Mitigating the Sahel Security Conundrum: The Need for a Strategic Paradigm Shift

The Sahel security conundrum (described in this article as an “immunodeficiency security disorder”) is a unique security dilemma facing the region. The Sahel region represents the ‘spinal cord’ of the continent’s geopolitical body, and as such the phenomena of its security conundrum not only poses a real security threat to Africa, but also the spill-over effects have become a global security nuisance, particularly for Europe. The approach to contain this situation that is driven by multiple factors (unstable politics, terrorism, foreign debts, environmental degradation, civil wars, food insecurity, mass displacement, porous borders, illegal migration, and drug trafficking) requires a strategic paradigm shift that goes beyond the current conventional strategies devised by the national, regional, and international actors involved. Instead, a range of fundamental and structural adjustments are needed, including: popular participation as a core issue in redefining good governance, structural reformation of security sectors, qualitative upgrading of humanitarian interventions, and changing and updating school curriculum in humanities—particularly in more vulnerable countries like Sudan and Nigeria—to suit modern education standards.

Introduction

The Sahel security conundrum, a crisis emanating from the old-fashioned political order and risky arrangements of the region, now not only generates a deeper and wider self-destructive momentum, but also is sending far-reaching shockwaves of hazards that severely affect the entire continental security system, as well as its spill-overs affecting the larger globe, especially on Europe. Mitigating the impacts of this immunodeficient security disorder requires, among other remedies, a fundamental and holistic paradigm shift that must include devising a new conceptual frame for systems of “good-governance” that ingrains popular participation as a core issue, adopting structural reformation of the security sector (including army, police, intelligence services, and other security apparatuses), introducing structural adjustment on the concept of “partnership with international community” and reviewing and standardizing of school curriculum particularly in more vulnerable countries like the Sudan and Nigeria in a manner that allow the promotion of the concept of religious tolerance to mitigate the extremist tendencies of radicalism, extremism and terrorism.

The need for such structural paradigm shift is now more important than ever because the geopolitical position of the Sahel—which functions as a spinal cord controlling the region’s nervous system—is sending injury signals that could cause a virtual paralysis of continental security, or even its total collapse.

