Introduction

The usage of assisted reproductive technology (ART) has grown immensely around the world, and future increases are expected.[i] The global market is expected to grow at the compound annual growth rate of 10 percent until 2025.[ii] Surrogacy, the process of a surrogate mother carrying and delivering a child on someone else’s behalf, is one such infertility treatment.[iii] In gestational surrogacy, the intended parents’ egg and sperm is used to create an embryo through in vitro fertilization (IVF). This embryo is then implanted into the surrogate.[iv] Commercial surrogacy involves financially compensating the surrogate mother for this procedure.

India is currently the largest provider of commercial surrogacy services in the world.[v] The total cost of the procedure in India can range from $20,000 to $45,000 in comparison to $60,000 to $100,000 in the US.[vi] The number of surrogacy births in India tripled between 2007 and 2009.[vii] The Confederation of Indian Industry estimated commercial surrogacy to be a 2 billion dollar industry by 2012, and the Indian Council of Medical Research, before recent regulation, expected those numbers to rise to 6 billion dollars by 2018. Despite its increasing importance, commercial surrogacy has largely been an unregulated industry in India for the past 2 decades.

The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill of 2019 aims to regulate this industry.[viii] It places a ban on commercial surrogacy and allows altruistic surrogacy for infertile Indian couples. To be eligible for altruistic surrogacy, the couple needs to have been married for at least 5 years and needs to obtain certificates verifying either partners’ infertility from new regulatory bodies. The bill stipulates that LGBTQ+ families, single parents, unmarried couples, foreign citizens and people outside the age groups of 23-50 for females and 26-55 for men are not permitted to seek surrogacy. Furthermore, only “close relatives” (undefined) of the intended parents can be altruistic surrogates for them. Moreover, surrogate women need to be between the ages of 25 and 35 and can only be surrogates once. Intended parents (IPs) can be punished with up to ten years imprisonment for paying a surrogate mother beyond a “reasonable” amount for insurance coverage for 16 months covering postpartum delivery complications. [ix] This bill has created significant controversy due to appealing government decisions to allow or deny surrogacy, and most importantly, lack of provisions to ensure the altruistic surrogate is not exploited.[x]

Most of the debate surrounding regulation of surrogacy has centred on the morality of the process.[xi] It is arguably a form of commodification of reproductive labour and the women’s body.[xii] Furthermore, since surrogacy involves payment for the act of production of a child, some scholars criticize it as the sale of babies.[xiii] The power dynamics between the intended parents (IPs) and the surrogate also elicit discomfort, wherein women with economic and racial privilege gain control over women’s bodies from the global south.[xiv] The offering of high sums of money to women in extreme poverty can also be construed as coercive, since refusal is difficult.[xv]

On the other hand, we cannot simply assume that surrogate women are incapable of making any real choices. They decide to enter this process after considering the economic alternatives available to them. Surrogates themselves have expressed dissatisfaction with India’s 2015 ban on transnational surrogacy because they found it a meaningful source of income.[xvi] Power imbalances and coercion exist in most jobs available to Indian lower-class women. This paper will therefore consider how to minimize those risks within surrogacy and will engage with the concerns of commodification and exploitation more directly.

Method

This paper aims to research the potential impacts of India’s ban on commercial surrogacy and proposes an alternative model. Its objectives are (1) to understand the current impacts of commercial surrogacy on surrogate women, (2) to understand the likely outcomes of the ban on the surrogacy industry and on women who previously chose to become surrogates, (3) to evaluate the ethical arguments for a ban on commercial surrogacy, and (4) to suggest regulatory measures to enhance the best interests of all parties involved in commercial surrogacy in comparison to a blanket ban. It relies on both primary data, i.e. interviews with subject matter experts based on a purposive sample, and secondary data, such as books, journals, speeches and reports.[xvii]

The paper reaches the conclusion that the ethical arguments made for a ban fall short of proving the need for the ban. Through qualitative findings from the interviews and case studies in other countries, the authors expect that the ban would worsen an underground market and increase the coercion of women into altruistic surrogacy. An alternative regulatory framework is proposed that promotes the best interests of the involved parties while resolving, to the greatest extent possible, the structural problems with surrogacy.

Ethical background

Many people support a ban on commercial surrogacy due to moral discomfort. This paper engages with commodification and exploitation concerns specifically, since they are most frequently debated.

