African states are increasingly leveraging the power of telecom operators to advance goals that the state itself struggles to secure (e.g. security and fiscal goals). This suggests a paradigmatic shift in African politics, whereby telecom operators have become a face of the state, exerting agency over state and citizen in pervasive and sometimes unexpected ways. However, their structural implications for African politics are lamentably under-theorised. Inspired by Marshall McLuhan’s maxim, “the medium is the message”, this paper examines MTN’s operations in Nigeria and Rwanda to expose the double-edged nature of this new structural dynamic.

By David Orr*

“Everywhere you go” boasts the slogan of South African telecom giant, MTN, a testament to its 232 million subscribers in eighteen African markets.[i] A powerful force on the continent, telecom providers offer transformative communication services to state and citizen alike. However, their pervasive reach calls into question the structural values embedded within these private actors, and the ensuing implications for African politics. It is therefore important to examine the oft-obfuscated structural changes that accompany the advent of new technology, rather than solely focusing on the tangible consequences of its implementation. Indeed, the maxim of the late Canadian philosopher, Marshall McLuhan, states that ‘the medium is the message’, thereby acknowledging that the characteristics of anything that is created (the medium) can be understood through the changes – either implicit or explicit – they effect (the message).[ii] Warning that the content of the medium “blinds us to the character of the medium”, the message thereby represents a mode of distraction away from the potent effect of the medium itself.[iii]

McLuhan’s adage resonates with the study of African politics for, as this paper argues, mobile telecommunication operators (‘telecom providers’) represent a new force in African politics. The actors providing telecom services (the medium) have significant repercussions for how the citizen engages with the state, establishing a need to move beyond the tangible message (digital communication capabilities) and examine their larger structural implications for African politics. Moreover, the pervasive reach and dependence associated with telecom providers suggests that they “are more than transmitters of content, they represent cultural ambitions, political machineries…and, in certain ways, the economy and spirit of an age”.[iv] Thus, this paper considers digital media as those actors who enable access: telecom providers. As the ultimate arbiters of providing the capital and infrastructure to construct these channels of communication, they require analysis to examine the implications of their emergence for African politics, respectively defined as the arenas within which citizens engage with the state.

The paper commences with an overview of the continent’s telecom landscape, followed by a historicising analysis of communication infrastructures for broadcasting state power. To situate the argument that telecom providers represent a novel form of corporate actor that informs how citizens engage with the state, the paper explores Nigeria and Rwanda’s harnessing of South African telecom giant MTN to advance state goals. The political implications of these state-led yet corporate-implemented logics highlight the strong dependency of both state and citizen on telecom providers, casting them as a face of the state. This suggests a paradigmatic shift in African politics whereby telecom providers are deeply intertwined with the state, yet also exert their own agency over state and citizen in pervasive and sometimes unexpected ways.

Why focus on the corporate actor?

This paper treats the corporate actor – specifically, telecom providers – as the key variable of analysis. However, the structural and political role of telecom providers is remarkably under-theorised in political economy examinations of information communication technologies (ICTs) in African states. Whilst a burgeoning literature analyses the impact of social media on African politics, minimal work has explored the political influence of the medium that offers citizens these services.[v] Although Obadare explores Nigerian citizens protesting telecom providers’ high tariffs, the article predominantly concerns the relationship between protestors and telecom providers, rather than the relationship between telecom providers and the state.[vi] This lacuna requires addressing, because corporate actors can considerably affect the crafting of regulation and political practices in Africa. For example, industry-led voluntary initiatives in Africa’s mining sector have seen regulatory decisions shift from the state to the corporate sphere, a phenomenon defined as private authority.[vii] Although this paper does not assume that state and citizen reliance on telecom providers presupposes diminished state sovereignty, it nevertheless treats telecom providers as a novel form of corporate actor¸ requiring analysis to examine the socio-political contours that accompany their existence.

Further underscoring the need to examine the corporate actor, Africa’s telecom industry is dominated by the private sector (save Ethiopia). Although many African states maintain a monopoly on fixed-line telephony services, penetration is low as infrastructure provision is both sporadic and expensive.[viii] By contrast, wireless mobile services require comparatively lower capital expenditure per user and are driven by multinational telecom providers. Historical logics help account for this wealth of private actors. A constitutive element of neoliberal policy prescriptions under World Bank structural adjustment policies (SAPs) and World Trade Organisation (WTO) guidelines, African states seeking financing were required to liberalise their economies and privatise state monopolies.[ix] Consequently, private telecom providers were licensed to provide telephony services that were once under the purview of the state.

