The Protest

I was thumbing through my Facebook timeline on my cell phone on a warm summer weekend afternoon when I first saw it. The picture of Mike Brown’s dead body, his blood on the concrete in a long red line. It made me sick to my stomach. My mind started playing the song “Strange Fruit” by Billie Holliday, “Blood on the leaves . . . Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze.” I keeled over a bit and had to stop what I was doing. That song puts into harmony a uniquely discordant American tradition: lynching. This was when a young Black man, and sometimes a woman too, faced extrajudicial murder after being accused of committing an infraction against a White person. They could have been accused of a serious crime or a minor breach of decorum. Either way, the infraction itself was often a pretext. The real crime? Failure to engage in the genuflections demanded by racial hierarchy. For example, Emmett Till wasn’t killed for whistling at a White woman. He was killed for failing to act submissive enough in the Jim Crow context.

Often, they were hung from a tree. The dead body was usually left in plain view as a spectacle, a warning to other Blacks: next time, this would be them.

For decades, the law turned a blind eye to these murders. Police, prosecutors, and grand juries failed to hold the killers accountable. This was unjust justice, when the system itself makes a mockery of what the law is supposed to deliver.

Teenager Mike Brown—stopped for jaywalking, unsubmissive, killed, body left on display for over four hours—trigged these cellular memories inside of me. The devaluing of his life was a devaluing of my own life, the offense to his dignity an offense to my own dignity, the attack on him an attack on the entire community. It was a fresh cut in an old wound.

So I joined and protested. Out on West Florissant Avenue, I saw things that I will never forget. Like Emmett Till’s murder a generation ago, Mike Brown’s killing seemed to mark a turning point. And we, the protestors, in spite of all our subalternity, committed our minds, bodies, and spirits to the task of transforming the meaning of Mike Brown’s killing—sparking once again a movement that included mass civil disobedience and reconceptualizing of fairness and equal justice under the laws of the United States.[1]

The system met our acts of courage not with coronation but condemnation. I saw people chanting, marching, and facing tanks and rows of police without regard to their own safety. I saw people stare down the barrel of loaded police guns pointed in their faces, with police shouting curse words and threatening to shoot them. I saw grandchildren of Freedom Riders labeled as “rioters” and “looters,” as authorities ascribed responsibility to thousands for the acts of a dozen or so individuals.

I saw the people just stand there with nothing to defend themselves but their bare hands in the air, and they kept protesting.

In the protest, I too was tear-gassed, I too had loaded guns pointed in my face, I too was verbally abused and threatened by police officers. They would hem us in and tell us to walk in opposite directions at gunpoint. They told us that we could not stand still in one place for more than five seconds or else we would be arrested. They wore “I am Darren Wilson” wristbands and said things like, “I’m going to Mike Brown you.”[2] In response, we shouted, “Hands up, don’t shoot” with our hands in the air. I gained courage from the energy of the community’s unnamed heroes who face state violence in the hope of finding justice.

In the aftermath, a new Black political discourse emerged from these unheralded heroes. The moment had become a movement, the spontaneous chants had coalesced into mantras, and these mantras struck with force of an obvious idea that stunningly wasn’t obvious: “Black lives matter” as an assertion of value; “Hands up, don’t shoot” as a reconfiguration of who is the savage aggressor and who is the civilized victim appealing to higher angels to no avail; and “I can’t breathe” as a summation of an entire community’s state of being.

The tear gas, rubber bullets, and arrests of hundreds of peaceful demonstrators were acts of violence committed by the state later “justified” through the use of jurisprudential sleight of hand and false legal narratives. But such a scheme fits the character of a system that has been hypocritical since its inception. As Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall noted in his bicentennial speech, the Framers of the Constitution engaged in the “contradiction of guaranteeing liberty and justice for all, but denying both to Negroes.”[3] While our Constitution professed freedom, it practiced slavery. It is difficult to imagine anything more hypocritical.

The fight continued in the following weeks as a struggle for the narrative. Politicians and mainstream media outlets sought to minimize what we had experienced, to justify the actions of the police in the killing of Mike Brown, to rationalize the warlike response to the protesters. State, local, and federal government actors varied in their responses, from patronizing, unresponsive, and clueless, to outright betrayal and abandonment. In light of the failure of these organs to properly function, we decided to petition the United Nations (UN) for redress. Mike Brown’s life is—and all of our lives are—that important to us.