Commodification of the body and the child

Commodification refers to making something available for sale and purchase in the market, or treating something like a commodity.[xviii] There is debate over whether the payment in commercial surrogacy is for the service of reproduction, for control over the woman’s body, or for the child as a good.[xix] The paper will next present counterarguments to these potential concerns.

Payment for the child

One of the largest set of objections to commercial surrogacy relate to corruption, i.e. that the market will denigrate the value of children. There is fear of both consequentialist corruption, wherein the meaning individuals attach to children will change in a manner that leads to negative consequences, like an increased risk of demanding payment for adoption, and of intrinsic corruption, in which regardless of the outcome, the act of putting a price on a child demeans children.[xx]

There are multiple counterarguments to intrinsic corruption. Firstly, even in the case of miscarriage of the baby, the clinic is paid.[xxi] This signals that the payment made is in fact for the service of carrying the child and not for the child as a product.[xxii] Secondly, as noted by Judge Sorkow in the legal case called “Baby M,” intended parents already have a genetic tie to the surrogated child.[xxiii] They cannot be “buying a child” because regardless of money, the child is at least partly theirs.

It also cannot be empirically proven that commercial surrogacy denigrates children.[xxiv] In fact, numerous ethnographic studies show that both IPs and the surrogate highlight the “gift” nature of giving the child away to the IPs.[xxv] The love expressed by IPs cannot be proven less meaningful than that expressed by biological or adoptive parents, especially considering the extensive lengths they have gone to in order to become parents.[xxvi] Lesser negative parenting has been observed in gestational surrogacy families when compared to families with children born through gamete donation.[xxvii] Unless it is concluded that the perceptual harm to children is equivalent to the abuse for which states take children away from parents, surrogacy should not be banned on the grounds of consequentialist corruption.

Payment for reproductive labour and the woman’s body

Another set of commodification concerns deal with payment for reproductive labour. Many media references to surrogate women as “wombs for rent” display an underlying anxiety regarding an Atwood-esque world.[xxviii] Commercial surrogacy has therefore been compared to practices like organ sales because of the control of a woman’s womb for nine months for the exchange of money.[xxix] However, any worker has restrictions placed on their bodily autonomy for payment, such as being forced to enter a coal mine regularly and endanger their health. The problem arises when the degree of control rises beyond what we normally accept. Legal protections will be able to guard against any clinic’s potential attempt to control the surrogates’ bodily freedoms to an unusual or harmful extent.

Some scholars compare commercial surrogacy to prostitution and argue that women’s sexuality or reproductive labour should not be commodified. However, many forms of labour are intensely intimate, so this objection to commercial surrogacy is therefore non-unique, like wet nursing and sperm donation.[xxx] Many of the current objections to commercial surrogacy resemble historical objections to female dancers which arose from discomfort with female sexuality rather than the immorality of the transaction. Panitch states that if the arguments for the uniqueness of reproduction were based on the extent of bodily control that comes with reproductive labour, we would also oppose working in mass production or the military.[xxxi]

Exploitation

Literature on surrogacy mentions the exploitative nature of the power imbalance between the upper-class intended parents and the surrogate mother as a strong argument against its legalisation.[xxxii] Other aspects of surrogacy, like the health risks, gender-based exploitation, and insufficient compensation, among others, also rightfully elicit concerns. However, because most of these can be dealt with through regulation in the future, their existence now is not a reason for a ban.

Sivakami Muthuswamy, the Chairperson of the Centre for Health and Social Sciences at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, emphasizes the necessity to respect women’s agency. While the researcher concedes that the reproductive choice to be a surrogate would likely not have been made had these women not been poor, we cannot have this discussion while pretending that the context of poverty does not exist. In an ideal world, they would not have to choose to work in sweatshops, as surrogates, or as prostitutes. The choices made by women in poverty indeed are made with its coercive pressure upon them; however, that does not render those choices meaningless. We need to recognise that to the best of their abilities, these women are making the decisions that maximise their welfare. Our responsibility is to ensure they have more choices and more information, neither of which requires a ban on commercial surrogacy.

