Congress, connected

(by a Harvard summer fellow),

http://ConnectedCongress.org

Philip Harding has a way of persisting in the face of doubt.

During his fellowship on Capitol Hill this summer, Harding, a Kennedy School student, decided to tackle a question that many young adults have asked themselves about their representatives, despite outright effort to dissuade him otherwise. He wanted to learn why Congressmen are surprisingly unaware of the power of today’s technological advances, and what could be done it.

Had Harding known obstacles in store for him, he might have reconsidered.

In contrast with many young adults’ fondness for being wired in, the sentiment on the Hill toward Instagram, Twitter and Facebook tended to be either strong aversion, or hope that social media, which many viewed as merely a trend, would soon fade. Many viewed technology as more a distraction than a tool. Though there were some exceptions, Harding found that Congressmen generally showed little appreciation for the powerful technologies at their disposal.

Harding first needed to change the way Congressional leaders thought about technology. He devoted his summer to reframing the conversation around technology and politics—to convince Congressmen that technology can be a tool for better governance.

“Technology is allowing for much more than just communicating with constituents; technology is becoming central to an effectively functioning congressional office,” Harding said. “That’s why having these discussions is so important at this point in America.”

With support from the Kennedy School’s Center for Public Leadership, Harding founded “Connected Congress,” a non-profit that brought in companies such as Google, Twitter, experts from think tanks and tech firms, and digital proponents from the House and Senate to talk with members of Congress and high-level leaders on the Hill. The goal was to help representatives and other leaders think creatively about how they might improve constituent engagement with technology.

“The idea for Connected Congress was to bring together thought leaders and real-world practitioners straight to the Hill,” Harding explained. “A lot of people in this space talk about how Congress should be doing more to connect with constituents, so I thought, ‘Let’s go talk with them, and try to push these ideas forward.’”

In the beginning, Harding encountered skepticism that any Congressmen would attend the Connected Congress talks; he himself was nearly convinced his idea would fail.

But Harding persisted, setting up meetings with key members of the House and Senate to pitch his idea and build momentum. In total, Harding arranged 40 meetings in a three-week period with Congressional offices, technology firms, and administrative offices to build support, create awareness and finalize logistics.

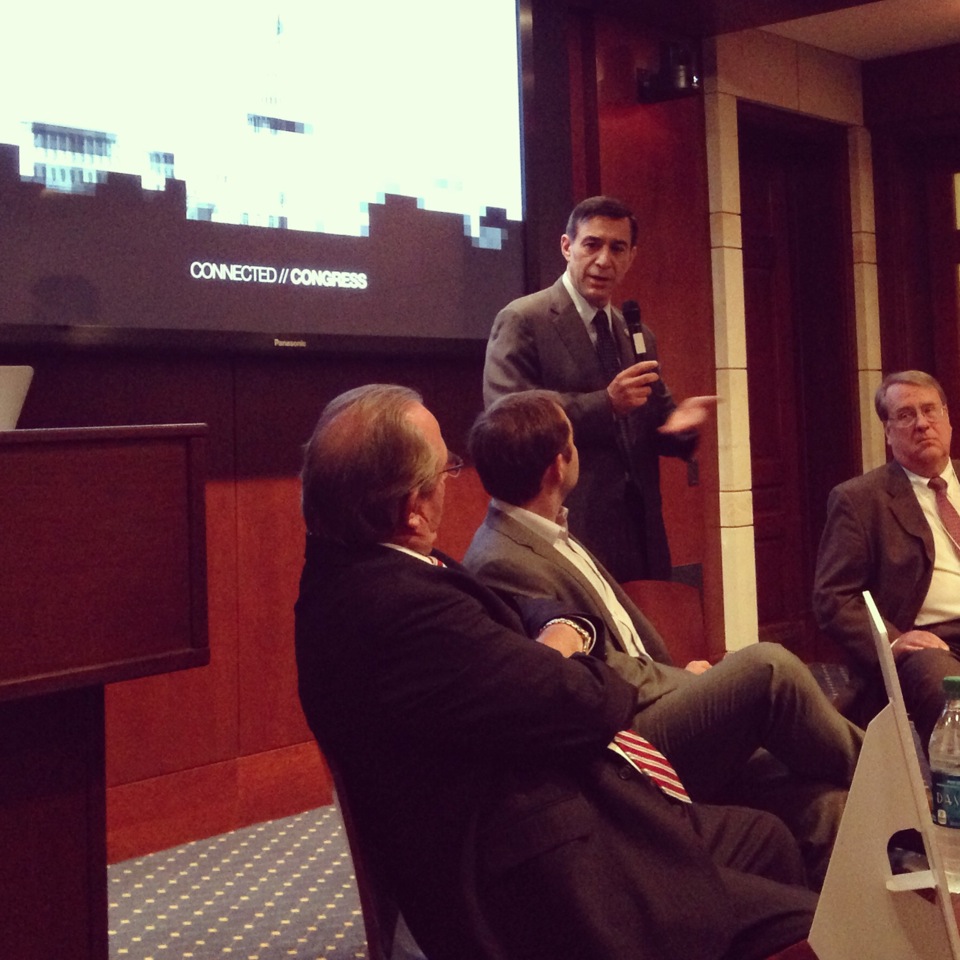

His efforts paid off. Congressmen Darryl Issa (R-Calif.), well known for his mastery of social media tools on the Hill, and his Director of Communications, Justin DeLong, joined the initiative. The offices of other representatives, such as Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-Calif.), and other senior Congressional officials learned of the technology series and asked to get involved.

Before he knew it, Harding had the support of more Hill heavyweights. Interest spiked almost overnight. Emails, messages and phone calls flooded the Connected Congress inbox.

The idea caught on in Congress. At the bipartisan Connected Congress technology series in the U.S. Capitol, Harding was joined by top Congressmen, senior congressional staffers, leaders in the technology space on Capitol Hill and private sector professionals. Several Harvard students working in DC over the summer helped Harding manage the event. The three days of panels, with over 20 speakers in total, were well attended; even when Barack Obama was speaking down the hall, many people instead opted to listen to Connected Congress forums spread quickly, and more members of Congress joined for later sessions.

Harding’s idea of getting Congress members engaged in the conversation was working. For him, this summer would be just the beginning.