I. Sahel: The Geopolitics and the Current State of Affairs

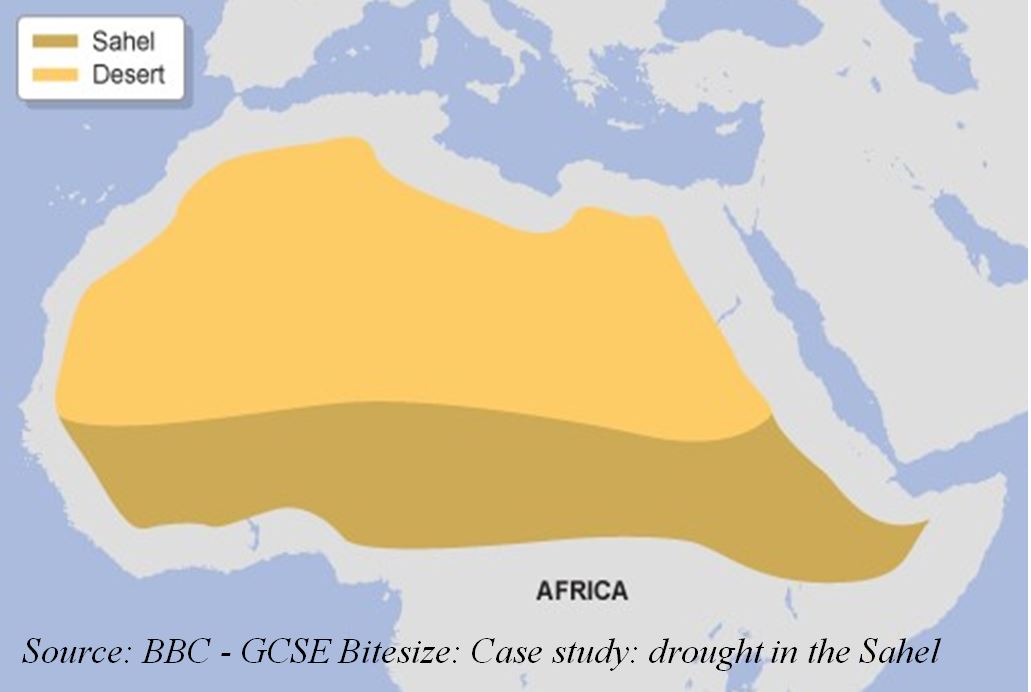

Precariously balancing the African continent in in almost every aspect —from geography, history, culture, environment, population, security and politics—the Sahel region stretches from the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea coast in the East to the Atlantic Ocean in the West Coast. Covering an expanse of more than 7034 km from Mogadishu, Somalia to Dakar, Senegal, the region includes countries such as the collapsed Somalia, the small and resource-scarce Djibouti, drought-prone Ethiopia and its archenemy Eritrea, the Islamist hub and ethnically polarized Sudan, and the newest and highly troubled nation of South Sudan. The Sahel belt further encompasses potentially explosive Chad, drought-stricken Niger, Burkina Faso, war-torn Mali, resource-cursed Nigeria, poor Togo and Benin, religiously tensioned Cote d’Ivoire, little Gambia, and one relatively stable state—Senegal. The rest of the states in the belt are the anti-slavery-campaign-target Mauritania, Liberia, Sierra Leone and the two Guineas (Bissau and Conakry). Serving as home to more than 60 percent of Africa’s population, the Sahel is the origin of most of the Africa’s civil wars.[1]

