the news media. But platforms such as Twitter have inspired new levels of hyperbole. Articles about morally-loaded topics trigger high-octane reactions in tweets, incentivizing writers to produce them. The writers inspire dozens to share their views in comments sections, where readers disagree with each other, fist-fighting with words. Herein lies the hook: after commenting, readers will return endlessly to view responses to their comments, driving page-view statistics. Of course, page-view statistics secure the advertising that subsidizes such platforms.

Clickbait bouncing off the walls within online echo chambers may seem relatively harmless. What does it matter if news merges with entertainment? What does it matter if political convictions are amplified? In the context of most people being politically apathetic, isn’t inspiring people to have stronger convictions a good thing?

Possibly not. Psychologists know that having political views that strongly oppose others’ has a gratifying and rewarding effect. It gratifies us because it allows us to feel as though we’re part of a team. It feels good for the simple reason that it helps us to feel connected and forget ourselves for a period of time—we become immersed in something larger. But at its most extreme, partisanship becomes psychologically addictive. It leads to fundamentalism and blind, unquestioning faith. This is the dark side of strong conviction.

Studying the moral psychology of political partisanship, Jonathan Haidt, Professor of Business Ethics at NYU, argues that we are fundamentally intuitive animals. Contrary to popular belief, moral decisions are made with emotion first, with reason occurring later. In The Righteous Mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion, Haidt argues that moral arguments are “mostly post-hoc constructions made up on the fly, crafted for strategic social aims.” It is a process driven by a very deep and unconscious need to belong. Outrage pieces exploit this psychology by fulfilling our evolved need to be part of a tribe, ready to defend our group or go into combat.

Social media, especially Twitter, has provided the architecture for pitting teams against each other. Those who shout the loudest often drown out expert opinion. Speed and anonymity have also changed the rules of engagement, making it easier to start heated arguments and making it less likely that bullying will carry consequences (such as a damaged reputation). The ability to comment or tweet immediately amplifies our impulsiveness, the enemy of cool-headed decision-making.

In an era in which social media provides the fuel for partisanship, online platforms are monetizing the flames. But they are also burning the bridges between us. We seem to have fewer shared goals. Our most pressing moral challenges are ones which require creative, long-term solutions of cooperation and commitment. Globally and locally, we face environmental calamities, rising economic inequality, and ageing populations. The need for bipartisan solutions has never been stronger.

Reinforcing bitterness between groups of people by invoking indignant outrage may be a good business strategy for online news outlets, but it is terrible for encouraging the social cohesion required to address problems facing our society . To foster cross-pollination of ideas, we need both to be aware and to listen. We should endeavor to avoid joining online digital mobs where we might throw verbal stones at anyone who may disagree with us. Ideally, we would consume a balance of information that both comforts us by adhering to our world-view and challenges us by expanding it.

It may also be possible for us to build better tools for social engagement, having our tribal and irrational psychological biases in mind. If we don’t like how our tools are working, we can always endeavor to engineer newer, better ones. But the issue is largely a cultural one, and there is no easy solution or quick answer.

Despite the promise of the Internet and social media to bring connectivity to our public discussions, we need to remain aware that we may actually be falling further apart.

Photo source here.