Between 2014 and 2015, Captagon made international headlines as a super drug fueling the Syrian Civil War. Fighters were supposedly using it in droves, and the sale of it funded various groups involved in the fighting. To an American or Western European audience, Captagon was an unknown entity. Drugs in the Middle East seemed paradoxical, with many highlighting the strict Islamic regulations concerning the taking of drugs and other intoxicants. Cultivation of opium in Afghanistan had been well documented, but it was generally assumed that drugs produced in the Middle East and its environs were destined for European and American markets, rather than the other way around. America and Europe were perceived to be barraged by narcotics, and the international community sought to restrict their unhindered transportation from one place to the next.

Captagon, otherwise known as fenethylline, is a combination of two drugs: theophylline and amphetamine. When taken in high doses the drug increases alertness, produces a feeling of euphoria, and reduces the need or desire for sleep and food. Captagon was widely used during the 1960s and 1970s to treat people with ADHD, narcolepsy, and depression, but was eventually banned in 1986 by the World Health Organization because of its addictive properties. Captagon abuse has been present in the Middle East for decades, with trafficking hubs located in Lebanon and Syria. The overwhelming majority of Captagon use is in the Arabian Peninsula – it is reportedly the most popular drug there, hooking 40% of young Saudi between the ages of 12 and 22 . One Saudi Prince in 2015 was even detained in Beirut after his private jet to Riyadh was discovered containing two tons of Captagon pills.

The UN world drugs report has repeatedly mentioned the increasing use and trafficking of Captagon since the 2000s, yet it was only in 2015 that the drug captivated the mainstream media due to its supposed use by jihadist groups, in particular Islamic State. Media outlets mentioned too how the production and sale of Captagon fueled numerous other organizations such as Hezbollah, components of the Free Syrian Army, and even the Assad regime.