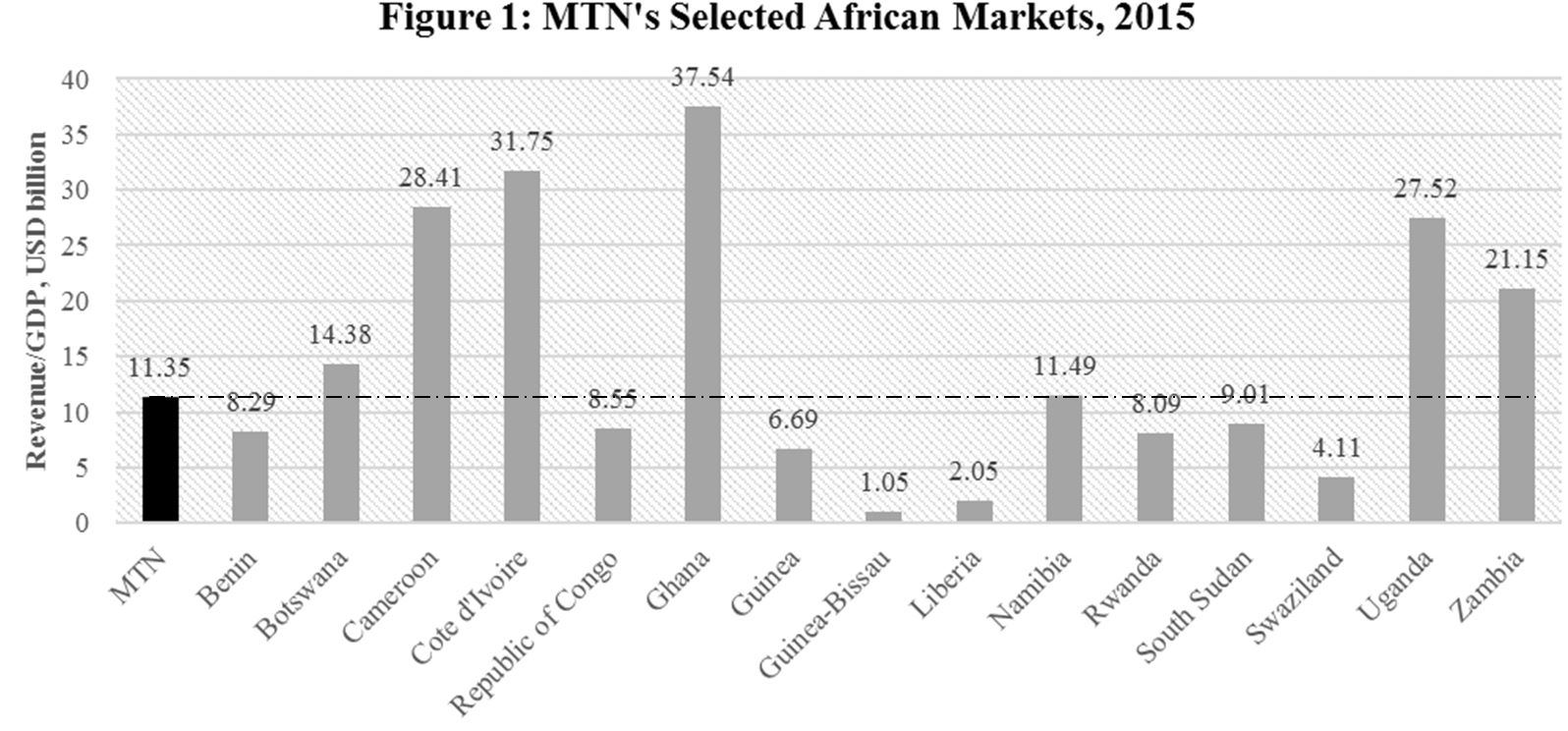

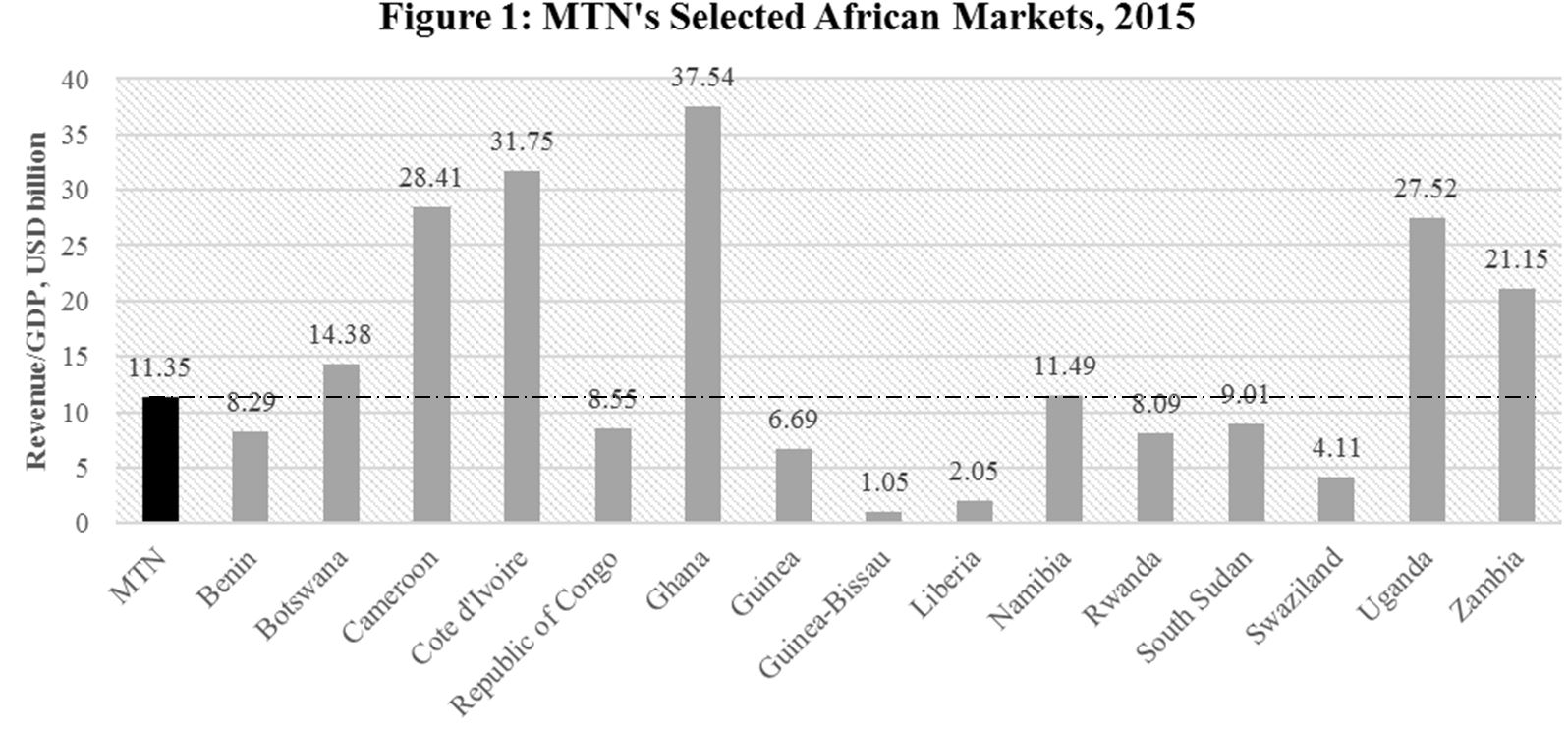

Accusations of economic imperialism have been levied against multinational corporations’ (MNCs) deep penetration in the African telecom market.[x] Ya’u argues that the WTO’s aim for telecom MNCs is to “secure the virgin markets of [developing states] and configure the world in the interest of new imperial powers”.[xi] These accusations merit investigation, particularly due to the asymmetrical capital differentials exhibited between foreign corporations and African states. As shown in Figure 1, South African telecom giant MTN had global revenues of $11.35 billion in 2015, exceeding the GDP of eight of its eighteen African markets.[xii] Thus, we should explore how these powerful actors engage with the state, and the ensuing implications for African politics.

Source: World Bank and MTN figures.[xiii]

Historicising communication technologies

The state’s use of communication infrastructures to broadcast power was not always so deeply intertwined with corporate actors. In preparation for analysing the contemporary era of private telecom providers, it is therefore necessary to examine communication technologies in the colonial and post-colonial eras. Although this approach belies Cooper’s claim that African history should be viewed fluidly, rather than demarked into colonial and post-colonial camps[xiv], the limited length of this paper renders Africa’s colonial era a feasible heuristic starting point.

European colonial powers transformed pre-colonial African states through centralised, export-oriented logics. To extend their rule, colonial authorities needed to establish order through bureaucratisation whilst also pacifying peripheral areas. However, Africa’s dispersed and ethnically-distinct populations challenged colonial authorities’ centralising ambitions. To conquer these difficult demographics, ‘modernising’ communication infrastructures were developed to broadcast state power; the novel innovations of the “telegraph and radio tied the superstructure together into a grid of domination [that was] not available in earlier centuries”.[xv] Although Herbst discounts the importance of communication for extending the reach of the state, he nevertheless concedes that infrastructure permitted the colonial state “to reach outward but also allow those in the hinterland to march more quickly to the centre of power”.[xvi] Communication networks were also seized for ‘civilising’ ambitions. Illustrating the representational power of colonial-era technological projects, Larkin notes that British colonial administrators in Nigeria adopted radio as a vehicle to craft subjects into developed, modern citizens.[xvii] However, the reflexive and subversive potential of communication networks also made transnational radio an ideal vehicle to disseminate subversive anti-colonial sentiments. For example, Egypt’s Radio Cairo broadcast anti-colonial programmes to British-ruled East Africa, mobilising liberation movements.[xviii]

Post-colonial governments inherited these communication networks and swiftly transformed them into a vehicle to disseminate a singular state-led narrative. Although the territorial sovereignty of African states’ colonially-constructed boundaries decreased inter-state warfare – a departure from European experiences where continuous aggression for trade and space made war inevitable – African states extended their power to prevent internal threats.[xix] Having experienced themselves the subversive power of radio during their liberation struggles, post-colonial states stifled communication channels that challenged their state-building initiatives.

