Note: This post is part 1 of a 2 part series. Part 2 will be available on Friday, October 18.

It sounded like a fantasy novel.

In the heyday of furniture manufacturing, she said, a high school student could drop out, walk out of his schoolhouse, down the road by the river to one of the furniture plants and get a job on the line that day. Within a short while, he could eventually buy a car, a house, and support a middle-class lifestyle for the rest of his life.

And if he wanted a little upward mobility, he could quit his plant job, walk down the street, and pick up a job at a competing plant for maybe a little bit more per hour.

This was former Roanoke Times reporter and author Beth Macy setting the scene for her forthcoming book about the Bassett Family – furniture manufacturing lions and the backbone of economic growth in the southern part of Virginia throughout much of the 20th century.[1]

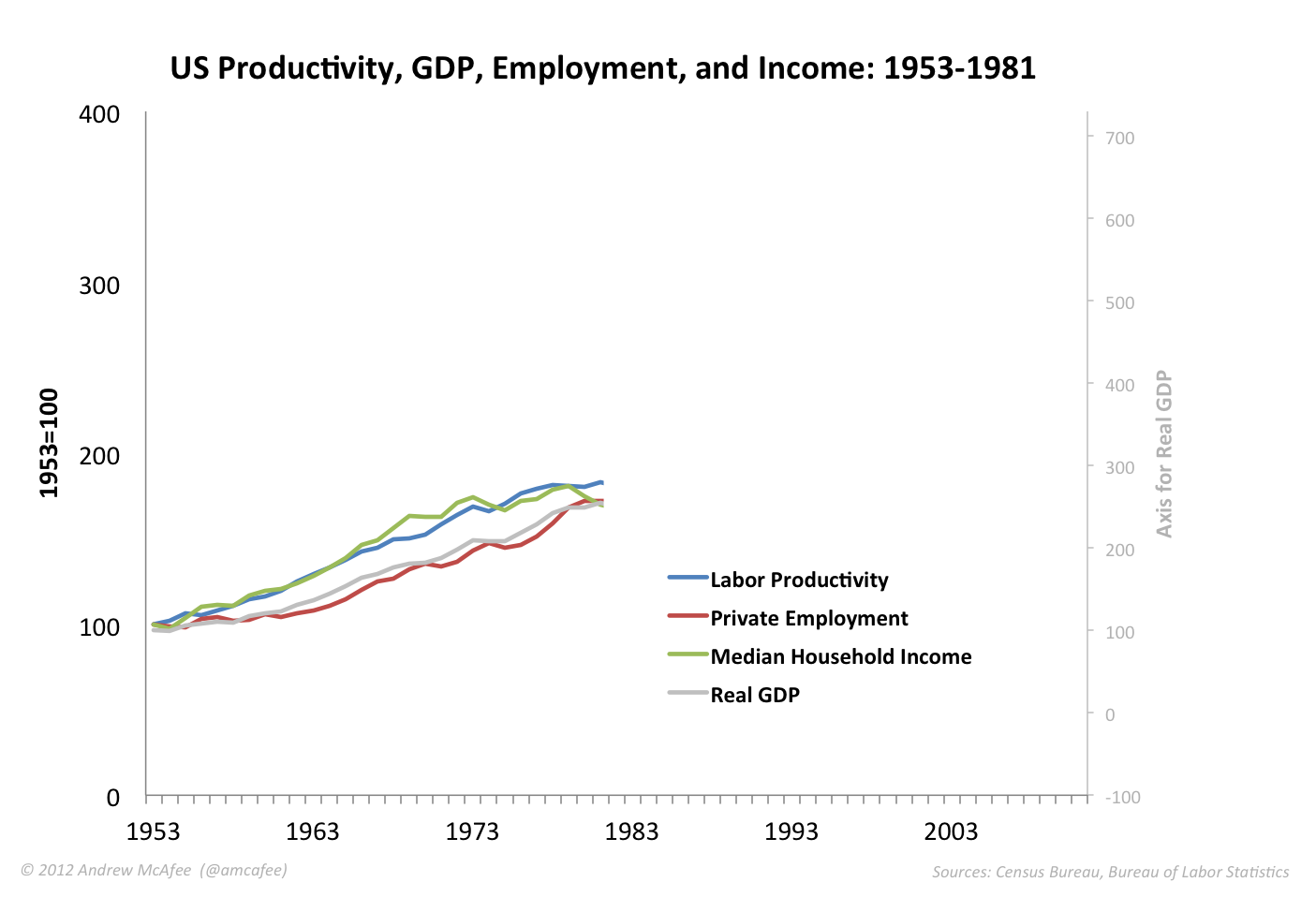

Macy was sharing these sepia-toned stories of middle-class stability with a few Kennedy School students and me in Roanoke, Virginia this past summer. The stories she shared fit the macroeconomic data from that time. As early as 1943, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics began cataloguing data, gross domestic product (GDP) grew in lockstep with median family income. This trend of shared growth continued well into the mid-1970s. For decades, as the country’s overall economic performance grew, the median American family saw similar gains in their income.

