BY JOSH RUDOLPH

Over the summer, US bank regulators announced that the eight largest US banks will have to maintain leverage ratios[1] (equity / total assets) of at least 5% for their holding companies and 6% for their depository institutions. This new supplement to the international standard of 3% is a step in the right direction, but should ultimately be taken much further. Higher capital requirements reduce the profitability of banks, but they also provide a buffer against financial crises (like the one in 2008) because the additional equity absorbs losses (like the ones driven by the collapse in house prices). If the buffer is large enough, it saves the government from having to make the unpleasant choice between a bailout (which creates moral hazard) and a banking crisis (which wrecks the economy).

Limiting bank borrowing to no more than 50% of assets (i.e. requiring leverage ratios of at least 50%) makes sense because that’s roughly the average for non-financial companies in the US. In fact, one could argue that banks should have even more equity than that because they have a riskier business model than most non-financial companies and because non-financial companies are surely over-leveraged given that credit is heavily subsidized (both by the interest tax deduction and by massive bank subsidies).

We can’t do away with deposit insurance, because it’s needed to prevent self-fullfilling bank runs. And while regulators are working tirelessly to design an orderly liquidation authority that aims to end this so-called “too-big-to-fail” subsidy, history suggests that creditors rarely believe governmental promises that banks won’t be bailed out in a crisis, particularly after that’s precisely what the government was forced to do in the latest crisis in order to save the economy from a depression.

The only credible way to end the subsidy is by limiting bank borrowing to 50%. This would eliminate both the portion of the subsidy that reaches borrowers (i.e. reduce the availability of credit) as well as the portion that is captured by the financial sector. There are at least five potential arguments against doing this, the last two of which should really concern us.

- Reduced credit supply would slow down the economy. This is bankers’ first response to suggestions of higher capital requirements. But empirically, they have no way of knowing this is true. Likewise, we have no way of knowing it’s false. But nobody worries that the economy doesn’t have enough physical factors of production (e.g. energy/automobiles/computers) if we don’t subsidize Exxon/Ford/IBM. Why is credit any different? It’s also worth pointing out that the economic growth that would be lost by reducing the availability of credit might be at least partly mitigated by the benefits of having a more stable economy. Recessions would be less frequent and less severe, which would enhance savers’ willingness to lend long-term, which would support capital formation. Nevertheless, we cannot dismiss the growth concern entirely. The fact that nobody knows what impact higher capital requirements would have on economic growth does speak to an uncertainty here, which must be weighed as a risk of increasing capital requirements.[2]

- Credit is a public good. Advocates of home ownership point to correlations between owning a home and characteristics of good citizenship, such as working, voting, and obeying the law. But correlation clearly doesn’t prove causation. And even if it is true that home ownership causes good citizenship, I’m inclined to believe we should expect our government to develop more targeted ways of supporting low-income first-time home buying in a way that is cheaper and less distortionary than backstopping unlimited taxpayer resources behind the largest financial system the world has ever seen.

- Government should stay in the business of banking to provide credit in times of stress. A political appointee recently suggested to me that the present environment (whereby the government backs nearly all mortgage origination) demonstrates why the government should stay involved in housing finance. If it wasn’t for Fannie and Freddie, no new homes would have been affordable ever since the financial crisis. One potential response to this is that it’s the job of independent central bankers to be lender of last resort, not the job of politicians. If Treasury hadn’t taken Fannie and Freddie into conservatorship, the Fed should have done something. The distinction is important, because politicians are incentivized by the electoral cycle to believe there’s never such a thing as too much credit.

- Unintended consequences are poorly understood. Before even worrying about “unknown unknowns,” the biggest “known unknown” relating to raising capital requirements is that reducing the profitability of traditional US banking will push intermediation into shadow banks and foreign banks, further from the eyes and tools of regulators. This risk calls for careful monitoring and preemptive prudence by monetary authorities, as well as better coordination both among domestic regulators and across borders. But it does not call for simply throwing up our hands and assuming we can’t do better.