Furthermore, the exploitative nature of commercial surrogacy needs to be considered with respect to the other job options available to these women. Rudrappa’s A Discounted Life indicates that a significant proportion of women choosing to be commercial surrogates in Bangalore chose it over garment work, where they faced lower pay, sexual harassment, longer working hours and worse health risks.[xxxiii] Similarly, in other parts of India, many of these women were previously employed as domestic help, in factories, or as prostitutes, often with similarly concerning working conditions.[xxxiv] The sum of money offered for commercial surrogacy is often many times their annual income.[xxxv]

To justify a ban, the harms to surrogates must be considered with respect to their conditions before surrogacy. Considering this ethics discussion, the paper will also evaluate the current impact of surrogacy (on surrogate women), and the implications of the proposed ban.[xxxvi]

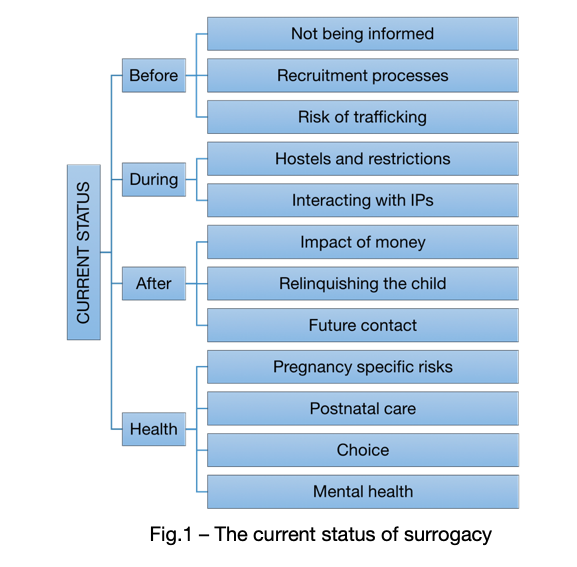

The current status of surrogacy

This section will provide an overview of the process of surrogacy as it stands currently. It examines potential concerns at each stage: before, during, and after surrogacy.

Before surrogacy

Most surrogates are recruited in one of several ways. Firstly, agents, often past surrogates appointed by the clinics, recruit women in their personal networks for a commission.[xxxvii] Ray and Muthuswamy claim that the agents often act as vehicles of misinformation, selectively emitting negative information about the process. Secondly, some women choose to be surrogates after learning about surrogacy through movies or advertisements run by the clinics.[xxxviii] Additionally, the biggest recorded motivations for becoming surrogates is financial compensation or gifting a child to infertile parents.[xxxix] [xl]

In the process of making this decision, many women are not well informed about the process of surrogacy, beyond the knowledge that it does not involve intercourse. A surrogate interviewed by Daisy Deomampo reports “I wanted one copy [of the contract] for myself, but I didn’t dare to ask for one…one page was also blank which I signed and also the amount was not filled in… she didn’t give us a chance to read the agreement.”[xli] More than 90 percent of surrogates do not receive a copy of the contracts they sign and do not participate in the contract drawing process. Furthermore, their illiteracy means that the clinic gets to decide what parts of the contract will be explained. One interviewee referred to women being trafficked for surrogacy in Hyderabad in 2018. The process of choosing surrogacy and entering the process requires greater oversight and transparency, suggestions for which will be included in the regulations section.

During surrogacy

Many surrogate women stay in hostels away from their homes while carrying the baby, at request of the intended parents or to prevent people from finding out that they are surrogates. In these hostels, many restrictions are placed on their freedom. They have specific dietary requirements; some hostels limit visits from their children and family members; surrogate mothers are not allowed to use staircases and spend most time on bed rest; and they are not permitted to have any sexual contact.[xlii]

After surrogacy

Payment

According to reports by the Centre for Social Research, Delhi, 38 percent of the women who chose to be surrogates in Jamnagar, Anand and Surat earned between Rs. 1000 (~$15) and Rs. 2000 (~$29) a month in their normal jobs. In comparison, they can earn anywhere from $2,000 to $8,000 by being a surrogate once.[xliii]

