BY ISAAC LARA

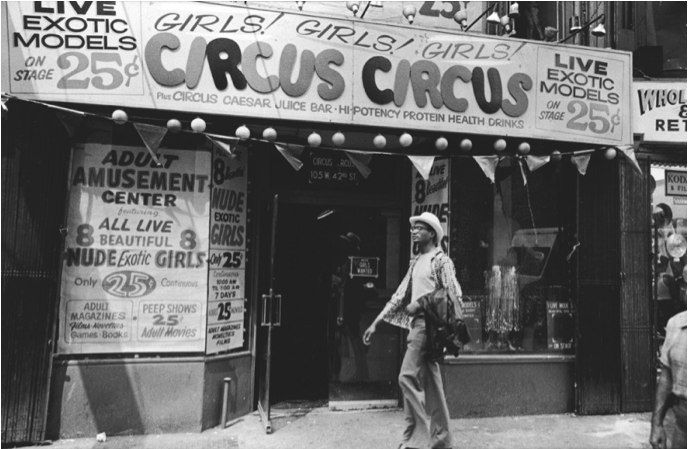

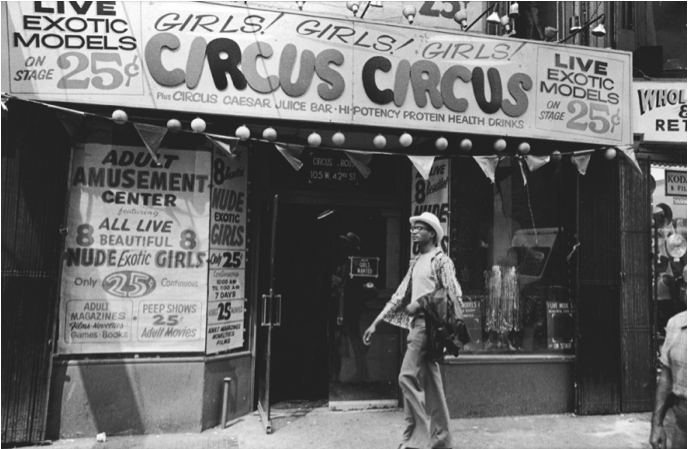

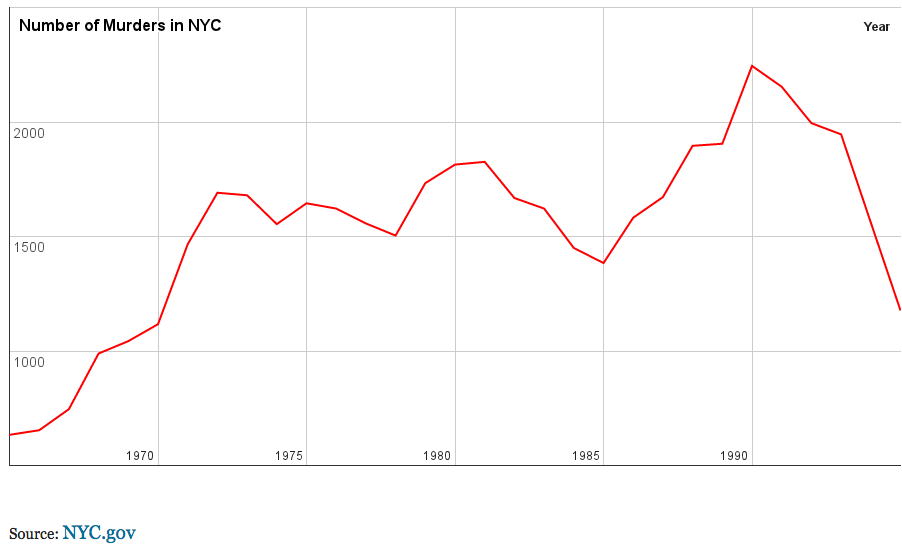

During the 1970s and 1980s, Times Square was not the tourist mecca that it is today. The now-glitzy area in Midtown’s theatre district had fallen into disrepair from decades of government negligence, with drug addicts and prostitutes prowling the streets. The few legal businesses that existed were mostly low-rent strip clubs and sordid adult entertainment video stores – not exactly the type to attract private investment. At one point an average New Yorker was at least six times more likely than in recent years to be murdered just walking down the street.[1]

Such startling statistics were emblematic of a larger criminal epidemic in New York City that was poisoning the local economy by driving commerce away from the area. After all, without public safety, civil society ceases to be an orderly space, undermining economic development. Times Square and other blighted areas represented massive liabilities for the City.

