What happens to your recycling when the noisy, traffic-inducing truck picks it up each week? If you are like me, you picture it arriving at a nearby plant and then magically getting reincarnated. The reality is more complicated. First, our recycling is cleaned, sorted, and packaged into bales at local Materials Recovery Facilities (MRFs). Then, the bales are sold to facilities that process the waste into new materials. At least one-third of the bales are exported overseas, the majority of which are sold to China.

Since 2001, China has been the world’s largest importer of recycled waste. That’s because it’s cheaper for advanced economies like the US, to ship recycling to China in containers that previously held Chinese exports, than to send recycling to domestic plants. China then transforms the waste into raw materials to be exported back to the U.S., and so goes the cycle.

That was, until last year, when China implemented its National Sword Policy limiting imports of foreign recyclables. US recycled plastics exported to China have since dropped by 92%. Now, hundreds of thousands of bales of recyclable materials remain stuck at processing facilities across the U.S. with nowhere to go.

One motivating force for National Sword is that much of American recycling is too contaminated to be recycled. The majority of municipalities in the U.S. follow single-stream recycling methods, permitting residents to throw different types of recyclable products in one bin. While this eases the burden of waste disposal, residents are less mindful of what they can and cannot recycle. As a result, a mélange of materials, including those that are either unintended for mainstream recycling (like electronics), dirty (like greasy pizza boxes), or pure trash, mix into a single bin. As much as 30-50% of bales of recyclable waste shipped overseas are contaminated.

Due to the China’s new limits on imports, American recycling programs have few alternative destinations for their processed waste. The materials are now rerouted to other markets in southeast Asia. However, a growing number of countries are announcing their own restrictions on imports. It is thus becoming costlier for companies to collect waste because it is harder to sell.

Since recycling collectors are unable to dispose of materials at the rate they require, they resort to either paying companies to take the materials, or dumping them in a landfill. Landfills are breeding grounds for bacteria that attract vermin, spread disease, lower soil quality, and contribute to respiratory illness. The decaying waste releases potent greenhouse gases. Landfills affect the natural landscape, smell terrible, and undermine the credibility of recycling programs.

In response to this crisis, policymakers should consider the following three recommendations:

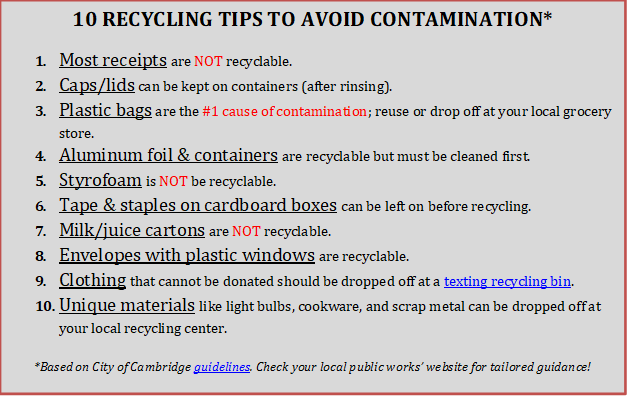

1. Enforce clean recycling. While MRFs attempt to account for human error, the effectiveness of the technology is limited. We therefore need to invest in information campaigns to deter recycling contamination. Recycling bins, at home or in public, rarely come with user-friendly manuals. Because recycling is decentralized in the US, it should be the responsibility of each municipality to disperse this information more broadly. D.C. Public Works recently launched a marketing campaign and witnessed an 8% reduction in contamination.

2. Fortify domestic capacity. In addition to reducing dirty recycling streams, we need greater investment in recycling infrastructure. Because foreign markets are no longer willing to recycle our waste, domestic processing plants are becoming so inundated that they are turning materials away. Public entities need to collaborate with private companies to bring recycling technology to scale and build new full-service facilities across the US. While these can cost millions, recycling companies have already made large investments in new plants. The result: an increase in domestically-processed materials that are sold to foreign manufacturers, thereby generating revenue and improving America’s competitive advantage.

3. Revolutionize product packaging. The first two steps alone are insufficient to address our crisis. We need to reform the way we consume, which requires incentivizing producers to update their packaging. Many products sold to consumers are single-use, packaged with non-recyclable materials (think: toothpaste, chip bags, and single-serving yogurt). Moreover, with the rise of e-commerce giants like Amazon, stockpiles of cardboard boxes exacerbate the crisis. Producers have the technology to redesign packaging in a sustainable and cost-effective way. They therefore must be held responsible for the waste they introduce to the market. Some companies have recently began testing reusable containers that can be refilled. Others are shipping material in packaging that can be reused by the consumer or producer.

These recommendations target our unsustainable culture of overconsumption and negligence, and our inability to regulate the waste we produce. As the average American’s means to dispose of their waste simplifies, so too should the nation’s ability to manage it. We must ask ourselves: do we revolutionize the way we Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, or do we continue to dig massive holes in the earth, hoping that our million-ton problem disappears?

Edited by Hilary Gelfond

Photo by Alfonso Navarro