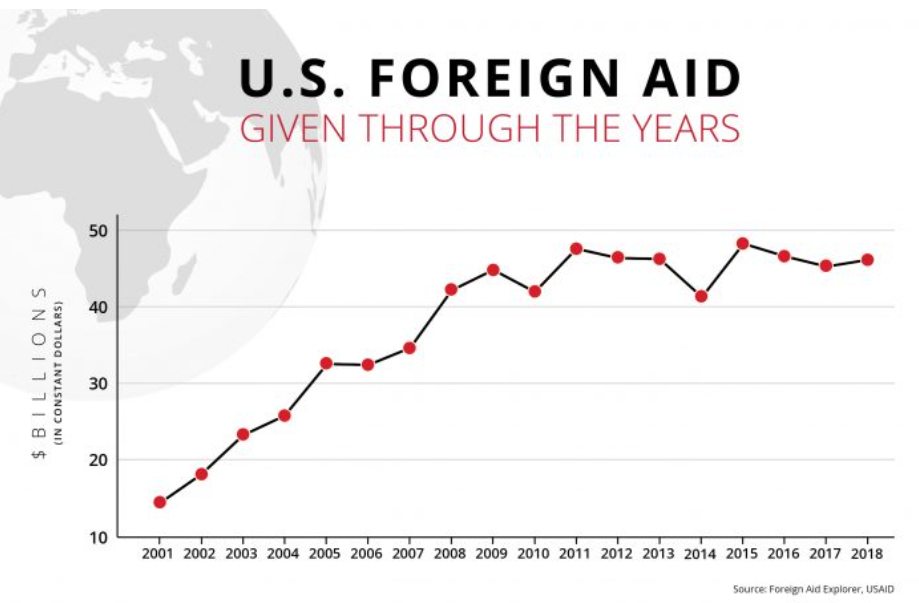

In the last couple of decades, the global percentage of people living in extreme poverty has fallen, reaching 9.2 percent in 2017, compared to 10.1 percent in 2015. However, a closer look reveals a bleak picture. Despite over $1 trillion in aid being funneled to the African continent in the past sixty years, the biggest aid recipients have actually displayed negative annual growth rates. The “Big Push” theory, which stipulates that large investments of aid from wealthy countries can end global poverty, has been challenged by economists based on such evidence, while U.S. foreign aid spending has continued to rise (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: U.S. Foreign Aid Given Through the Years

The foreign aid issue is especially relevant during the pandemic. Multilateral institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have mired developing countries deeper and deeper in debt, which they refused to cancel in the wake of the devastating economic impacts of Covid-19. As the world’s poorest and most marginalized communities have been hit hard by the pandemic, being forced to work in environments that expose them to the virus and often lacking access to medical treatment, we must revisit the question of alternatives to development aid. Amid the crisis of the pandemic, mutual aid, which has been utilized as a political survival tactic throughout history, has re-emerged as an alternative to institutional aid. How can this concept be applied to the development context?

Prior to exploring this alternative, it is important to ground development aid in its historical context. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the U.S. and British governments provided food aid and other forms of international assistance to poorer countries, many of which were colonies at the time. Following the Second World War, the Marshall Plan and the establishment of the World Bank and IMF resulted in a massive influx of aid to the global South. Current-day aid projects cannot be separated from these imperial origins.

In Encountering Development, Arturo Escobar expounds on this in a resounding anthropological critique of development. The discursive construction of the global South as “underdeveloped,” Escobar argues, occurred during the postwar period as a direct continuation of orientalism. This carried heavy ideological implications, as neoliberal development practices were presented as “market-friendly” solutions to the problems of countries which, in fact, required intervention, management, and control. Specifically, Escobar writes that these international economic institutions “provided guidelines to strengthen the private sector, expand domestic and foreign markets, and revitalize international trade under the aegis of multinational corporations.”

In Imagining a Post-Development Era, Escobar describes the impasse of developmentalist discourse: on one hand, it is seemingly impossible to fully transcend its linkages with a violent, imperialist past, and on the other, the discourse is at risk of domination by privileged intellectualization, prioritizing scholarly critiques at the expense of actually impactful action. What, then, is the alternative?

Drawing on the work of scholars in the global South, Escobar argues that we must search for “alternatives to development” rather than development alternatives—rejecting the paradigm wholesale via localized, grassroots movements that are already underway: “these authors see new spaces opening up in the vacuum left by the colonizing mechanisms of development.” Charity is not a sufficient alternative. Charities and nonprofits sustain themselves through the perpetuation of the problem they aim to fix, and do little to level the power dynamic between donor and recipient. Furthermore, a number of charitable projects have been either ineffective or caused unintended harm. One development program in Lesotho inadvertently drove local farmers out of business, and a medical intervention in Egypt actually contributed to increased rates of hepatitis C. This necessitates a structure of social relations operating external to the state, mediated through grassroots social movements.

How can such movements improve the lives of everyday people given that such a vacuum does not currently exist? In what concrete ways can everyday Americans stand in solidarity with popular struggles in the global South beyond charitable donations, which often further re-entrenches a cycle of dependency?

A result of the power differential between aid agencies and aid recipients, and even well-meaning charitable donors and aid recipients, is a profound information asymmetry whereby the donor can dictate exactly what the recipient needs. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) selects the types of food that go into aid packages, and is often also the arbiter of who is deserving of that aid. While the latter question of dessert contains thorny ethical implications, a foundational problem is simply that outsiders may actually have no idea what people want. In a striking example, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo’s Poor Economics describes a poor Moroccan man who declared to them, “Oh, but television is more important than food!” This may seem counterintuitive under conventional economic assumptions – why would someone choose to purchase a TV while going hungry? On further examination this is a perfectly rational choice – things that decrease monotony and increase the pleasure of daily life are a priority for people in poverty, just like for everybody else.