Then something went wrong.

As Andrew McAfee, principal research scientist at the Center for Digital Business in the MIT Sloan School of Management, charts, this close relationship between the growth of the country and growth of the middle-class started to crack at the end of the 1970s (marked in the chart below with a green line).

For the first time, median family income failed to grow at the same pace as GDP.

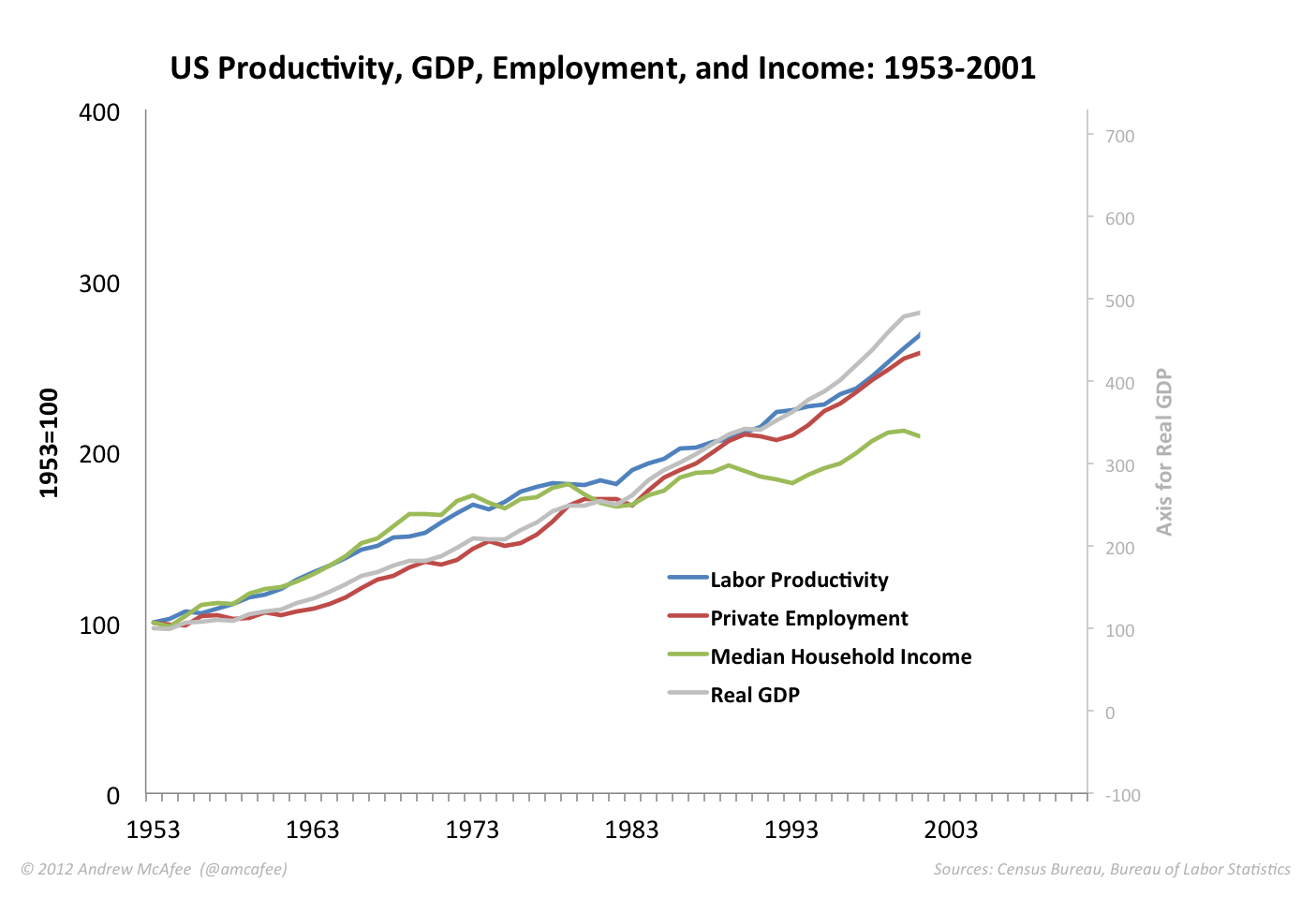

By the early 1990s, it became clear that this trend, called the “Great Decoupling”, was continuing. And private employment soon followed. Not only were families generally making less in relation to the growth of the economy, but job openings were growing at a much slower pace as well.