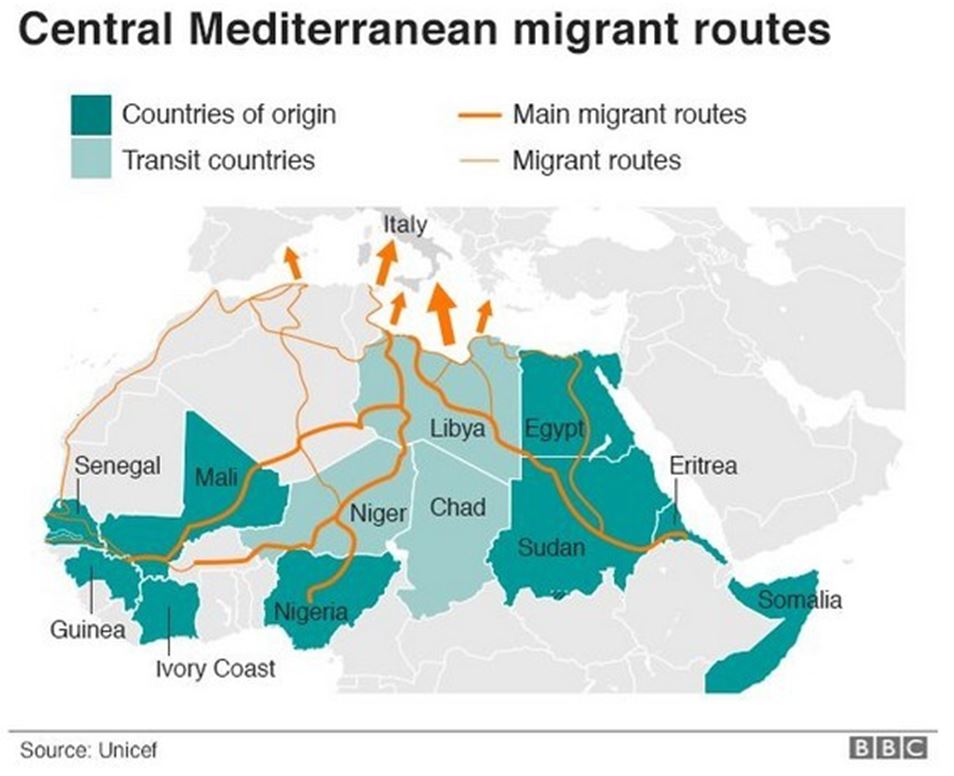

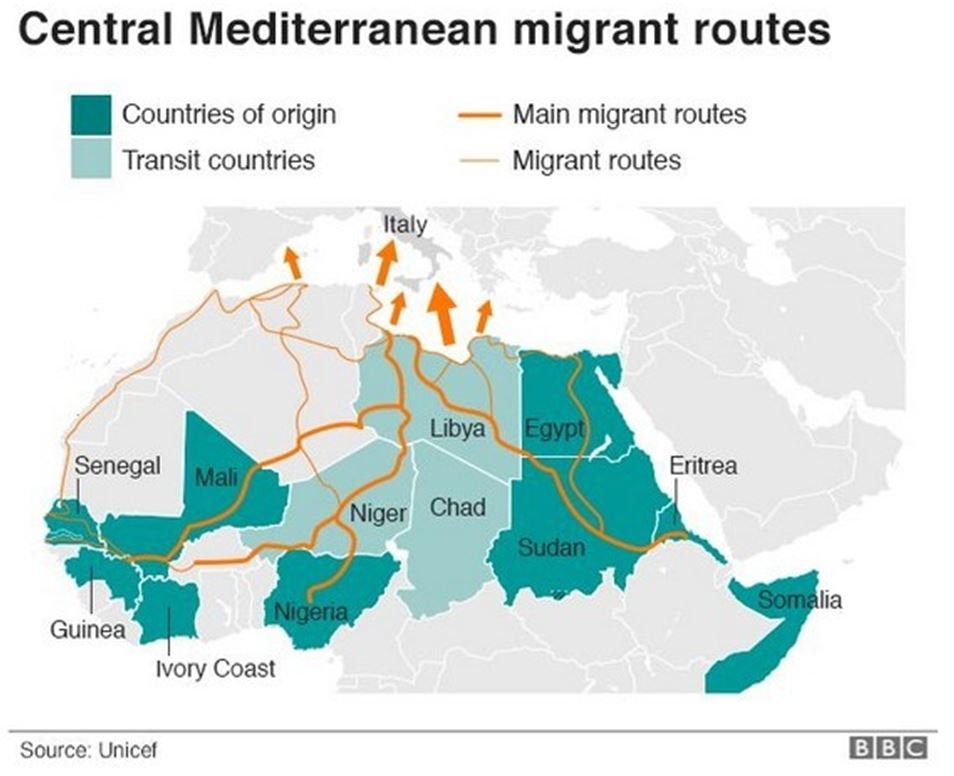

The Sahel’s geographic scope and the unfortunately violent and volatile realities of its component countries have made her the host of the largest international peacekeeping forces. From the environmental perspective, the Sahel belt (boxed-in by the Sahara Desert and tropical Africa), is classified as having cyclically hard-hitting environmental degradation records associated with drought, rapidly encroaching desertification, scarce water, and acute food insecurity. Furthermore, in economic and developmental terms, the World Bank has designated all the Sahel countries, except Nigeria, as “Heavily Indebted Poor Countries” (HIPC). This all around chronic situation is further compounded by the reality that the Sahel region has most of the continent’s refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). Moreover, the region has become a fertile breading ground for the seemingly ever-expanding radical Islamist militants, as well as a conducive ground for the proliferation of small arms and international drug trafficking. The Sahel region is also the sole major exporter and traditional exit corridor for the largest percent of Africa’s illegal migrants to Europe.

This multi-faceted security crisis facing the Sahel region has already spilled past its boundaries and been felt by the region’s neighbors, and often with terrorism-related events, especially in Kenya, Uganda, the Central African Republic (CAR), Cameroun and Ghana. It is this intricate mosaic formula that constitutes the metabolism of the Sahel security nexus.

II. Sahel Security: Actors’ Perspectives and Experts’ Views

The African Union’s (AU) strategic position on Sahel security is spelled out in its document entitled “The AU Strategy For The Sahel Region,” which provides that:

The present Strategy of the African Union for the Sahel Region is centered on three main pillars: (i) governance; (ii) security; and (iii) development. These three areas, especially the first two, are issues on which the AU has a clear comparative advantage, as per its continental mandate, its experience in the subject matters and its familiarity with the issues at hand. [i]

However, the AU’s position, at least as reflected in this document, deserves careful examination and comment. While the AU strategy document expresses the continent’s visible concerns over the unique challenges of Sahel security, it also reveals and recognizes, in a contradictory manner, the AU’s profound limitations and its inability to face the challenges posed by the Sahel. This is quite clear from the subsequent provision of the strategy document:

It should be recognized that issues of the Sahel zone do not concern Africa only, for some of the threats identified, as the insecurity and terrorism, go beyond the region and the continent. It is in this context that the AU welcomes the interest in the region and the commitment of the United Nations, the European Union (EU), and other international actors.[ii]

The United Nations (UN), like the AU, has expressed clear concerns over the Sahel region. Endorsed by the Security Council in June 2013, the UN adopted what is termed as “Integrated Strategy for the Sahel” [S/2013/354], as a new instrument for “conflict prevention.” The UN strategy “prioritizes life-saving activities in the areas of political, security and humanitarian affairs that meet immediate needs, while building the resilience of people and communities as part of a long-term development agenda.”