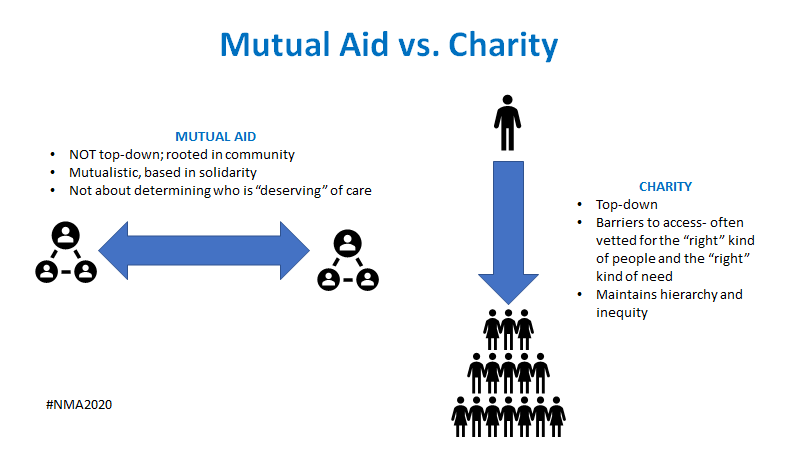

This insight is critical because it reveals that “upstream,” or top-down approaches, are likely to fail even when they are well-intended, due to the distance between donors and recipient’s preferences. In addition to adverse consequences, this is another reason to be skeptical of charity and nonprofit organizations as alternatives to multilateral institutions.

Dean Spade published Mutual Aid in 2020, a timely and urgent read in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis. He defines mutual aid as “collective coordination to meet each other’s needs, usually from an awareness that the systems we have in place are not going to meet them. [They] have often created the crisis, or are making things worse.” Mutual aid has been a resistance tactic throughout history, and “is an unbroken tradition among Indigenous people across many cycles of colonialism.” Spade writes that one notable mutual aid program was the Black Panther Party’s Breakfast for Children Program, which was first attacked by the state (police urinated on the food) and subsequently co-opted by the U.S. government’s charity-based federal free breakfast program in the 1970s. By stepping in where state institutions have failed, mutual aid serves as a radical form of organization that threatens the legitimacy of the state itself, as well as its supporting institutions like the police. Mutual aid is thus at the crux of abolitionist logic.

The key distinction between mutual aid and charity is the horizontality of mutual aid, in contrast to the hierarchical aspect of charity which necessarily replicates power dynamics (see Figure 2). By virtue of being decentralized and unburdened by the bureaucracy of organizations, mutual aid can respond to people’s immediate needs within minutes and days (help with rent in a couple of days, groceries for the week, assistance with childcare). It is necessarily hyper-local and organized at the neighborhood level.

Figure 2: Mutual Aid vs. Charity

It may seem as though this hyper-local tactic has no relevance to development assistance, which is necessarily global in scale. Yet, according to Spade, “scaling up” mutual aid networks doesn’t mean making groups larger, merging them at the regional level, but rather “means building more and more mutual aid groups, copying each other’s best practices, and adapting them to work for particular neighborhoods, subcultures, and enclaves.” In this way, “one-size-fits-all” approaches to development can be deconstructed and tailored specifically to the needs of local communities. Supplies can be reflexively responsive to immediate demands rather than organized from above. Simultaneously, groups across regions, countries, and continents can share strategies and even redistribute resources.

Social media provides invaluable opportunities to create linkages of solidarity among such hyper-local networks. Platforms such as Instagram and Twitter have decentralized global communication, allowing direct contact with people on the ground as well as the ability to donate money. At the height of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, organizer Isak Douah bought gas masks to protect young frontline protesters from tear gas, and accepted donations via Venmo. Mutual aid groups have filled the gaps of the government’s failure to respond to the Texas power crisis, with citizens around the country donating to these groups within seconds. In India, local networks that are supporting protesting farmers on the ground are taking donations and posting updates on the protests. By amplifying such information and donation to mutual aid groups around the world, no matter how small, every individual can engage in daily acts of solidarity. Giving has been revolutionized: anyone can give, and crucially, they can give horizontally rather than operating through the middleman of an institution or charity.

Covid-19 has laid bare the limitations of the state apparatus. In a global health crisis, not to mention an ongoing and escalating climate emergency, it is purportedly the duty of governments and multilateral organizations to protect the vulnerable by providing resources as a last resort. However, as we have seen time and time again, those responsible for aid have not only failed to solve the systemic nature of poverty, they have often exacerbated the problem. Charities and nonprofits, subject to their own sets of perverse incentives, are not a viable alternative to rectifying the power dynamic which re-entrenches aid recipients as subjects.

Mutual aid provides a liberatory alternative to the concept of development aid assistance. In addition to participating in mutual aid at home, any individual can easily transfer resources and support social movements happening thousands of miles away. Social media and cash transfer apps have created a new revolutionary potential for global solidarity. Rather than supporting USAID or an NGO that is likely to deliver ambiguous or even adverse results, all of us can now support the source directly. Rather than fighting for liberation within the scope of an imperial project, Escobar would have us reject these institutions altogether. Yet this rejection does not have to be simply an abstract thought exercise: mutual aid is an invaluable mode of praxis as love for our neighbors, our friends, and those we will never meet.