However, although many IPs view transnational surrogacy as a “worthy cause” because of the money they give to the surrogate, the process of compensation is opaque and often unfair. Muthuswamy notes an incidence of an intended couple paying Rs. 12 lakhs (~$17,000) while the surrogate received a measly Rs. 40,000 (~$600). Such stories are not uncommon, since the clinic is usually the mediator in the transaction.[xliv] Often, surrogates are not paid an additional amount for carrying twins or triplets and are not paid at all in the case of a miscarriage.[xlv] Sharmila Rudrappa notes that many hidden costs arise during surrogacy. Clinics require payment from the surrogate for some procedures; the surrogate is unable to work during and after the pregnancy; and family members often quit their jobs to take over her familial responsibilities. Despite this, the one-time payment gives the woman liquid capital that is often spent on repaying debt, medical care of relatives, or for crucial expenditures into small farms. While this money might not change the lives of the surrogates, it enables them to deal with emergencies without putting themselves in greater risk.

Health

There are significant health risks involved in the process of commercial surrogacy. Not only do pregnancy-specific concerns like miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and similar obstetric complications become more likely, many cycles of IVF, hormone treatment and embryo transfer hurt the surrogate’s physical health.[xlvi] The lack of consent and comfort with the institutionalized medical system often worsens these risks because surrogates are unable to communicate their needs.[xlvii] They are often forced to undergo unnecessary C-sections and transvaginal ultrasounds, amongst other procedures.[xlviii] Currently, clinics in India “offer” postnatal care, but charge the surrogates for it, making many surrogate women choose to return to their daily jobs and household chores after the delivery.[xlix] The severe stress imposed by separation from their families, social stigma, and giving up a child they carried also takes a toll on surrogate women.[l] Some studies, however, reveal that many surrogates find the process fulfilling, or in the least, do not face significant difficulties separating from the child.[li]

Implications of a ban

The promotion of altruistic surrogacy

Spriha Shukla, a PhD student in Gender Studies at TISS, states that if the alternative to commercial surrogacy is altruistic surrogacy, it can create the expectation of women being constantly available to engage in excruciating labour if they are pressured.[lii] Nilanjana Ray says, “If you’re stopping people who are willing, you might be opening doors to forcing people who are unwilling.” Within the context of tightly knit Indian families, there is high likelihood of daughters-in-law or other women in the family being guilted or forced into altruistic surrogacy.

Underground markets

An underground market is highly likely to develop with the implementation of a ban due to legal altruistic surrogacy. Muthuswamy pointed to the rampant recorded rise of kidney sales in India despite kidney donations being legally restricted to close family. Fake certificates of familial relationship are easy to procure, and cash transactions easily bypass the law. One can legally pay for medical insurance for the surrogate for a period of 16 months after the birth of the child, making it hard to monitor if the money is exclusively for insurance or includes compensation. It is also possible for health professionals carrying out surrogacy to claim they are simply providing infertility treatment for the surrogate. Furthermore, the demand for infertility treatments is quite inflexible. Infertile parents who have tried many different treatment routes and do not want to adopt are likely to still seek commercial surrogacy.

This is also supported by studies in other countries and markets. It is estimated that over 10,000 children a year are born through commercial surrogacy in China despite the ban on the same.[liii] Many news organisations suggest that India’s 2015 ban on transnational surrogacy was frequently sidestepped by moving surrogates to Nepal and Kenya during the procedure to avoid the law. [liv]

In conclusion, it is likely that commercial surrogacy will continue despite a ban, leaving women who continue to be surrogates unable to demand protections. Even if the underground market does not exist, women who turned to surrogacy for income might work in industries with worse working conditions. Altruistic surrogacy might become more common, which comes with its own harms, like using coercion or force in patriarchal families to make women surrogates.

Recommendations

Based on the current landscape of surrogacy in India and the high probability of a ban further marginalising surrogates, this paper proposes regulation rather than a ban. These recommendations have been primarily informed by One Hundred Second Report of the Rajya Sabha on The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill 2016 and from my own research and interviews.

Regulatory bodies

For the regulation of surrogacy, we propose setting up bodies modelled upon India’s Central Adoption Resource Authority’s (CARA), which functions under the Ministry of Women and Child Development. The Surrogacy Regulation Authority (SRA) can be similarly run at multiple levels—district, state, central.