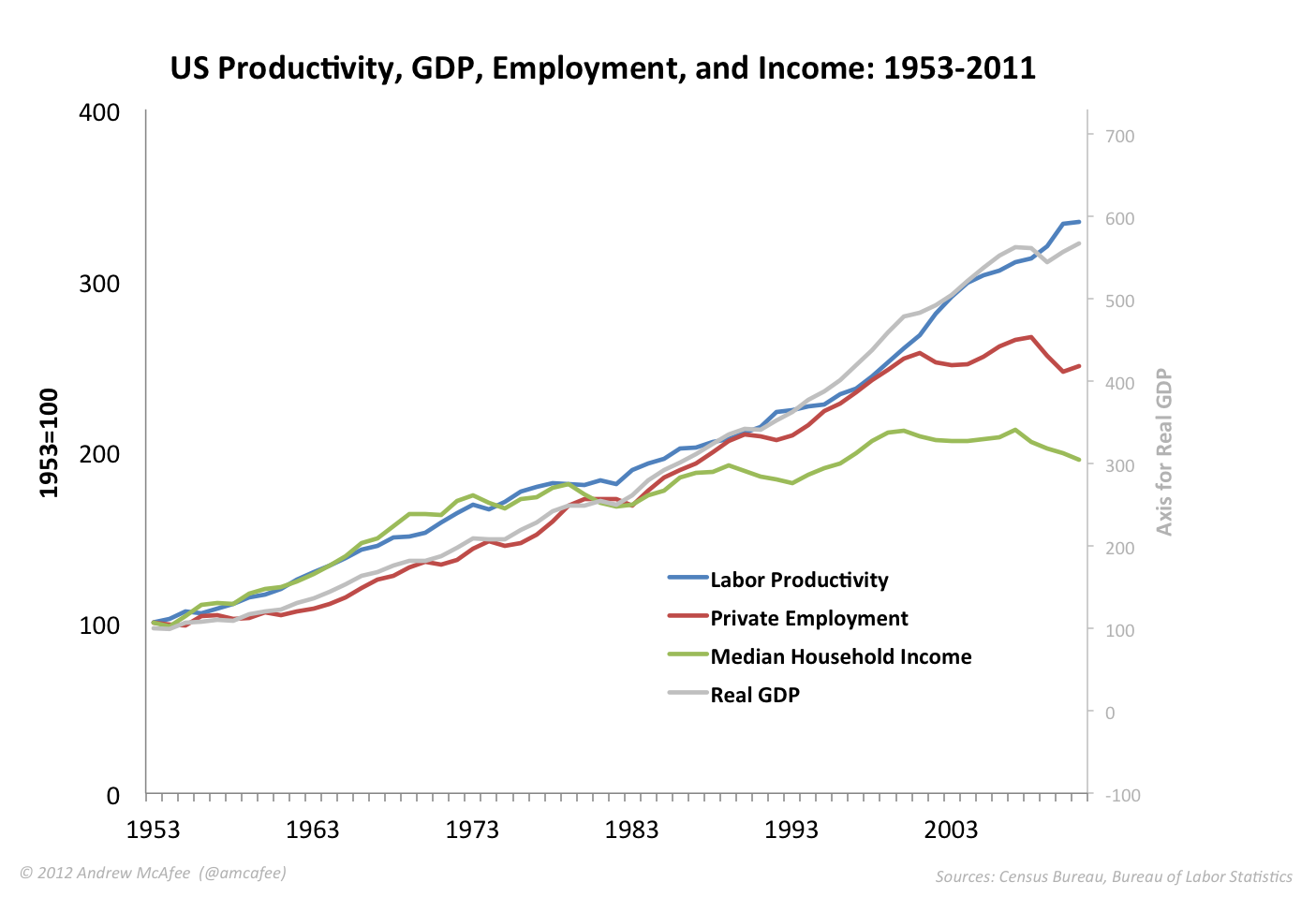

Today, the data shows a permanent and growing gap between the growth of the economy as a whole and the growth of jobs and wages for the median American worker. Today, the growth of the American economy is not a guarantee that middle-class Americans will see any improvement in their income.

The Great Decoupling has changed the idea of what it means to be a worker in America. For many, the pain of this process has been dulled by social programs like unemployment insurance, the Women, Infants, and Children supplemental nutrition program, and Food Stamps. But these are temporary policy solutions for struggling families trapped in what has become a permanent, defining feature of the American economy in the 21st century.

What, then, can we do about this growing chasm in our economy? Short of making major structural changes to our national economy, my next post will look at three ways we as students and citizens can get involved in pushing back against the Great Decoupling.

[1] For more of Macy’s coverage on workers in central Virginia, read her new article “What Globalization Looks Like – In America” in The Ochberg Society magazine.