- Transition costs would be enormous. If the Fed announced tomorrow that it’s jacking up leverage ratios from 3% to 50% and banks will not be bailed out, equity and housing markets would probably collapse to deeper lows than the bottom of the recent crisis and the economy would fall into a Second Great Depression. Like sending manual labor jobs overseas, 50/50 banking may be the right thing for us longer-term, but we’ll never get there unless we spread the transition across a couple decades in order to avoid unmanageable disruption to people’s lives. Alex Jutca estimates that incumbent banks would have to retain a generation or two of earnings before reaching 50%.

Whereas those reasons against limiting bank leverage are not entirely satisfying, the reasons to limit the enormous subsidy granted to the financial sector by taxpayers are highly convincing. Most frequently cited are the drag on taxpayer resources and the instability produced by a fragile financial system and an over-leveraged real economy. But perhaps even more deeply troubling is the enormous portion of our country’s financial and human capital that is absorbed by a highly subsidized financial system (distortions economists call deadweight losses). I’m inclined to believe that our country would be a better place with more people like my dad (an entrepreneurial computer programmer), my mom (an exceptional nurse practitioner), my little brother (a genius maker of robots) and my little sister (a brilliant writer), and fewer people like me (a rent-seeking financier).

The real reason why the government is so deeply involved in the business of banking is a bad one (hat tip, Raghu Rajan): Voters arguably care more about consumption than income. And in a world where technology has out-paced education, leading to enormous income inequality, politicians find it easier (in time for the next election) to use the financial system to provide credit to their falling-behind constituents than it is to produce an environment where educated people and law-abiding businesses can find new ways to improve the human condition.

Our leaders owe us more than the status quo and increasing bank capital requirements may be a way to reduce distortions to resource allocation, free up public resources, and induce our politicians to work harder.

Josh Rudolph is a 2014 Master in Public Policy candidate at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, focusing on international trade and finance. Before coming to the Harvard Kennedy School, he was an investment banker and fixed income strategist.

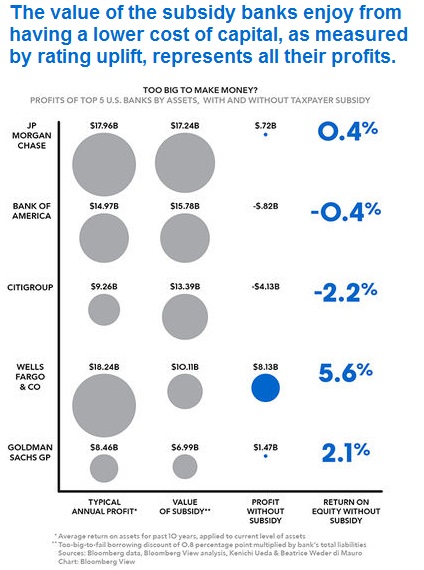

Chart source here. Photo source here.

[1]“Leverage ratio” refers to a bank’s tier 1 capital / total leverage exposure, where the denominator is total assets plus certain off-balance sheet exposures and is not risk-weighted. It should really be called an “equity ratio” because a higher requirement increases equity and reduces leverage. In this note, I use it interchangeably with “capital requirements”, but other people use the latter to refer to total equity / risk-weighted assets (risk-weighted assets are currently about half of total assets).

[2] Some people warn that 50/50 banking (50% equity/assets) has never been done before, but this isn’t true. Until the late 1800’s, banks didn’t enjoy limited liability protection, which despite making banks’ creditors more inclined to lend to banks also made banks’ owners less inclined to take on too much borrowing, and thus equity levels were 40-50%. Today’s bankers will be quick to point out that economic growth was indeed much lower back then, but correlation is not causation (especially with only two data points) and higher growth over the past 150 years probably has more to do with the industrial revolution than the supply of credit. Bottom line, even though it’s been done before, we have no idea what the impact on growth would be of returning to 50/50 banking.