The charter of the SRA should require it to facilitate fair commercial surrogacy and penalise illegal practices. Individual clinics that plan on conducting surrogacy should need to get licensed by the SRA. The SRA can also create an online portal and toll-free phone number for the purposes of collecting anonymous complaints. In the situation of multiple complaints against a clinic, like delayed payment to surrogates, the SRA can give the clinic a time frame to fulfil the legal requirements or suspend their licenses. Beyond the complaint mechanism, it can conduct monthly surprise visits to monitor if the laws are being followed and impose heavy fines or suspend licenses if they are not. It can also file the criminal reports for imprisonment in the case of repeat violations in specific instances with the police. With these enforcement methods, it will be possible to uncover violations of legal protections for surrogates and create safer working conditions.

The SRA can publish a list of clinics carrying out commercial surrogacy on their website. After intended parents approach a specific clinic, they need to be redirected to the SRA, where they will receive counselling to support their decision. They can also be encouraged to consider other options like adoption. Furthermore, they can get information about the process and an understanding of fair practices from the SRA. This ensures that IPs make an educated decision to seek commercial surrogacy, can report malpractice, and are supported in the process, making it less likely that they seek limited freedoms for the surrogate.

There also needs to be certain restrictions on who can be a surrogate. This paper suggests that the surrogate should be above the age of 21 and have had at least one child prior to becoming a surrogate in order to ensure meaningful choice. There needs to be a gap of a minimum of 2 years between births, and the total number of children she delivers must be 5 or below, including her own children. This is to ensure a surrogate’s health is protected, and that she has the ability to make an informed choice. A surrogate mother, once recruited by the clinic, would need to register with the SRA. She can be given a registration ID that is computerized into an online database encompassing all SRA bodies. In this registration, she would need to provide information like her age and number of children. While agreeing to partake in surrogacy, she needs to be given versions of the contract that are approved by the SRA and available both in audio and written form in her preferred language. Agreement to the contract can only happen after free mandatory SRA provided psychological and legal counselling has taken place, through social workers or members of partner NGOs. Surrogates can also be given the contact details of both the counsellor and the lawyer if they need additional support during the process. Furthermore, the surrogate needs to be given a copy of the contract signed by her. These provisions ensure that surrogates are not exploited in the process of making a contract and have the ability to legally fight exploitation in the future, and that IPs are not lied to about the sum being paid to the surrogate.

The SRA needs to publish regular information sets for each registered clinic with information like the average pay received by the surrogate at that location and display them at the clinics and surrogacy centres to facilitate transparency. This is because reform can also be demand driven; many intended parents express a desire to help the surrogates, and receiving this information can enable IPs to avoid clinics that do not pay surrogates well.

The SRA can also be responsible for conducting monthly or quarterly support sessions for surrogate women – at the clinic, over the phone, or at SRA headquarters – whichever yields greatest attendance. These can include information about their health and the procedures that they are undergoing and can be spaces for surrogate women to interact with each other. Ray points out the importance of community education before recruitment as well, sessions for which can be carried out by the SRA, breaking down the stigma around surrogacy and preventing the agents from being the only information source. These sessions could also make surrogates comfortable with the SRA, making them more likely to report violations of laws.

Legislative provisions

Beyond the structure and basic responsibilities of the SRA itself, the following are specific individual provisions that the law should provide. In the area of health, surrogates should have the ability to opt out of C-sections and unnecessary invasive procedures. There needs to be a limit on the number of IVF cycles a surrogate can undergo, and procedures like multiple embryo transfers should require the surrogate’s consent after proper education. Shukla adds that psychological counselling facilities and mandatory postnatal care should be made available and paid for by the IPs. These are necessary for protecting surrogate women’s agency, physical health, and mental health.

Any payment to the clinic and to the surrogate should not be made in terms of cash to enable transparency and regulation. Assistance for setting up a bank account can be provided by either the SRA or the clinic. The actual sum also needs to be legislated upon – there should be either a legal minimum wage for commercial surrogacy, as suggested by Muthuswamy, or a certain fair predetermined percentage of the amount paid by the intended parents that should go to her, even in the case of miscarriage or death of the surrogate. At least half of the total payment should be given before the birth of the child, in the form of monthly or quarterly segments to create greater control over the income. The SRA can audit the financial records of the clinic from time to time to see if the payments are made in accordance with the rules.

Other recommendations

Beyond legislation, this paper makes a series of recommendations.

