In March 2018, President Trump stated that ‘trade wars are good, and easy to win’ as he sparked a trade war with China to fight what he called the country’s unfair bilateral trade balance and intellectual property theft. The trade war has taken longer than expected to “win,” especially as rhetoric on both sides heats up. Recent aggressive actions by the US, followed by China’s currency devaluation and Secretary Mnuchin’s labeling China a ‘currency manipulator’ have wreaked havoc on financial markets and have injected uncertainty into the economy.

To date, the trade war has been difficult for both the United States and China, costing the economies nearly $360 billion combined. These tariffs are bad for both American and Chinese businesses. Without a bolder negotiation strategy, the US-China trade war will begin to harm other connected economies as well.

Diplomacy Should Prevail

The US and China must take action through diplomatic means to end this damaging state of economic affairs. A traditional definition suggests that trade or commercial diplomacy (CDC) is an activity conducted by state representatives with diplomatic status to promote business between a home and host country. In addition, a widely known principle for successful negotiations is ‘reciprocity’, obtaining concessions by giving up concessions of a similar scale. The U.S. and China should use trade diplomacy at the WTO level to reach an agreement that both sides can support for three reasons.

First, the United States and China rely on one another. China is the second largest economic power in the world. It has been the largest exporter of goods since 2007 and has been the largest supplier of goods to the U.S. since 2003. China has achieved all of this without a free trade agreement with the U.S. The use of trade diplomacy might be appropriate for the U.S. to protect its global leadership and secure its imports. By taking a similar path, China would invigorate its rising geopolitical influence.

Second, the international community does not stand by the United States’ increasing use of tariffs to achieve economic and political outcomes. The U.S. faces several WTO claims, filed by China, the E.U., Russia, Canada, and other members, against the import restrictions the U.S. adopted on steel and aluminum in 2018 on the grounds of national security concerns. They argue – correctly – that those restrictions are illegal as they disregard the requisites for the adoption of security exceptions. Interestingly, a recent WTO panel’s first substantive ruling on security exceptions might critically weaken the U.S.’s arguments and lead to defeat at WTO. Hence, the U.S. has an incentive to embrace negotiations or withstand a public loss.

Third, recent WTO actions by China might already signal a path forward for negotiations. China had previously filed WTO cases against the U.S. and EU for price comparison methodologies that both entities use when adopting trade remedy measures against Chinese imports. However, China recently requested to suspend proceedings on the EU’s case since reliable WTO sources revealed that the final ruling would be likely to hurt China. Losing such a pivotal case in the trade of goods should be a compelling incentive for China to negotiate within the WTO. Given that a similar ruling is likely in the identical case against the US, China has incentive to withdraw from the US case. This could further serve as a de-escalation mechanism. This would exemplify the mutual concessions approach of trade diplomacy, under which China would agree to open select economic sectors in exchange for better treatment in trade remedy measures.

Avenues to Consider

After weak previous attempts to end the current US-China trade war, this year’s G-20 summit in Japan brought about a new opportunity to resume trade talks. However, the recent escalations by both the US and China frustrate a prompt solution.

Moving forward, the U.S. and China have three choices.

The first is to undergo a broader negotiation at the WTO on China’s fundamental economic model. That is, the underlying roots of the current conflict can be found in a Chinese political and Communist Party driven economic model that clashes with the western capitalist vision. A bilateral agreement between the US and China (such as China promising to buy some agricultural goods and not stealing intellectual property) won’t suffice in the medium- and long- term. Key related aspects of the Chinese economic model, such as its approach towards taxation, state owned enterprises, price controls, state subsidies, agriculture, and financial services, were addressed by China’s compromises as enshrined in China’s Protocol of Accession to the WTO in 2001. Essentially, the purpose was to incentivize China to lower or eliminate trade barriers so it behaves like the other WTO members abiding by the standard rules of the multilateral trading system.

However, if the 2001 obligations of the multilateral Protocol seem not to have been met by China in recent last years, it is unlikely that China will choose to compromise during bilateral talks and thereby accede power to the US. Therefore, these trade talks would be futile.

Under a second approach, the US and China could participate in multilateral negotiations at the WTO. This option is more legitimate and pragmatic. If the U.S. wants China to enact substantive policy change, the U.S. will need support from the remaining WTO members to place pressure on China as part of a multilateral negotiation where clearer and measurable commitments can be agreed upon. China would need to hold candid discussions and reach solid agreements on its economic model to liberalize trade. In turn, the U.S. and the remaining WTO members would need to agree to impose less restrictive treatments on China within the trading system.