Echoing the same spirit, the UN Special Envoy for the Sahel Mr. Romano Prodi once warned the international community when he said, “do not forget the Sahel, or you will have more Malis if you do.” In addition to the above engagements, and apart from the multidimensional peacekeeping forces deployed throughout the Sahel hot spots,[iii] the UN also supported a new anti-terrorism force that proposed by five Sahel nations—Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Niger. The force, which is anticipated to deploy 5,000 security personnel by March 2018, will cooperate with the ongoing French deployment in the region and will be funded by the five participating countries, the European Union, and the United States.

With these generous responses, it remains one’s considered view that, irrespective of how innovative or responsive, these initiatives and instruments demonstrate one overriding reality: the continued fragility of the Sahel region.

One cannot but wonder whether at any single given point in history a single region has combined such hydra-headed problems like the Sahel is.

III. Experts’ Views and Perspectives on the Issue

Experts’ views on how to contain and mitigate the Sahel security conundrum is critical of the relatively conventional approaches pursued by the AU, the UN, and other global actors.

Mr. Chester Crocker, the high flying former US Assistant Secretary for African Affairs, and Ellen Laipson, in a co-authored piece for the New York Times, described the Sahel region as but “the latest front in a long war” and asserted that, “the turmoil in the Sahel is shaping up to be a long-playing conflict that will end well only with the help of African regional organizations, Western nations, nongovernmental groups, and the United Nations.”[iv] The authors further expressed that the small and then-recent victory in Mali was “just the beginning of what will likely be a very long struggle for control of the Sahel,”—or what they refer to as “the trans-Saharan badlands that stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.”[v] Crocker and Ellen’s views confirm two singularly important points: (1) that the Sahel’s problems are beyond African capacity, and (2) that the war in Mali only represents the tip of the iceberg of Sahel’s long-term security dilemma.

Looking to other experts, Martin Michelot and Martin Quencez of the Paris office of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, while analyzing the Sahel security in their paper on “Why the Sahel Is Crucial to Europe’s Neighborhood — and Its Security Strategy,” noted that:

Despite receiving official backing from allies on both sides of the Atlantic, the French military intervention in Mali also revealed the reluctance of countries to share the burden for providing security in the Sahel. The problem stems mostly from the divergence of perceptions within Europe on the relevance of the Sahel to its immediate security concerns.[vi]

In the authors’ view, “[t]he first step should therefore be to redefine the scope of Europe’s neighborhood strategy in order to include the Sahel area as a whole.”[vii]

Ms. Idayat Hassan, of the Centre For Democracy and Development in Nigeria, more recently argued that “the question to be raised is, whether the EU Sahel Strategy indeed reacts to the concerns and internal dynamics of the region in enough ways to stem insecurity?” Her answer to that question is a resounding “NO.” As she explains, “as military operations and increased spending alone won’t root out terrorism or curb illegal migration, the EU and other entities involved in development will have to focus more on addressing the root causes.” She went on to further explain, “all of these goals are already espoused in the EU strategy on the Sahel, but more political will and prioritization will have to be applied for long-term stability.”[viii]

Furthermore, Luca Raineri and Alessandro Rossi of the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), in their paper “The Security-Migration-Development Nexus Revised: A Reality Check” argued that:

Policymakers and experts have increasingly emphasized the nexus between migration, security and development in the Sahel. Contrary to conventional wisdom, higher levels of economic and human development do not result automatically in a reduction of migratory flows. Sometimes the opposite is the case. Similarly, it would be wise to nuance the view that armed conflicts automatically provoke huge migration flows. Policy frameworks sponsored and designed by foreign actors in the region, such as the European Union and the United States, seem to understand the need for a multi-layered approach but are sometimes stretched to meet inconsistent political demands. There is an urgent need for coherent, more evidence-based and less fear-based policy-making.”[ix]

Dr. Jerome Tubiana, a researcher and expert in armed non-state actors affairs in the Sahel region told this author that:

“The two of the major areas that needs an structural paradigm adjustment are how to accommodate into power structures the Sahel’s pastoralist cross-border communities (particularly the Tuareg, Tubu, Zaghawa, and Arabs) and how to accommodate the unemployed disgruntled youth into a gainful opportunities. As these always undermine international security arrangements, such initiatives will reduce the random border-crossing activities of these pastoralists and absorbs the disgruntlement of these youth who could easily joint terrorist groups.”[x]