- The medical curricula for infertility specialists should also discuss in depth the psychological and legal experience of surrogacy to create professionals that will be able to provide the necessary support for surrogates that work for them.

- States should have a clear policy on transnational surrogacy and the citizenship of surrogated children, similar to the Hague Convention on Adoption, to avoid cases like that of Baby Manji in the future. It is outside the scope of this paper to make recommendations on what that policy should entail.

- As Majumdar suggests, all attempts to improve the condition of surrogates should be accompanied by skill development and education to create sustainable ways to escape poverty. Some surrogacy clinics offer vocational training and English lessons for surrogates in status quo, which can be supported by the State.

Conclusion

In the best-case scenario of the proposed ban, only small portion of the market goes underground, and the rest is successfully shut down. For these surrogates still in the market, the harms of the process increase exponentially. IPs and surrogates scared of breaking the law and stigma would rely on clinics more, losing any ability to complain against violations of the surrogate or IP rights at the clinic. In comparison, the best case of regulation would be some clinics being badly regulated, and most undergoing marked improvement in the treatment of surrogates as a result of the proposed model. Government investment into education and skill development for letting women move away from surrogacy is crucial, but it does not require removing this income source pre-emptively.

Clearly, India can run successful regulatory bodies. While the CARA has been criticised for its slowness, it is quite functional. The National Regulatory Authority, India’s vaccine regulatory body, has been recognised as a success by the World Health Organisation.[lv] Pushing for stronger regulation over the ban leads to the best outcomes in the long run. However, there are many limitations to the suggestions offered in this paper. Not all ethical arguments offered against legalized commercial surrogacy have been considered. The secondary data that the paper is based on is limited due to the newness of transnational commercial surrogacy; it largely consists of qualitative studies rather than large-scale quantitative data regarding the impacts of surrogacy. The model relies entirely on robust enforcement from the SRA and law enforcement, and there are many industries and health-related services that India has failed to adequately regulate. It is possible that many surrogates do not know out about these regulations and continue working in a grey market where clinics are licensed and legitimised, but their actions are not overseen.

In conclusion, the ban on commercial surrogacy proposed by the Indian state is unlikely to achieve its intended consequences. The major ethical arguments against surrogacy do not sufficiently prove the need for a ban, and it is likely to further marginalise poor women and restrict their choices. An alternative route consisting of stringent regulation and enforcement is likely to be in the best interests of all parties.

References:

- Ian Johnson and Cao Li, “China Experiences A Booming Underground Market In Surrogate Motherhood,” The New York Times, 2 August 2014.

- “India Outlawed Commercial Surrogacy – Clinics Are Finding Loopholes”. The Conversation, accessed 28 April 2019, https://theconversation.com/india-outlawed-commercial-surrogacy-clinics-are-finding-loopholes-81784.

- “The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016: Comparison Of The 2016 Bill With The 2018 Amendments,” Prsindia.Org, accessed 28 April 2019, https://www.prsindia.org/sites/default/files/bill_files/Note%20on%20Amendments%20-%20Surrogacy%20Bill.pdf.

- “WHO Finds India’s Vaccine Regulatory Authority Compliant With International Standards”. World Health Organization, accessed 28 April 2019, https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/india-authority_reg_compliant-int-standards/en/.

- Anuradha Nagaraj, “Wombs For Rent: Indian Surrogacy Clinic Confines Women In ‘Terrible…”. Reuters, 19 June 2017.

- “Surrogacy Risks & Side Effects | Surrogate.Com” Surrogate.Com, accessed 28 April 2019, https://surrogate.com/surrogates/pregnancy-and-health/emotional-and-medical-risks-of-surrogacy/.

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine, “Consideration Of The Gestational Carrier: A Committee Opinion,” Fertility And Sterility 99, no. 7 ( 2013): 1838-1841.

- Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Type (IVF, AI-IUI, FER, Others), By End Use (Hospitals, Fertility Clinics), By Procedures And Segment Forecasts, 2018 – 2025, accessed 9 Feb 2019, Grand View Research, San Francisco.

- Peter R. Brinsden, “Gestational Surrogacy,” Human Reproduction Update 9, no. 5 (2003): 483-491.

- Nicole F. Bromfield, ““Surrogacy Has Been One Of The Most Rewarding Experiences In My Life”: A Content Analysis Of Blogs By U.S. Commercial Gestational Surrogates,” IJFAB: International Journal Of Feminist Approaches To Bioethics9, no. 1 (2016): 192-217.