Trying the System

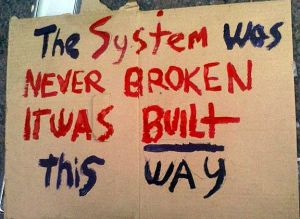

If the legal system in the United States was an animate being, such that it could stand trial, face charges, and at some point encounter an ultimate judgment day, would it be deemed “guilty as hell?” When protesters chant the serious charge that “the whole system is guilty as hell,” do they have evidence to corroborate their claim?

Certainly they could refer back to the Constitution’s framing, Plessy vs. Ferguson, or the Dred Scott case. They could point to the legalized raping of Black women during enslavement, or the lynchings during Jim Crow. The system, in its own defense, would disclaim these crimes, or perhaps one day countenance them making amends and reparation. I, however, don’t know of any justice system that exonerates offenders without penalty simply for disclaiming past acts without any punitive or reparative measures. Nevertheless, does the system continue to commit crimes for which it could be indicted by a grand jury of its peers?

The Crimes

Any system that targets the least powerful and lacks a nationwide sense of urgency to alter its practices embarks on the road to moral bankruptcy. If the system was an animate spiritual being, it would be found guilty and condemned to hell.

Mass Incarceration. Blacks make up only 13 percent of the country, but nearly 43 percent of the combined state and federal prison population.[4] They represent 12 percent of the total population of drug users, but 58 percent of those in state prisons for drug offenses.[5] While the rate of drug use among Whites is five times greater than Blacks, Blacks are imprisoned for drug offenses at a rate ten times greater than Whites.[6] Only an abiding narrative of Black criminality could justify this disparity in punishment. To maintain any semblance of integrity, the system’s defenders must consistently imply, if not outright argue, that Blacks commit crimes at a higher rate than Whites.

Guilty as hell.

Militarized Policing Culture. Police departments have moved from community policing to “hot spot” policing tactics. The use of military language, such as waging a “war” on drugs has a negative effect on our policing cultures. Many departments continue to recruit former military veterans without retraining them to properly engage with community members in a nonmilitary setting. Some have posttraumatic stress disorder and think they are on the streets of Iraq when patrolling our neighborhoods. Some see every person of color in these neighborhoods not as citizens but as targets or enemy soldiers where they have to kill them first or be killed. We saw this demonstrated recently in Miami, Florida, where police unapologetically used the faces of Black men from the community as target practice in their training modules.[7]

These war zones of the mind are then reinforced by programs like the federal government’s 1033 program. Under this program, excess military equipment, like assault rifles and mine-resistant tanks, is provided to local law enforcement agencies upon request with little oversight. During their response to the Mike Brown protests, the Ferguson police had more equipment than had by many soldiers in Iraq, only they did not have the specified training. So they ran around like little children with new toys, playing tag or paintball with people’s lives.

A militarized state also affects day-to-day policing. Soldiers on the battlefield act accordingly on the front lines, veering to use deadly force against reciprocal attempts by enemy combatants. However, when translated into our neighborhoods and in the context of Black criminality, a militarized state facilitates interpretations of the Black body as a perpetual threat.

Guilty as hell.

Lack of accountability for police killings of Black people. The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement estimates that Black youth are killed by law enforcement every twenty-eight hours.[8] Yet, we have consistently failed to even issue indictments. While use of force standards are partly to blame, systemic discrimination and false narratives of Black criminality also induce a lack of accountability within these contexts. For example, in the Mike Brown case, Missouri’s anachronistic and unconstitutional use of force statute gave Darren Wilson an advantage in the grand jury process. Its tenets would potentially justify an officer’s use of deadly force to subdue someone suspected of a nonviolent felony—like passing a bad check.[9] Though the Attorney General of Missouri acknowledged the unconstitutionality of this statute, such practices are apparently not an aberration.[10] Yet, even if these unconstitutional laws cannot stand in court, prosecutors like Bob McCullough of St. Louis County, may still use them to manipulate grand juries and prevent the fair administration of justice.

The President of the United States and others have recommended the use of body cameras to provide more evidence of police interactions. My fear of this policy is twofold: first, that footage will be used and manipulated, leading to further prosecution of minor violations and mass incarceration of Black and brown people; second, as the Eric Garner decision demonstrates, providing more evidence makes no difference if the law itself allows police to kill with little justification.[11] Such a policy may even increase violent encounters as footage is shared of what type of violence has been permitted with impunity.

Guilty as hell.