Mr. Rasheed Saeed, a Paris-based Sudanese journalist and editor with French defense weekly review publication (TTU), and who also covered Sahel regional affairs for decades, also gave an interview to this author and summarized his assessment as:

A combination of socio-political factors are determining region’s instability including structural defects in power sharing arrangements, fast track changes, presences and crisscrossing of foreign militants such as Algaeda elements, Daesh affiliates and Boko-Haram fighter, together with the apparently contradictive policy approaches pursued by the super power actors, irreconcilable priorities of the region’s governments and fast fragmentation of local communities are all compounded to fuel and inflame the situation and pushed to the evolving anarchy.[xi]

Commenting on the recent shock created by the slave-auctioning reports from Libya, Dr. Amjad Fareed, a researcher and analyst on the Horn of Africa’s political affairs, holds that:

The tightness of border control policies and the blockade of asylum routes is the main cause for the return of slave trade to the modern age by this scale. In reality, most of the refugees and/or migrants as the EU now want their name to be, are not being kidnapped against their will. They resort to smugglers as their only choice to find their way out of conditions of “well-founded fear of persecution” or in which their physical, legal and material safety and their dignity and basic rights cannot be made available. The international law gives them the right to seek refuge, but in the absence of safe pathways of obtaining this right, resorting to smugglers becomes the only choice. While refugees are right’s agents, smugglers are not rights’ defenders, they are doing this as for-profit business and they can easily turn sides as has been proven by the Italian measures. Putting a price tag on stopping refugees whether by aid packages to failed regimes that are part of the root-causes of the asylum phenomena or by direct payments to militias is the first step of the commodification of refugees and taking away their humane identity. This does turn them to goods in the eyes of illegal gangs. Then human trafficking finds its conducive environment to grow with the goods made available and free of charge or with a little price. The same smugglers are turned to traffickers by the currently implemented security measures for double profit. The other ugly fact about the outrageous western reaction to the slave trade crisis is about the attempts to use it to force asylum seekers/refugees back to the situations they were trying to flee in the first place without working on solving the roots of their problems or guaranteeing their safety. This would be the most unethical, unprincipled and wicked European act, since Europe decided that it “discovered” Africa).[xii]

What is particularly important here is the surfacing of the slavery and slave trading issue, which is by all means a testimony of the vulnerability and complexity of the Sahel regional affairs and challenges. The extent of this vulnerability and complexity further speaks to the existence of their root causes that have not been eliminated and hence the possibilities of continued reemergence of such issues.

IV. The Needed New Thinking, New Approaches, New Paradigms, and New Security Order

To diagnose the underlying causes for the Sahel’s security immunodeficiency disorder, it is imperative to subject the region’s entire political ecosystem to a critical and careful anatomical analysis, from every dimension. A comprehensive and dynamic approach that helps to determine both the congenital and/or secondary nature of the threats is important as that would help to develop an alternative paradigm system.

Picking up issue by issue, it is this author’s view that the conglomeration of factors propelling immunodeficiency disorder in Sahel security can generally be grouped under four major categories of history, geography, religion, and identity, as well as the very critical and broader issue of “governance.”

In terms of history, it is obvious that Sahel’s socio-political analysts have drastically overlooked and simplified the historical aspects of the matter. This lack of historical sense has prevented the political actors to accurately appreciating and identifying the historical background of the prevailing predicament.

Sahel, the historical birth region and a deposit-belt for the ancient indigenous Sudanic civilizations was at a certain point forced to twist its fate and go through a painful political face-lift process. In the medieval centuries, the region was forced to become a growing field for a number of quasi-Islamic kingdoms, empires, and sultanates, such as that of Bornu, Mali, Songhai in the West, Wadai, Darfur in the Centre, and Sinar in the East. This involuntary evolution, which resembled a kind of clash of civilizations, has affected and alienated the region’s natural individuation process and has set a state of confusion. This congenitally caused state of disorder has become a permanent characteristic of the region today. While this important background explains the emergence of the ongoing mushrooming of Islamic militants, the conviction of these militants and their aspirations is to repeat history. This state of affairs has further been reinforced by another similar experience that is more recent in time and more anti-western in stance. It is the Mahdist movement in the Sudan and the Danfodio Khalifite in West Africa. This accumulated heritage constitutes a strong background that explains the political root causes for the current Islamic extremist phenomena. These extremists also believe that they are, in part, battling to accomplish a historical duty of an incomplete mission.