- Centre for Social Research. Surrogate Motherhood – Ethical Or Commercial?, accessed 12 Mar 2019, New Delhi, 2012.

- Daisy Deomampo, “Transnational Surrogacy In India: Interrogating Power And Women’s Agency,” Frontiers: A Journal Of Women Studies 34, no. 3 ( 2013): 167.

- Raywat Deonandan, Samantha Green, and Amanda Van Beinum, “Ethical concerns for maternal surrogacy and reproductive tourism,” Journal of Medical Ethics 38, no. 12 (2012): 742-745.

- Susan Golombok, Elena Ilioi, Lucy Blake, Gabriela Roman, and Vasanti Jadva, “A longitudinal study of families formed through reproductive donation: Parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent adjustment at age 14.” Developmental psychology 53, no. 10 (2017): 1966.

- Jason K.M Hanna, “Revisiting Child-Based Objections To Commercial Surrogacy,” Bioethics 24, no. 7 (2010): 341-347.

- Sarah Huber et al., “Exploring Indian Surrogates’ Perceptions Of The Ban On International Surrogacy,” Affilia 33, no. 1 (2017): 69-84.

- Casey Humbyrd, “Fair Trade International Surrogacy,” Developing World Bioethics 9, no. 3 (2009): 111-118.

- V. Jadva, “Surrogacy: The Experiences Of Surrogate Mothers,” Human Reproduction 18, no. 10 (2003): 2196-2204.

- Esme I. Kamphuis, S. Bhattacharya, F. Van Der Veen, B. W. J. Mol, and A. Templeton, “Are we overusing IVF?.” Bmj 348 (2014): g252.

- Sharvari Karandikar, Lindsay B. Gezinski, James R. Carter, and Marissa Kaloga. “Economic necessity or noble cause? A qualitative study exploring motivations for gestational surrogacy in Gujarat, India.” Affilia 29, no. 2 (2014): 224-236.

- Pawan Kumar, Deep Inder, and Nandini Sharma, “Surrogacy and women’s right to health in India: Issues and perspective,” Indian journal of public health 57, no. 2 (2013): 65.

- Melissa Lane, Surrogate Motherhood, Hart, 2003, 121-139.

- Florencia Luna and Allison B Wolf, “Challenges For Assisted Reproduction And Secondary Infertility In Latin America,” International Journal Of Feminist Approaches To Bioethics7, no. 1 (2014): 3.

- Anindita Majumdar, “The Rhetoric Of Choice: The Feminist Debates On Reproductive Choice In The Commercial Surrogacy Arrangement In India,” Gender, Technology And Development 18, no. 2 (2014): 275-301.

- Piyusha Majumdar, Personal Interview, 3 March 2019.

- Narendra Malhotra, Duru Shah, Rishma Pai, H. D. Pai, and Manish Bankar, “Assisted reproductive technology in India: A 3 year retrospective data analysis,” Journal of human reproductive sciences 6, no. 4 (2013): 235.

- Aniruddha Malpani, “Banning Commercial Surrogacy: Ethical or Regressive?” NDTV

- Sivakami Muthuswamy, Personal Interview, 7 February 2019.

- A. Nakash and J. Herdiman, “Surrogacy,” Journal Of Obstetrics And Gynaecology 27, no. 3 (2007): 246-251.

- One Hundred Second Report- The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016, accessed 1 May 2019, Rajya Sabha Secretariat, 2017.

- Amrita Pande, “Transnational Commercial Surrogacy In India: Gifts For Global Sisters?” Reproductive Biomedicine Online 23, no. 5 (2011): 618-625.

- Amrita Pande, Wombs In Labor. (Columbia University Press, 2014).

- Vida Panitch, “Surrogate Tourism And Reproductive Rights”. Hypatia28, no. 2, (2012): 274-289.

- Bronwyn Parry and Rakhi Ghoshal, “Regulation Of Surrogacy In India: Whenceforth Now?” BMJ Global Health 3, no. 5 (2018): e000986.

- Bronwyn Parry, “Surrogate Labour: Exceptional For Whom?” Economy And Society 47, no. 2 (2018): 214-233.