The state’s monopolisation of information dissemination alludes to Cooper’s notion that post-colonial states serve a constraining ‘gatekeeper’ function.[xx] This practice was predominantly ‘top-down’, with little available recourse from subject populations because like “the radio, the newspaper is a medium better suited to sending messages than to receiving them”.[xxi] Indeed, radio offers an attractive vehicle to disseminate the contours of state policy. Attesting to the importance of monopolising communication mechanisms to broadcast state power, establishing control over state-owned radio was a preoccupation for militaries attempting coups across the continent. Radio was also used to propagate social ambitions. For example, former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere embraced communication technologies to advance his compulsory ujamaa ‘villagisation’ policy. Due to the extensive reach of radio broadcasts, Nyerere launched ujamaa via Tanzania’s state-owned radio station, and extolled its quantitative achievements through government-owned newspapers.[xxii] Further alluding to McLuhan’s argument that one should examine the medium to understand the message, communication infrastructures represent “the institutionalised networks that facilitate the flow of goods in a wider cultural as well as physical sense”.[xxiii] A veneer of modernity accompanied the state’s harnessing of communication technologies to pursue state goals, both a nod to cosmopolitanism and an entrenchment of post-colonial states’ new position in the world. In this way, state-led communication mechanisms were inextricably linked with how citizens experienced the state.

Resistive practices emerged to counter these ‘top-down’ state-broadcasting phenomena. Bayart challenges the notion that the state enjoyed a monopoly on crafting a singular narrative by arguing that “the state does not exist beyond the uses made of it by all social groups, including the most subordinate”.[xxiv] Invoking notions of Radio-Trottoir (pavement radio) and Radio-Couloir (corridor radio), he addresses the limits of the state’s extension of power vis-à-vis communication infrastructure. These informal word-of-mouth networks countered the dominant narrative, allowing citizens to “insolently ignore the embargoes of the censors and obstruct the totalitarian designs of the government…with their black humour”.[xxv] Although radio and newspapers were invariably one-way instruments, Bayart’s subversive ‘Radios’ underscore that citizens could deconstruct and repurpose these narratives, challenging post-colonial states’ centralising logics.

However, the liberalisation of communications infrastructure under SAP prescriptions fomented a stark departure from the state-monopolised communications nexus, and it is to the implications of this change for African politics that we now turn.

A novel form of corporate actor

The argument that telecom providers represent a new force for African politics rests on two assumptions. First is the notion of intimacy. The reach of telecom providers is unparalleled in the history of African politics; there were 557 million subscribers in 2015, a continent-wide penetration rate of 46%.[xxvi] As mentioned above, in the colonial and post-colonial period, the broadcasting of state power in Africa was predominantly through radio. Whilst radio remains the most accessible communication medium – some 70% of African households own a radio set – it is declining in importance and lacks the interactive component offered by telecom providers through voice, messaging, and internet services.[xxvii] As Rotberg and Aker contend, “the ubiquity, reach, and simplicity of mobile telephones” means that they “can receive information and its user can then cross-examine the conveyer of that information…in the absence of other low-cost communication devices, it is hardly surprising that mobile telephones have been widely adopted across the developing world”.[xxviii]

The intimacy of telecom providers with citizens – mobile phone users are inherently reliant on telecom providers – illustrates that foreign direct investment (FDI) by telecom providers is unique because of the number of citizens tangibly impacted. Whereas FDI projects in oil and mining also involve significant capital expenditure by MNCs, the impact of this investment is largely confined to local communities and the rents repatriated to the central government.[xxix] The mass penetration of mobile phones also points to Breckenridge’s notion that informational technologies do not only affect the lives of the wealthy, but rather that “the poor are in direct contact with cutting-edge technologies”.[xxx]

The second rationale concerns dependency by both state and citizen on telecom providers. Telecom providers offer significant economic gains for African states, with approximately $17 billion of tax raised before regulatory fees in 2015.[xxxi] Additionally, the telecom industry constituted 6.7% of the continent’s GDP in 2014, a figure predicted to expand to 7.6% by 2020.[xxxii] Many African states and neoliberal international organisations have also embraced telecom providers for state-building endeavours by constructing ICT for Development (‘ICT4D’) frameworks to seize the power of mobile communication and spur positive development outcomes.[xxxiii] In addition, the state relies on telecom providers to disseminate public safety announcements and for communication between government employees. Thus, telecom providers have constructed a new mode of politics “between the state and private companies, which increasingly handle many of the core activities of the state”.[xxxiv] Citizen dependence on telecom providers has also increased. As Pierskalla and Hollenbach contend, “mobile phones in Africa are often the only way for interpersonal, direct communication over distance”.[xxxv] Additionally, the ‘techno-optimist’ school expresses the benefits of mobile telephony in market terms, with positive relationships having been established between increased network coverage and enhanced market efficiency.[xxxvi] Regardless of the precise extent to which telephone providers have spurred economic growth, it is clear that African citizens and states are deeply reliant on telecom providers for this “opium of the people”.[xxxvii]

The broad reach of telecom providers, coupled by the state’s deeply intertwined relationship with them to effect certain state-led logics, means that the state engages in a more intimate manner with telecom providers than other corporate actors. Alluding to McLuhan’s adage, this ‘medium’ posits a significant structural shift in African politics, for a new form of politics has emerged whereby private firms increasingly handle many of the core activities of the state. With both public and private sector dependent on the mobile networks functioning smoothly, the state’s growing reliance on telecom providers to deliver services underscores that the latter have become a mode by which citizens experience the state. This challenges Cooper’s contention that post-colonial states inherited colonial-era ‘gatekeeper’ mechanisms to enforce order and distribute resources.[xxxviii] Although state-linked telecom regulators entertain some agency when engaging with telecom providers, such as the provision of operating licenses, the latter’s socio-economic influence highlights the growing power of private actors to control “the interface of national and world economies”, a realm traditionally the preserve of the state.[xxxix] Whilst telecom providers are not the first corporate actor to exploit this structural adaption, the deep dependency exhibited by both state and citizen, coupled by their intimate reach, casts telecom providers as a powerful and novel corporate actor with which the state must increasingly act in concert.