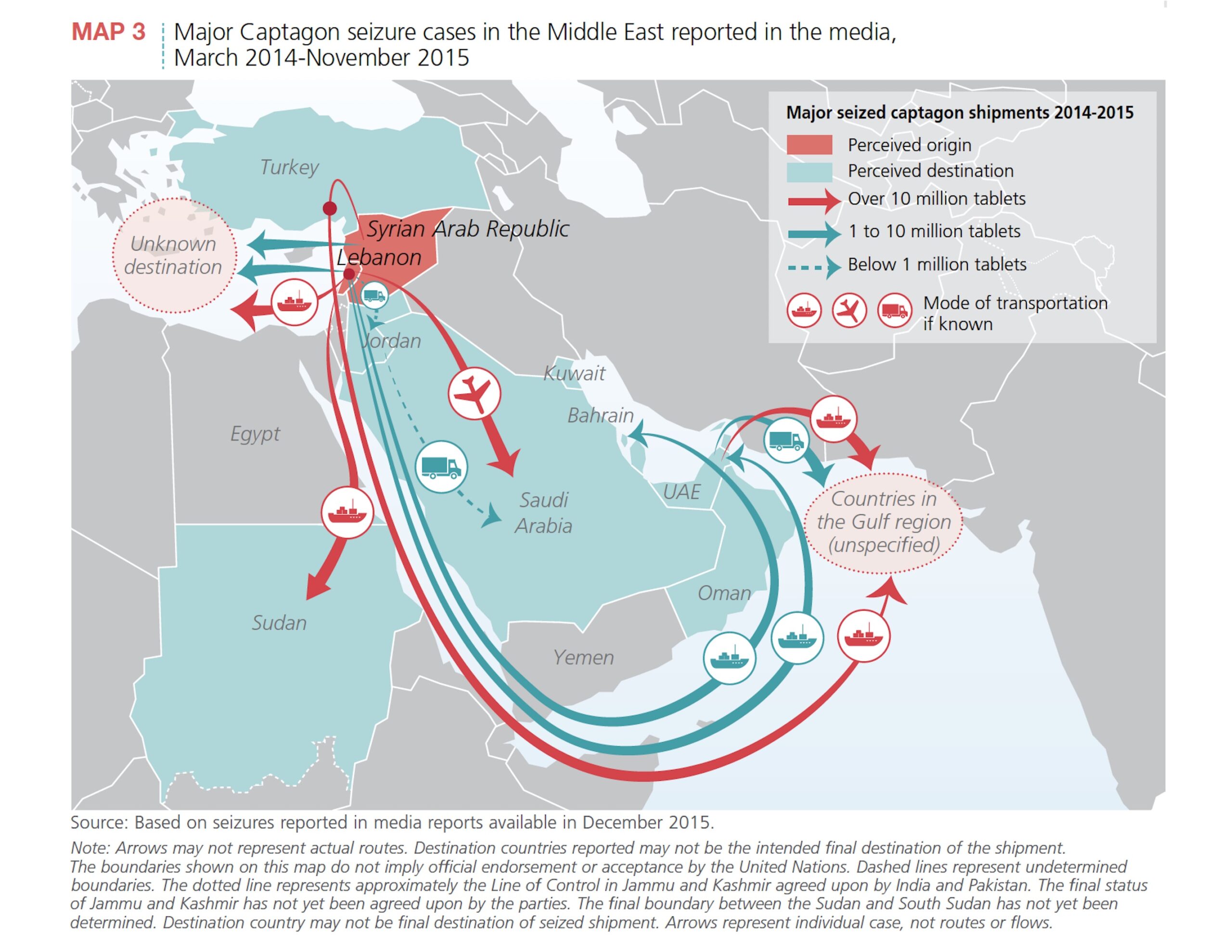

Captagon production centers moved to Syria after they closed in Lebanon. After the Syrian Civil War began, opportunists discovered a haven in a country with the infrastructure to create factories which could mass produce the drug. To this day there are not many available official figures regarding where and by whom it is produced. However, massive shipments of Captagon have been intercepted in Jordan and Lebanon and even as far as Turkey and the Gulf.

Most importantly however is how use of Captagon was alleged to correlate with the extreme violence characterizing the Syrian Civil War.

Above is a screenshot of a simple google search of the word “Captagon”. It is clear that many of the articles returned by the search intend to portray Captagon as a drug which transforms fighters into superhuman soldiers capable of very inhuman acts. In regards to jihadists, and specifically the Islamic State, the intent is even clearer. By portraying Captagon as a drug that induces psychosis and almost superhuman strength, it attempts to explain the use of extreme violence by groups like the Islamic State. Arguing that Captagon induces extreme energy and violence not only delegitimizes these groups, who supposedly contradict their strict religious beliefs by using the drug, it also provides an easy solution for ending that violence. The logic is simplified and made more straightforward: if one destroys the ideology and takes away the drugs, the violence will end. This is eerily similar to the discourse on counterterrorism championed by the current US administration. Terrorism is made into something which can be defeated, be it through military intervention or through repressing ideologies, while the root causes of the violence it generates are left unaddressed.

This fear of drug induced psychosis has its roots in the failed American War on Drugs. In the 1970s and 1980s the boogeyman of drugs was phencyclidine, or PCP. Fear of its effects in Los Angeles led many Los Angeles Police Department officers to use excessive chokehold techniques on predominantly black individuals, which resulted in at least sixteen deaths. PCP was rarely found in the systems of those murdered, yet the conjunction of a racist law enforcement agency and fear caused by the drug’s reported effects resulted in the loss of many innocent lives.

Interlacing drug use and extreme violence does little to address the root causes of violence, and is characteristic of the globally predominant contemporary drug policy: treat addicts as criminals and not as people who need help.

While the drug, like all amphetamines, suppresses the need to sleep and eat while reducing any paint felt, it is not a ‘jihadi super drug’ as some may suggest. In an interview with Live Science, Carl Hart, a Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at Columbia University, was asked if Captagon turned fighters into super-soldiers. He said, “In reality, its effects are nowhere near what the media reports have been talking about.” One ought to be wary of portrayals of Captagon as a superdrug. It is a type of amphetamine, and amphetamines have been present both in the Middle East and the rest of the world for decades. The side effects of amphetamines do indeed ruin lives, but they do not cause people to lose their inhibitions, and they certainly do not cause otherwise seemingly healthy individuals to commit acts of extreme brutality. Indeed, amphetamines have even been used by armies since the Second World War. The most recent cases show they were given to US Air Force pilots, albeit at much smaller regulated doses, during extended hours of operation during the first US-Iraq war. Indeed, if Captagon did have the ability to induce superhuman abilities, then one may confidently argue the United States military would be the first to use it.

The extreme violence associated with consumers of Captagon in the Syrian Civil War is better understood through analyzing the state violence and oppression widespread for decades under the Assad regime. While Captagon may imbue fighters with a sense of invincibility and allow them to operate on limited sleep, violence is not simply a side effect. Attributing violence only to drugs is a refusal to address the root causes of that violence and how it is perpetuated.