On the other hand, the poorly arranged and minority elite-based patriarch regimes in the Sahel region have neither the necessary comprehension of the historical sense nor the requisite political will or stamina to effectively contain this major security threat.

In terms of geopolitics, the Sahel is an incredibly strategically important region that can severely impact both the North and South of Africa.

Additionally, the pertinent issue of governance is in dire needs for structural reformation at both strategy, actors and mechanisms.

As these naturally corrupt minority elites dominate and abuse power in, the major missing link is the absence of good governance that should embrace fundamental elements of popular, gender, and marginalized participation. This is the magical catalyzing factor that can help to redefine and re-equate the much-needed new paradigm shift.

Another area that requires a major paradigm shift is the security sector. The shift needed here requires a sector that is national in character and proportional in representation. But the most salient point in this scheme of arrangements that need for a major policy shift is redefining the ambiguous and loosely defined concept of international partnership. The necessary redefinition would embrace the idea of international intervention, particularly in the humanitarian aspect. This would serve multiple purposes, including stopping humanitarian disasters and addressing mutual security arrangements. The rationale behind such a redefinition is propelled by the failure caused by corrupt minority elites who have not only irredeemably failed to effect any meaningful structural changes in any of the Sahel respective experiences, but also who have played a role in sabotaging and obstructing any given popular-based attempt for structural transformation process in the Sahel.

V. Conclusion

With the above anatomical diagnosis of Sahel security conundrum, it is this writer’s considered view that a rational policy shift for the region should focus on a range of issues. First, there should be a focus on how to clearly and creatively define the needed New Security Order—a synchronized vigilance system that manages the trinity of freedoms, economic welfare, and safety of the citizens. Second, focus is needed on how to clearly identify priority areas for adjustment, of which the issues of humanitarian, employment, curriculum, freedoms and rule of law are of paramount importance. There, there must be an identification of the new actors that are capable and energetic to carry out such policies, such as civil society, women, youth, and marginalized groups. Fourth, new mechanisms necessary for this scheme—such as effective and representative parliament, vibrant media and press, independent judiciary, viable civil society, and a mandated, strong, and independent international oversight body, amongst others—must be established. Finally, there must be a scheduled time frame involved for these shifts, including prioritized short, medium, and strategic timeframes for reform.

[1] Most notably, the Sahel region has included the civil wars in Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Chad, Mali, Nigeria, Liberia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Sierra Leone.

[i] African Union, The African Union Strategy for the Sahel Region, para. 2 (Aug. 11, 2014), available at http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/auc-psc-449.au-strategu-for-sahel-region-11-august-2014.pdf.

[ii] African Union, The African Union Strategy for the Sahel Region, para. 16 (Aug. 11, 2014).

[iii] Including the United Nations/African Union in Darfur (UNAMID), the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), the United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS), and the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA).

[iv] Chester A. Crocker & Ellen Laipson, The Latest Front in a Long War, The New York Times (Mar. 7, 2013), available at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/08/opinion/global/the-sahel-is-the-latest-front-in-a-long-war.html.

[v] Chester A. Crocker & Ellen Laipson, The Latest Front in a Long War, The New York Times (Mar. 7, 2013).

[vi] Martin Michelot & Martin Quencez, Why the Sahel is Crucial to Europe’s Neighborhood — and Its Security Strategy, The German Marshall Fund of the United States (July 11, 2013), available at http://www.gmfus.org/blog/2013/07/11/why-sahel-crucial-europe%E2%80%99s-neighborhood-%E2%80%94-and-its-security-strategy.

[vii] Martin Michelot & Martin Quencez, Why the Sahel is Crucial to Europe’s Neighborhood — and Its Security Strategy, The German Marshall Fund of the United States (July 11, 2013).

[viii] Idayat Hassan, The EU’s Strategy for Sahel Security, The Cipher Brief (Apr. 9, 2017), available at https://www.thecipherbrief.com/the-eus-strategy-for-sahel-security-2.

[ix] Luca Raineri & Alessandro Rossi, The Security-Migration-Development Nexus Revised: A Reality Check, Institute Affari Internazionali (2017), available at http://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/iaiwp1726.pdf.

[x] Personal interview with author.

[xi] Personal interview with author.

[xii] Amjad Fareed, The EU and Refugees, http:sudanseen.blogspot.com.