MTN in Nigeria and Rwanda

Case studies of the South African telecom giant MTN in its Nigerian and Rwandan markets situate the extensive dependency of state and citizen on telecom providers, and highlights that citizens perceive these private actors as a new face of the state. With global revenues of $11.35 billion in 2015, 232 million subscribers, and operations in 22 countries, MTN is one of Africa’s largest telecom providers.[xl] Founded in 1994, MTN entered Nigeria and Rwanda in 2001 and 1998 respectively, following the liberalisation of their telecom markets.[xli] Whereas Nigeria’s telecom market is heavily liberalised, Rwanda’s telecom sector is deeply informed by state-directed logics geared towards its ‘Vision 2020’ programme to become a knowledge-based economy. MTN has the largest subscriber base in both states, and in 2015 employed capital expenditure projects of $852 million in Nigeria; figures for Rwanda are not published.[xlii] Sutherland notes that MTN entered Nigeria using an empowerment model, whereby shares were provided to politically-influential individuals in exchange for assurances that its license would not be revoked.[xliii] Similarly in Rwanda, MTN’s initial partnership with the governing party’s investment arm, Tri-Star/CVL, illustrates the deeply interconnected relationship between telecom MNCs and African states.[xliv]

Beyond its financial clout, other factors render MTN worthy of investigation. The company has had a rocky relationship with the Nigerian government, with allegations of poor regulatory compliance and corruption; Sutherland contends that in Nigeria, “MTN gave stock to presidential cronies to secure licenses”.[xlv] By contrast, Rwanda’s ICT4D strategy has seen the state enjoy a more positive relationship with MTN as they work in partnership to realise this prerogative. Thus, exploring MTN-Rwanda offers an indication of how a strong state engages with an MNC whose revenue is higher than its GDP (see Figure 1). Analysing MTN-Nigeria and MTN-Rwanda also assesses the extent to which this paper’s framing of telecom providers as a new corporate actor can be transported to diverse operating environments in Africa. Finally, as a Southern MNC, MTN affords an examination of South-South flows of FDI and the extent to which accusations of ‘electronic imperialism’ can be levied against African MNCs.

MTN-Nigeria: Security

In May 2013, the Nigerian government barred mobile telecom services in three north-eastern states. Premised on the belief that insurgents from the terrorist group Boko Haram were using unregistered SIM cards to coordinate attacks, Nigeria’s four telecom operators, including MTN, were prevented from operating for four months and a state of emergency was declared. Although the government considered the shutdown a military success, it was criticised heavily by citizens who felt that the state deprived them of a vital service, unleashing calls of state illegitimacy.[xlvi] Citizens’ anger was not directed at telecom providers, but rather towards the state, implying that the state’s use of powerful private actors to pursue state goals informs how citizens experience the state. Indeed, Nigeria’s harnessing of private actors to pursue state security goals points to the notion that, relative to the state, telecom providers command a greater reach over Nigerian citizens.

MTN’s engagement with the Nigerian state during this period extended beyond shutting down services. In the preceding two years, MTN was required by the government-aligned Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) to register customers’ SIM cards to mitigate the threat from Boko Haram.[xlvii] However, MTN failed to comply with the June 2015 deadline. The NCC charged that MTN had failed to register 5.2 million SIM cards, and was thus complicit in both contravening regulatory requirements and posing a security threat. MTN was slapped with a $5.2 billion fine by the NCC, the largest fine ever levied in Africa.[xlviii] MTN’s malfeasance extended to the diplomatic realm when Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari declared, during a state visit by South African President Jacob Zuma, that MTN’s failure to register SIM cards resulted in the deaths of 10,000 Nigerians.[xlix] Illustrating the negotiating power of telecom providers, MTN challenged the legality of the fine and even threatened to pull out of Nigeria, threatening to deprive the state of one of its largest taxpayers.[l] Ultimately, the fine was reduced to $1.6 billion and MTN received a renewed license to extend its 4G services, thereby raising the question of the extent to which the politics of money can supersede national security concerns.[li]

MTN-Rwanda: Taxation

Aligning with Rwanda’s digitally-informed Vision 2020 framework, the state has harnessed MTN-Rwanda’s technological expertise and penetration to improve its tax collection procedures. In December 2016, MTN and the Rwanda Revenue Authority (RRA) launched an initiative via MTN’s Mobile Money (electronic wallet) platform to “ease the process and reduce the cost of doing business in the country”.[lii] Under the scheme, taxpayers can transfer funds directly to the RRA from their Mobile Money accounts, with MTN earning a premium for facilitating the transfer. With 85% of MTN’s 4.1 million customers already using Mobile Money, MTN represents an ideal partner for the Rwandan state to improve its tax accrual methods.[liii]

