It is hard to overlook how unequitable the roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccines has been. The number of doses administered in the wealthier world has far outpaced the vaccination rates in the poorer nations. While people in the wealthy nations are gearing up for their summer vacation – all fully vaccinated, the poor regions of the world are experiencing catastrophic second or even third waves. Experts predict that it could take until 2024 for them to catch up.

Amidst this, the debate over intellectual property rights (IPR) has resurfaced at the World Trade Organization (WTO) yet again, with the developing countries calling for a waiver of patents on COVID vaccines. They believe IPR to be a prime reason for vaccine inequity. But waiving off IPR on vaccines may not do the trick, not at least in the short run, as is needed. It could take months to negotiate the IPR waiver; months to carve out the specific rules; and even more time to translate this into actual production – and still prove inadequate in the absence of technology transfer. With the clock ticking fast, alternatives to deal with vaccine shortage need to be prioritized over IPR suspension negotiations.

The COVID vaccine production recipes are protected by patents held by the vaccine developers. Any country wanting the recipe must buy these patents which tend to be very expensive.[1] Waiving off patents rights they argue, will help scale up production by making the recipe available openly. However, vaccine manufacturing requires more than just the recipe. Know-how and technology for production need to be transferred from the vaccine developers to potential manufacturers, something that IPR waiver will not guarantee.

The COVID-19 vaccine market consists of numerous companies utilizing different technologies, the mRNA technology being a novel one. Unlike ordinary drugs which are “simple chemical compounds” and can be recreated in a lab through a process called “reverse-engineering”, vaccines are biological products requiring a complex biological manufacturing process. Even with the know-how, it could take years to build capacity for production from scratch and to train personnel in mRNA technology. Moderna, for instance, has pledged to not enforce IPR on its vaccine but has not shared any details about the manufacturing or design process.

Another issue pertains to quality assurance. Inspection and testing at each step of the process to ensure safety of each batch is critical. Any glitch in the regard even by a single manufacturer could have serious consequences and ultimately thwart the entire vaccination drive. Oversight by the developers will be crucial in the manufacturing process.

Finally, it is not just about the “global” IP rules. Many bilateral trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) have embedded provisions that can prevent national drug regulatory authorities from registering and allowing the sale of generics if the vaccine is still patented. Such rules could prevent vaccine manufacturing without patents even if the decision to waive off IPR was taken at the WTO.

Alternatives to IP-related measures will achieve quicker results.

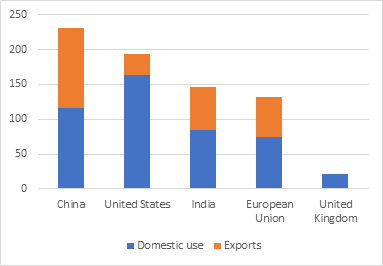

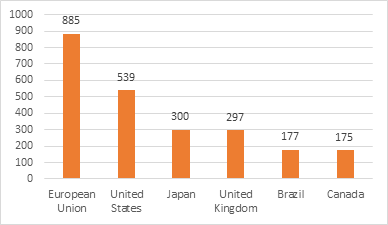

First and foremost, export restrictions must be avoided. At all costs. So far, the European Union, the United States and India have all restricted exports of vaccines. Only six countries are likely to account for nearly 90% of global surplus of vaccines by the end of the year which is estimated to be nearly 2.6 billion doses. Increasing exports will accomplish more, and quickly so, than an IPR waiver. The United States has already committed to sharing 500 million vaccine doses with the rest of the world. Other countries must follow suit.

Figure 1: Vaccine exports, April 2021 (USD million)

Source: Airfinity

Figure 2: Estimated vaccine surplus by December 2021 (million doses)

Source: Global Trade Alert

Not just vaccines, countries must steer clear of imposing any export restrictions on raw materials and equipment needed to produce, distribute, or administer vaccines. Shortage of any one input – cold-boxes, antibiotics, preservatives, etc. could disrupt the entire supply chain. For instance, the United States’ ban on export of key raw materials needed for vaccine production slowed down production in India which had ripple effects on the entire developing world depending on India.

Equally important is to release the stock of vaccines awaiting regulatory approval in some countries despite being approved in other countries with similar regulatory frameworks. For instance, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine has not been approved in the United States and Switzerland who are holding on to over tens of million doses of the vaccine for several months. The vaccine has however, already been approved and is being successfully administered in the European Union and the United Kingdom. While this is not unusual given that regulatory requirements can vary across countries, the intent to hold on to the stocks is questionable. Why waste time? Why not export these to the developing countries through the COVAX initiative instead?

Minimizing tariffs and non-tariff measures (NTMs) on vaccines and related intermediate inputs will facilitate vaccine trade. Average world tariffs on vaccine ingredients such as preservatives, adjuvants, antibiotics range between 2.6% and 9.4%. Tariffs on other materials to administer vaccines, such as syringes and needles, packaging or distribution materials can go up to 12.7%. A number of standards and technical regulations, mainly in the form of technical barriers to trade (TBT), sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS), price-control measures, and import licensing measures, also apply to pharmaceutical products and organic chemicals. Governments should make efforts to minimize these. Emergency use authorization, fast-track approvals of imports, elimination of value-added taxes; are some of the steps already being undertaken by many countries.

WTO Director General, Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s “third-way” approach based on voluntary licensing deals is a solid one. It will allow vaccine developers to transfer vaccine know-how and technology to other manufacturers, say in developing countries without having to waive off the IPR. In return, they could be paid a royalty based on the vaccine sales. The agreement between Oxford AstraZeneca and the Serum Institute of India (SII) is one such example. Experts from the licensing firms can travel to the facilities of the licensee and oversee operations at least in the initial stages and ensure that quality is not being compromised.

Another way to fill the gaps would be to set up technology transfer hubs in countries with high manufacturing capacity like India, South Africa, Brazil, and other Latin American countries. In these hubs, vaccine developers can share know-how and expertise on vaccine design and manufacturing. Promoting expansion of production facilities located in high-income countries into the Global South will be useful. It is time for the international community to think past this “ego battle” that the IPR debate has always been and collaborate instead on what matters most. No one is safe until everyone is safe. Economically as well, the RAND corporation estimates that vaccine nationalism could cost the global economy up to $1.2 trillion a year in GDP terms. It is in everyone’s interest to scale up production and keep vaccines moving across the globe. IPR waiver will not help resolve current shortages

[1] The WTO Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (The TRIPS Agreement) grants patent owners a protection of 20 years from the date of filing the patent application.

Divya Prabhakar is a trade policy analyst working with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Geneva, Switzerland. She works with the program on non-tariff measures (NTMs) and has in the past managed technical cooperation projects in Kenya and in Myanmar. She holds a Masters’ degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. During her time at Fletcher, she also took courses on trade policy and intellectual property rights at Harvard, both of which are her key international policy interests. Prior to this, she worked as a government strategy consultant at PricewaterhouseCoopers, India where she supported India’s foreign investment promotion agency.

This piece represents her personal view on the subject.

Edited by Khadija Saleh

Image credit: Ivan Diaz