The final choice is simpler. The US and China may continue on their current path, leaving citizens and businesses to suffer the likely negative consequences.

The US-China trade war needs to end before it wreaks further havoc on the global economy. Multilateral negotiations at the WTO present the most feasible approach to do so. The decision to engage is in both the U.S.’ and China’s hands. Now is the time to act.

Luis C. Ramírez is a lawyer with expertise in international economic law. He holds an LL.M in International Law from The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, and works as a foreign associate with the International Trade Practice of a law firm in Washington, D.C. These opinions remain entirely the author’s and do not reflect those of said law firm. Contact: luisc.ramirezm@gmail.com.

Edited by: Hilary Gelfond

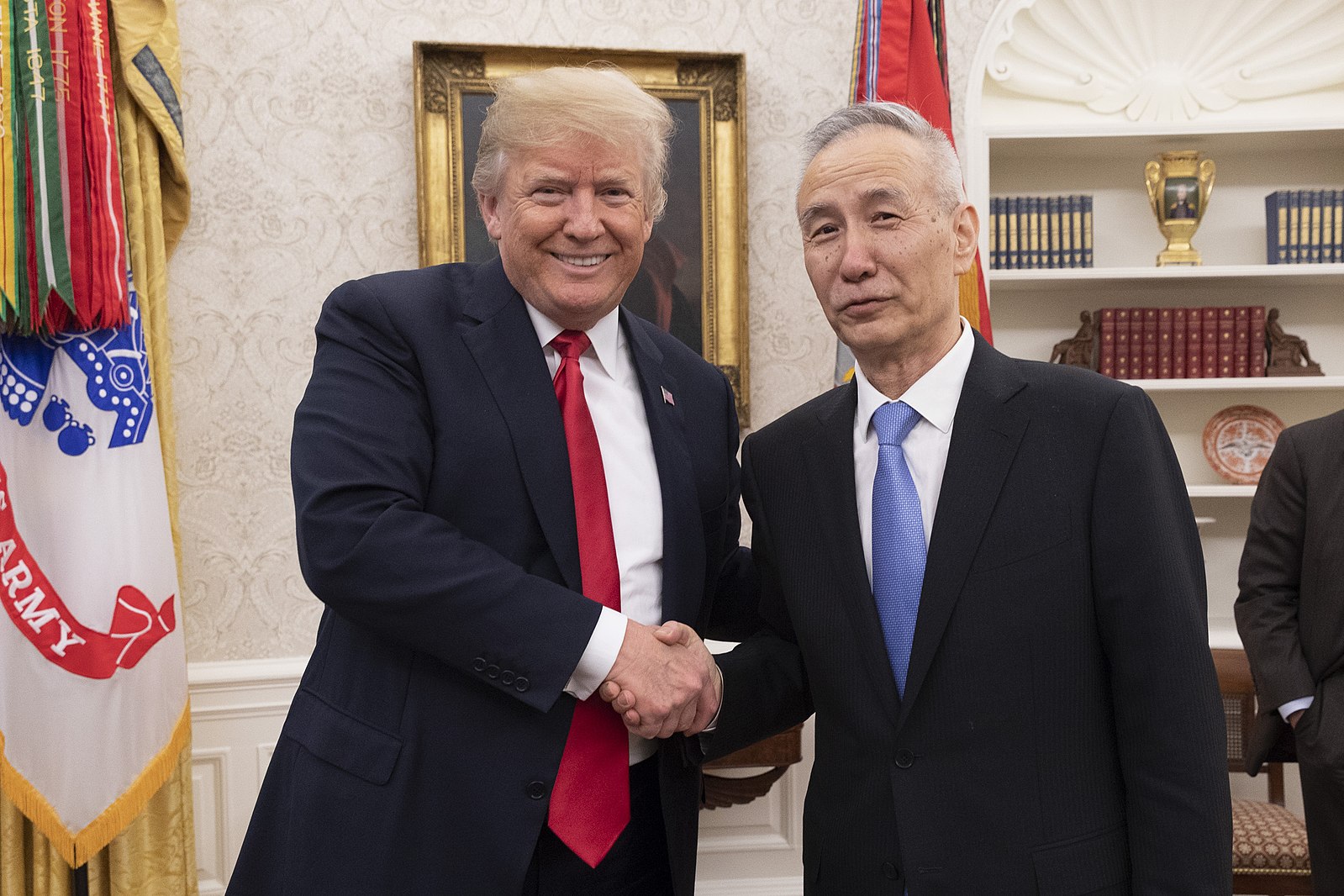

Photo by: Wikimedia Commons