However, the MTN-RRA partnership has implications for telecom providers’ role in African politics. Not only is the MTN-RRA partnership a mode to enhance state revenue, it also harbours moralising and modernising elements by incentivising citizens to fulfil their civic duties. MTN’s statement that subscribers must no longer take time off “to honour their civic obligations” and “can pay their taxes from…any remote location outside the premises of RRA”[liv] resonates with Larkin’s argument that colonial authorities embraced communication technologies to ‘modernise’ their subjects.[lv] Attesting to the reach of telecom providers relative to the state, this programme illustrates that, like Nigeria, the Rwandan state is leveraging the power of telecom providers to advance goals that the state itself struggles to secure. The MTN-RRA partnership also offers the Rwandan state a greater capacity to identify who has paid taxes, alluding to Scott’s notion that the state inherently seeks to extend its power by simplifying its population through bureaucracy.[lvi] This is particularly salient in Rwanda, which Purdeková argues has been operating an extensive state-led surveillance apparatus since the pre-colonial period.[lvii] The fundamental difference between the MTN-RRA partnership and previous eras, however, is that telecom providers are now a crucial vehicle to realise this goal.

African politics and telecom providers: A double-edged sword

As per McLuhan, MTN’s experiences in Nigeria and Rwanda reveal that the medium of the telecom provider has a powerful message for African politics. No other private actor commands an equivalent degree of reach and dependence by both state and citizen. It is perhaps unsurprising then that African states harness the power of telecom providers to advance state goals such as security and tax collection. This resonates with Herbst’s contention that colonial and post-colonial states constructed communication infrastructure to broadcast state power and achieve logics of centralisation.[lviii] However, the crucial amendment in this scenario regards who controls these processes. Whilst radio and communication infrastructures during these periods were the preserve of the state, private telecom providers now challenge this position. State logics are no longer singularly effected by the state, but rather in concert with private actors.

In the examples offered above, despite being deeply intertwined with state-led logics of security and tax accrual and relying on state regulators to maintain its license to operate, MTN exerts considerable agency in its cooperation with the state. This agential qualification underscores McLuhan’s notion that the medium itself must be examined to interpret the structural shifts effected by the message. MTN’s failure to register SIM cards denied the Nigerian state an individual identification of citizens (including potential terrorists) – a goal Scott argues is crucial for broadcasting state power[lix] – ostensibly causing thousands of deaths. Although MTN was fined, this transgression nevertheless underlines that the state engages in a more intimate relationship with this novel force of corporate actor than ever before, and illustrates the extensive dependency of the state on telecom providers. The considerable reduction in the fine, coupled by Nigeria’s plea that MTN not leave the market, highlights the negotiating power exercised by MTN over the Nigerian state. Unfortunately, however, the negotiating relationships between African states and telecom providers are opaque and deeply under-theorised in the literature, so MTN’s influence must be implied rather than being made explicit. Nevertheless, the contours of these negotiating relationships should spur further study, particularly because MTN’s asymmetrical financial advantage is only exacerbated in the poorer states outlined in Figure 1.

The state’s use of telecom providers to realise particular goals also illustrates that telecom providers have become a new face of the state, with deep implications for African politics. Although the Rwandan case study suggests that MTN-state collaboration can enhance state efficiency, the uproar following MTN’s shutdown in north-eastern Nigeria highlights citizens’ dependence on telecom providers. If the state shuts off access to this medium, this can lead to protests and challenge the legitimacy of the state. MTN’s actions thereby point to a deep structural shift and a new manifestation of politics between the state and private actors that increasingly handle many of the core activities of the state.[lx] Whilst national regulators can constrain certain ambitions, the deep dependency that citizens and states exhibit towards telecom providers highlights that African states must increasingly act in concert with telecom providers. Although the state maintains sovereign power, it nevertheless validates the importance of telecom providers by exploiting their services to counter what the state perceives as a threat. Thus, the harnessing of communication infrastructure to broadcast power is no longer the preserve of the state, but rather deeply interwoven with the distinct interests of private telecom providers.

Indeed, it is important to consider the divergent motivations between state and corporation, and the ensuing implications for African politics. Telecom providers are not guided by social emancipation but rather by a fiduciary duty to enhance profits for shareholders. A key driver for MTN is growing its customer base; in doing so, spaces for mobilisation proliferate, with repercussions for democratisation. Like the subversive ‘Radios’ noted by Bayart[lxi], telecom providers can, in the absence of severe state censorship, enable access to social media, offering citizens a new vehicle to construct alliances, critique state policy, and mobilise for change. For example, the rise of MTN social media bundles to attract customers offers a foil to the ‘top-down’ broadcasting practices that characterised how the state engaged with citizens.[lxii] Although the extent to which social media can spur democratic change is beyond the scope of this paper, telecom providers nevertheless establish a pervasive medium for interactive communication that the state’s radio and fixed-line telephony services cannot. Whilst we should be cautious in ascribing considerable causal power to social media for enhancing democracy, telecom providers offer both citizens and opposition actors a new platform that can be leveraged for democratisation.