The International Judgment: Concluding Observations of the United Nations Committee Against Torture

Who would judge the guilt or innocence of the system? In a system that employs mass incarceration, justifies a militarized police culture, and lacks accountability in the practice of its own laws, how could a judgment be rendered from a neutral position?

Through the United Nations, we sought to employ a human rights framework and highlight the ethical nature of this crisis. We traveled to Geneva with Mike Brown’s parents and local Ferguson activists to argue our case before the global community, hoping that we could receive an honest verdict on the behavior of our local, state, and federal officials based on standards of international human rights law.

Black people in the United States have a long history of appealing to the international community, and particularly the United Nations (UN), for judgment of the American system. In the early 1920s, Marcus Garvey petitioned the League of Nations to begin the decolonization process in Africa.[12] In 1947, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) petitioned the UN Commission on Human Rights to investigate the socioeconomic conditions experienced by Black Americans. In “An Appeal to the World,” written under the guidance of W.E.B. Dubois, crafters carefully documented racial inequalities in education, housing, employment, and health care.[13] In July 1964, Malcolm X asked for a formal resolution condemning the United States for human rights violations in its treatment of Black Americans. To a conference of newly independent African nations as part of the Organization of African Unity, he explained that “racism in America is the same as that in South Africa.”[14] Though neither the UN nor the international community made significant interventions as a result of these petitions, their submission brought attention to inconsistencies and injustices employed by a global “leader.” The petitions rightfully altered the facade of a sparkling United States.

In our case, we spoke of the grave injustices of mass incarceration, militarized police culture, and an unaccountable judicial structure. In our case, we noted not only the killing of Mike Brown. We also noted the failure to remove his body for over four hours from the street. We noted the wearing of “I am Darren Wilson” wristbands, wristbands that continue to be worn openly by police officials as of 28 January 2015.[15] We also noted the common practice of smearing the name of deceased victims, as Ferguson Police Chief Thomas Jackson demonstrated by releasing a provocative video of Mike Brown unrelated to the incident involving Darren Wilson.[16] Through these actions and countless others, including its draconian response to the demonstrations, our local police departments have treated citizens of color with more derision that any foreign enemy on a battlefield or in a theater of war.

After our testimony before the United Nations Committee Against Torture, the responses from UN officials made it apparent that the state of policing and the criminal justice system in the United States has damaged America’s moral standing in the global community. During the hearing, multiple committee members questioned the United States government delegation with shock about its failure to put into place effective accountability mechanisms or ensure equal application of the law when it came to criminal justice and the Black community. After the hearing, the UN Committee Against Torture officially expressed its concern about the “numerous reports of police brutality and excessive use of force by law enforcement officials, in particular against persons belonging to certain ethnic groups.”[17] It also expressed its “deep concern” about “the frequent and recurrent shootings or fatal pursuits by the police of unarmed Black individuals,” and it noted the “alleged difficulties of holding police officers and their employers accountable for abuses.”[18] The United States is expected to answer these concerns in the coming months pursuant to the treaty compliance review process.

America was guilty as charged.

Upon our return from Geneva, we felt both legitimized by the international community, and saddened that we had to travel halfway across the world to have our dignity legitimized. In this historical moment of flux, our society has an opportunity to choose to create a new ideal of law enforcement and policing, one that engages human rights and dignity. For the police, it would entail giving up a general culture of militarization and impunity, and being held accountable financially and professionally for excessive use of force and racial profiling in Black and brown communities. Below are a number of policy recommendations that begin to address some of these issues.

Policy Recommendations

* Create standards in compliance with UN human rights norms for the use of force. The Eighth United Nations Congress adopted its “Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials” in 1990. It states that law enforcement should not use firearms against people unless less extreme means are insufficient and should not seek to kill people unless strictly unavoidable to prevent loss of life. It also states that force should not be used to disperse unlawful assemblies, or the least amount of force possible should be used.

* Create financial penalties for police departments that engage in racial profiling. Serious proposals to end harmful practices by government agencies attach funding penalties, the loss of licensing, or the merger of departments as consequences for the lack of compliance. No one has yet proposed this type of firm commitment to ending racial profiling in the United States. Racial profiling creates moral decay in our police departments and facilitates dehumanization and brutality. This must be addressed using financial penalties.

* End the 1033 program and use of military language in training. Giving police high-level military equipment without training promotes irresponsible usage. The alternative of training police to use this equipment further inculcates the militarized culture of an occupying army at war with citizenry. The transfer of this military equipment to state and local police should end.