Searching for a Solution

Such challenges prompted innovative thinking around criminal justice. In 1994, Mayor Rudolph Giulani made enormous strides in combatting crime by implementing CompStat and handing its reins over to former (and current) NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton. For the first time ever, a major metropolitan police department would implement a data-driven management model designed to not only respond to crime, but also help prevent it by identifying large geographic locations where “hotspots” of crime normally arose. CompStat would enable precinct commanders to take preemptive action by stationing officers in said high-risk areas.

Over the years, the strategy proved successful, and Giulani and Bratton were credited with dramatically reducing the astronomical crime rates that plagued the administrations of Mayor David Dinkins and his predecessors. CompStat, in turn, was awarded numerous honors, including the 1996 Innovations in Government Award from the Kennedy School of Government, and replicated in cities nationwide.

Two decades of CompStat, however, have revealed its limitations. Instead of eliminating hotspots, the CompStat model merely reacts to them. While law enforcement agencies are now able to efficiently allocate their human and financial resources, they continue to inundate these areas with police officers without directly addressing the needs of these hotspots in the first place. Until recently, it was thought that their mere presence served to deter criminal behavior.

Operation Impact – the newly overhauled NYPD program – had once acted on the theory that officers reduced criminal activity. Before the DeBlasio Administration’s reforms, rookie officers used to be assigned to highly visible posts in distressed neighborhoods with the hopes of discouraging criminal behavior. By using police presence as a deterrent, though, the NYPD did not address the underlying problem, which is: What characteristics or community dynamics made these spots hot in the first place?

Answering that question could help mend police-community relations, especially in minority neighborhoods where residents have long complained of harassment by police. Thankfully, new advances in the field of criminal justice policy can help law enforcement agencies like the NYPD better understand those attitudes and qualities of urban environments that fuel hotspots.

Place Theory: A Comprehensive Approach

Instead of focusing primarily on criminal dispositions or on trends within a larger neighborhood area (à la CompStat), some criminal justice practitioners are now returning to the built environment as a factor in crime patterns. The study of crime prevention through environmental design, from which developed the “broken windows” theory of crime, is not new, but it has undergone several reiterations – the most recent of which includes “place theory.” Rather than focusing on larger neighborhoods, place theory targets smaller urban spaces where crime is highly concentrated, such as sidewalks, street corners, vacant buildings, or particular blocks and benches. By addressing the needs of confined urban spaces, proponents of place theory argue that crime can be reduced more effectively.

For this paradigm shift to be successful, planning departments and nonprofits should adhere to a three-pronged strategy. First is to promote natural surveillance by reducing shrubbery and vegetation that may block visibility, repairing broken streetlights, and opening or creating windows that face the street corners. Second is to repair any eyesores that may exist in the area, like cleaning up litter or erasing graffiti. Third is to install public amenities such as benches, water fountains, and playgrounds that may increase the area’s functionality. That could include reexamining the usage of vacant lots.

Taken together, these three steps could work in tandem to reduce the community’s reliance on police officers to deter criminal behavior. People, after all, don’t want to commit crimes in places where they will be easily seen, and even if they are willing to take the risk of being seen, they don’t want to do it in a place from which they derive pride and ownership.

Critics argue that a place-based policy approach may actually displace crime to another time or different part of the same neighborhood, but there’s no evidence for that. Professor David Weisburd, winner of the Stockholm Prize in Criminology, demonstrated through statistical analysis and ethnographic surveys of prostitution and drug activity in Jersey City, New Jersey that place-specific policies likely do not displace crime to other locations or other times.

Bringing Place Theory to the Bronx

In light of the theory’s benefits and extensive research support, the Center for Court Innovation – a public-private partnership dedicated to reforming criminal justice practices in New York City – will launch a place-based initiative in the South Bronx this summer. The project will specifically convene community stakeholders – including urban planners, residents, and community governing boards – to brainstorm tangible interventions informed by place theory for high-crime locations in the 40th and 44th Precincts.

The Center’s new initiative is one example of how criminal justice policy practitioners are challenging deeply held assumptions about how crime develops in cities. By pooling its resources and producing innovative solutions that address the needs of micro urban spaces, the Center is experimenting with a new policy approach that, if proven successful, could better improve public safety and the quality of life for city residents in the South Bronx and beyond.

Follow him at @IsaacGLara.

[1] 1990 murder rate: 30/100,000; 2012 murder rate: 5/100,000. Source: 2012 FBI Uniform Crime Reports.

Chart Source: Business Insider.

Photo Source: Sachs/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.