Thus, the advent of telecom providers represents a double-edged sword for African states. Positively, they can be harnessed to pursue emancipatory development and security outcomes. However, because telecom providers represent a new face by which citizens experience the state, the perceived misuse of these actors can challenge state legitimacy. The reach and extensive dependency of state and citizen on telecom providers highlights that the distribution and consumption of communication has been fundamentally altered, illustrating that this medium – a corporate actor with pervasive political salience – has a powerful message for African politics. Today’s broadcasting of state power in Africa exists to a considerable extent in conjunction with agency-wielding private actors, a novel phenomenon for postcolonial states whose broadcasting mediums traditionally enjoyed a monopoly on the distribution of information. Although the importance of telecom providers does not necessarily decrease the state’s capacity to broadcast state power, the state’s strong dependence on telecom providers means that they must adapt to not only the decentralising and democratising implications afforded by the onset of these actors, but also the innovation and agency exhibited by the telecom provider itself. These findings raise intriguing questions for further study: to what extent are telecom providers eroding state sovereignty? Is state and citizen dependence on telecom providers irreversible? Is if useful for the state to view citizens as consumers? With African states transitioning to digitally-informed modes of governance and mobile phone subscriptions booming across the continent, the need to examine telecom providers’ message for African politics has become more acute than ever before.

[i] MTN Group Ltd., “MTN Rwanda introduces tax payment services using MTN Mobile Money,” 2016, available from http://www.mtn.co.rw/Content/Pages/359/MTN_Rwanda_introduces_tax_payment_ services_using_MTN_Mobile_Money, accessed March 21, 2017.

[ii] Mark Federman, “What is the Meaning of the Medium is the Message?”, 2004, available from http://individual.utoronto.ca/markfederman/MeaningTheMediumistheMessage.pdf, accessed March 20, 2017.

[iii] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw Hill, 1964), 9.

[iv] Brian Larkin, Signal and noise: media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 2.

[v] see Chambi Chachage, “From Citizenship to Netizenship: Blogging for social change in Tanzania,” Development 53, no. 3 (2010): 429-432; and Allison Hahn, “Live from the pastures: Maasai YouTube protest videos,” Media, Culture & Society 38, no. 8 (2016): 1236-1246.

[vi] Ebenezer Obadare, “Playing politics with the mobile phone in Nigeria: civil society, big business & the state,” Review of African political economy 33, no. 107 (2006): 93-111.

[vii] Hevina Dashwood, The rise of global corporate social responsibility: Mining and the spread of global norms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

[viii] BMI Business Monitor International, Rwanda Telecommunications Report Q2 2017, (London: Business Monitor International, 2017), 13.

[ix] Yunusa Ya’u, “The new imperialism & Africa in the global electronic village,” Review of African political economy 31, no. 99 (2004): 24.

[x] James Murphy, Pádraig Carmody, and Björn Surborg, “Industrial transformation or business as usual? Information and communication technologies and Africa’s place in the global information economy,” Review of African Political Economy 41, no. 140 (2014): 264-283.

[xi] Yunusa Ya’u, “The new imperialism & Africa in the global electronic village,” Review of African political economy 31, no. 99 (2004): 11.

[xii] MTN Group Ltd., “Financial Results 2016”, MTN Group Ltd., 2016, p.14, available from https://www.mtn.com/MTN%20Service%20Detail%20Annual%20Reports1/booklet.pdf, accessed March 6, 2017.

[xiii] World Bank, “World Development Indicators Database,” 2016, available from http://api.worldbank.org/v2/en/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?downloadformat=xml, accessed March 6, 2017.

MTN Group Ltd., “Financial Results 2016”, MTN Group Ltd., 2016, p.14, available from https://www.mtn.com/MTN%20Service%20Detail%20Annual%20Reports1/booklet.pdf, accessed March 6, 2017.

[xiv] Frederick Cooper, Africa since 1940: the past of the present, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[xv] Crawford Young, The African colonial state in comparative perspective (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994), 280.

[xvi] Jeffrey Herbst, States and power in Africa: Comparative lessons in authority and control (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 170.

[xvii] Brian Larkin, Signal and noise: media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008).

[xviii] James Brennan, “Poison and Dope: Radio and the art of political incentive in East Africa, 1940- 1965”, Proceedings from African Studies Center Seminar, University of Leiden, Leiden, 2008.

[xix] Robert Jackson, Quasi-states: sovereignty, international relations and the Third World (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993); and Jeffrey Herbst, States and power in Africa: Comparative lessons in authority and control (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

[xx] Frederick Cooper, Africa since 1940: the past of the present, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[xxi] James Scott, Seeing like a state: How some schemes to improve the human condition have failed, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998), 155.

[xxii] Ibid., 409.

[xxiii] Brian Larkin, Signal and noise: media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 5.

[xxiv] Jean-Francois Bayart, The state in Africa: The politics of the belly (London: Polity Press, 2009), 252.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] GSMA Ltd., “The Mobile Economy: Africa 2016,” GSMA Ltd., 2016, p.8, available from https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/?file=3bc21ea879a5b217b64d62fa24c55bdf&download, accessed March 28, 2017.

[xxvii] Afrobarometer, “Tech trends in the African news media space,” Afrobarometer 2015, available from http://afrobarometer.org/blogs/tech-trends-african-news-media-space, accessed March 27, 2017.