* Create federally operated oversight mechanisms with enforcement power for civilian review boards. Civilian review boards established around the country have had limited success in changing policing culture. These instruments are easily rebuffed by police departments that can refuse to comply or use their discretion in implementing penalties. Further, such mechanisms fail to recognize victims of brutality as the center of redress. Enforcement mechanisms like subpoenas, additional oversight, and the provision of remedies will help increase the accountability and functionality of these boards.

* Mandate personal liability insurance for police officers. Personal liability insurance can provide a financial incentive for police officers to refrain from misconduct. While current proposals only address extreme cases of police violence that end in the killing of victims, in civil cases, police are generally indemnified from financial penalty by their departments. Officers should face higher premiums when they continuously engage misconduct that raises the probability of a civil suit, perhaps providing them a financial incentive to refrain from misconduct.

* Provide citizens with the right to a hearing with any officer in the aftermath of a police interaction or use of force. This will promote the dignity of citizens and ensure that officers engage in only justified policing activity.

* Disallow the use of deadly force for minor violations. In part, the moral abhorrence of the killing of Eric Garner for selling loose cigarettes and Mike Brown for an interaction that began with jaywalking results from notions of disproportionality between the offense and subsequent police encounter. Deadly force should only be allowed when an arrest involves a felony or serious crime.

Conclusion

We hope our efforts at the UN ultimately result in the creation of more rights, the enforcement of existing rights, and the generation of opportunities for international discourse on issues of racial profiling and police brutality against Blacks in the United States. Ultimately, policing is simply the tip of the spear—mass incarceration is the most devastating attack on Black Americans, and perhaps the greatest ethical failure of our society is failing to even name it as so for decades on end. Our charge remains to fight it on all fronts.

The killing of Mike Brown, like Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, John Crawford, Ezell Ford, Oscar Grant, and so many others, should shock and sadden us all. Any community that instinctually justifies the killing of unarmed citizens (and even children) by its law enforcement has reached a level of moral decay that approaches depravity. The culture of policing and mass incarceration in the United States is not a civil rights issue. It’s a human rights issue. Until it is fixed and reparations are given to the victims, the whole system is guilty as hell.

Endnotes

[1] For more on the work of the altern in meaning creation, see Martha Minnow, ed., Narrative, Violence, and the Law: The Essays of Robert Cover (University of Michigan Press, 1993), 101.

[2] Simon Tomlinson, “’You White Supremacist Motherf*****’: Mass Brawl Erupts at City Hall Meeting to Discuss Civilian Oversight of St. Louis Police in Wake of Michael Brown Shooting,” Daily Mail, 29 January 2015.

[3] See Remarks of Thurgood Marshall at the Annual Seminar of the San Francisco Patent and Trademark Law Association.

[4] See Federal Bureau of Prisons, Statistics, Inmate Race, 24 January 2015; and NAACP Criminal Justice Fact Sheet, NAACP.org.

[5] Ibid.

[6] NAACP Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.

[7] Michael Winter, “North Miami Police Use Faces of Black Men as Targets,” USA Today, 15 January 2015.

[8] Tongo Eisen-Martin, We Charge Genocide Again, Malcolm X Grassroots Movement.

[9] Chad Flanders, “Commentary: Missouri’s Use of Force Statute Goes Against Constitutional Rulings,” St. Louis Public Radio, 25 August 2014.

[10] M. Alex Johnson, “Missouri Attorney General Wants Tougher Deadly Force Law,” NBC News, 3 December 2014.

[11] Justin Hansford, “Body Cameras Won’t Stop Police Brutality. Eric Garner Is Only One of Several Reasons Why,” Washington Post, 4 December 2015.

[12] Amy Jacques Garvey, More Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey (London: Routledge, 1977), 198.

[13] Carol Anderson, “A ‘Hollow Mockery’” African Americans, White Supremacy, and the Development of Human Rights in the United States,” in Bringing Human Rights Home, eds. Cynthia Soohoo, Catherine Albisa, and Martha Davis (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007), 84.

[14] Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (London: Penguin Books, 2011), 361.

[15]Tomlinson, “’You White Supremacist Motherf*****’.’”

[16] Meg Wagner, Joe Kemp, and Corky Siemaszko, “Ferguson Cop Darren Wilson Didn’t Know Michael Brown Was Robbery Suspect at Time of Shooting, Chief Admits as Teen’s Backers Cry Character ‘Assassination,’” New York Daily News, 15 August 2014.

[17] See “Concluding Observations on the Combined Third to Fifth Periodic Reports of the United States of America,” United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 19 December 2014.

[18] Ibid.