[xxviii] Robert Rotberg and Jenny Aker, “Mobile phones: uplifting weak and failed states,” The Washington Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2013): 113.

[xxix] Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, Oil and Politics in the Gulf of Guinea, (London: Hurst, 2007).

[xxx] Keith Breckenridge, “The biometric state: The promise and peril of digital government in the new South Africa,” Journal of Southern African Studies 31, no. 2 (2005): 282.

[xxxi] GSMA Ltd., “The Mobile Economy: Africa 2016,” GSMA Ltd., 2016, p.9, available from https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/?file=3bc21ea879a5b217b64d62fa24c55bdf&download, accessed March 28, 2017.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] See Geoff Walsham, “ICT4D research: reflections on history and future agenda,” Information Technology for Development 23, no. 1 (2017): 18-41.

[xxxiv] Keith Breckenridge, “The biometric state: The promise and peril of digital government in the new South Africa,” Journal of Southern African Studies 31, no. 2 (2005): 274.

[xxxv] Jan Pierskalla, and Florian Hollenbach, “Technology and collective action: The effect of cell phone coverage on political violence in Africa,” American Political Science Review 107, no. 2 (2013): 208.

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] Ebenezer Obadare, “Playing politics with the mobile phone in Nigeria: civil society, big business & the state,” Review of African political economy 33, no. 107 (2006): 93-111.

[xxxviii] Frederick Cooper, Africa since 1940: the past of the present, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[xxxix] Ibid., 141.

[xl] MTN Group Ltd., “Financial Results 2016”, MTN Group Ltd., 2016, available from https://www.mtn.com/MTN%20Service%20Detail%20Annual%20Reports1/booklet.pdf, accessed March 6, 2017.

[xli] Ewan Sutherland, “MTN: A South African mobile telecommunications group in Africa and Asia,” Communicatio 41, no. 4 (2015): 471.

[xlii] MTN Group Ltd., “Financial Results 2016”, MTN Group Ltd., 2016, p.11, available from https://www.mtn.com/MTN%20Service%20Detail%20Annual%20Reports1/booklet.pdf, accessed March 6, 2017.

[xliii] Ewan Sutherland, “MTN: A South African mobile telecommunications group in Africa and Asia,” Communicatio 41, no. 4 (2015): 479.

[xliv] David Booth, and Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, “Developmental patrimonialism? The case of Rwanda,” African Affairs 111, no. 444 (2012): 389.

[xlv] Ewan Sutherland, “MTN: A South African mobile telecommunications group in Africa and Asia,” Communicatio 41, no. 4 (2015): 497.

[xlvi] Jacob Jacob, and Idorenyin Akpan, “Silencing Boko Haram: Mobile Phone Blackout and Counterinsurgency in Nigeria’s Northeast region,” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 4, no. 1 (2015): 1-17.

[xlvii] BMI Business Monitor International, Nigeria Telecommunications Report Q1 2017, (London: Business Monitor International, 2017).

[xlviii] Ibid.

[xlix] BBC News, “Nigeria’s Buhari says MTN fuelled Boko Haram insurgency,” March 8, 2016, available from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-35755298, accessed March 19, 2017.

[l] PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2014). Nigeria Could Lose Over 5 Trillion Naira in Tax Revenue if the bill seeking to compel private companies to become public entities is enacted into law,” 2014, available from https://www.pwc.com/ng/en/assets/pdf/tax-watch-october-2014.pdf, accessed March 30, 2017.

[li] BMI Business Monitor International, Nigeria Telecommunications Report Q1 2017, (London: Business Monitor International, 2017): 55.

[lii] BMI Business Monitor International, Rwanda Telecommunications Report Q2 2017, (London: Business Monitor International, 2017), 28.

[liii] Ibid., 38.

[liv] MTN Group Ltd., “MTN Rwanda introduces tax payment services using MTN Mobile Money,” 2016, available from http://www.mtn.co.rw/Content/Pages/359/MTN_Rwanda_introduces_tax_payment_services_using_MTN_Mobile_Money, accessed March 21, 2017.

[lv] Brian Larkin, Signal and noise: media, infrastructure, and urban culture in Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008).

[lvi] James Scott, Seeing like a state: How some schemes to improve the human condition have failed, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998).

[lvii] Purdeková, Andrea. ““Mundane Sights” of Power: The History of Social Monitoring and Its Subversion in Rwanda.” African Studies Review 59, no. 2 (2016): 59-86.

[lviii] Jeffrey Herbst, States and power in Africa: Comparative lessons in authority and control (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

[lix] James Scott, Seeing like a state: How some schemes to improve the human condition have failed, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998).

[lx] Keith Breckenridge, “The biometric state: The promise and peril of digital government in the new South Africa,” Journal of Southern African Studies 31, no. 2 (2005).

[lxi] Jean-Francois Bayart, The state in Africa: The politics of the belly (London: Polity Press, 2009).

[lxii] see Wendy Willems, “Social media, platform power and (mis)information in Zambia’s recent elections,” Africa at LSE blog post, August 3, 2016, available from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2016/08/30/social-media-platform-power-and-misinformation-in-zambias-recent-elections, accessed March 20, 2017.