- Pillai, “The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016: A Critical Appraisal”. Livelaw.In, 2019, https://www.livelaw.in/surrogacy-regulation-bill-2016-critical-appraisal/.

- Nilanjana Ray, Personal Interview, 6 February 2019.

- D. R. Reilly, “Surrogate Pregnancy: A Guide For Canadian Prenatal Health Care Providers,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 176, no. 4 (2007): 483-485.

- Sharyn L. Roach Anleu, “Reinforcing Gender Norms: Commercial And Altruistic Surrogacy,” Acta Sociologica 33, no. 1 (1990): 63-74.

- Sharmila Rudrappa, “India’s Reproductive Assembly Line,” Contexts 11, no. 2, (2012): 22-27.

- Sharmila Rudrappa, Discounted Life, 2015.

- Elizabeth S. Anderson, “Is Women’s Labor A Commodity?” Philosophy & Public Affairs 19, no. 1 (1990): 71-92.

- Elizabeth S. Anderson, “Why Commercial Surrogate Motherhood Unethically Commodifies Women And Children: Reply To Mclachlan And Swales,” Health Care Analysis 8, (2000): 19-26.

- Elizabeth S. Scott, “Surrogacy And The Politics Of Commodification,” Law And Contemporary Problems, no. 72 (2009): 109-145.

- SAMA. Birthing A Market. New Delhi, 2012.

- Sheela Saravanan, “An Ethnomethodological Approach To Examine Exploitation In The Context Of Capacity, Trust And Experience Of Commercial Surrogacy In India,” Philosophy, Ethics, And Humanities In Medicine 8, no. 1 (2013): 10.

- Sheela Saravanan, “Global Justice, Capabilities Approach And Commercial Surrogacy In India,” Medicine, Health Care And Philosophy 18, no. 3 (2015): 295-307.

- Debra Satz, “Markets In Women’s Reproductive Labour” Philosophy And Public Affairs 21, no. 2 (1992): 107-131.

- “Surrogacy Risks & Side Effects | Surrogate.Com,” accessed 10 March 2019, https://surrogate.com/surrogates/pregnancy-and-health/emotional-and-medical-risks-of-surrogacy/.

- Priya Shetty, “India’s Unregulated Surrogacy Industry”. The Lancet 380, no. 9854 (2012): 1633-1634.

- Spriha Shukla, Personal Interview, 24 February 2019.

- Holly Donahue Singh, “The World’s Back Womb?: Commercial Surrogacy And Infertility Inequalities In India,” American Anthropologist 116, no. 4 (2014): 824-828.

- Viveca Söderström-Anttila, Ulla-Britt Wennerholm, Anne Loft, Anja Pinborg, Kristiina Aittomäki, Liv Bente Romundstad, and Christina Bergh. “Surrogacy: outcomes for surrogate mothers, children and the resulting families—a systematic review,” Human reproduction update 22, no. 2 (2016): 260-276.

- Olinda Timms, “Ending Commercial Surrogacy In India: Significance Of The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016,” Indian Journal Of Medical Ethics (2018): 1.

- Hugh V. McLachlan and J. Kim Swales, “Commercial Surrogate Motherhood And The Alleged Commodification Of Children: A Defense Of Legally Enforceable Contracts,” Law And Contemporary Problems 72, (2019): 91-107.

- Kalindi Vora, “Indian Transnational Surrogacy And The Commodification Of Vital Energy,” Subjectivity 28, no. 1 (2009): 266-278.

- Kalindi Vora, “Potential, Risk, And Return In Transnational Indian Gestational Surrogacy,” Current Anthropology 54, no. S7 (2013): S97-S106.

- Stephen Wilkinson, “Commodification Arguments For The Legal Prohibition Of Organ Sale,” Health Care Analysis 8 (2000): 189-201.

[i] (Malhotra et al.)

[ii] (Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Type (IVF, AI-IUI, FER, Others), By End Use (Hospitals, Fertility Clinics), By Procedures And Segment Forecasts, 2018 – 2025)

[iii] (Brinsden); (Jadva)

[iv] (American Society for Reproductive Medicine)

[v] (Rudrappa)

[vi] (Pande)

[vii] (Malhotra et al.)

[viii] (Timms)

[ix] (“The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016: Comparison Of The 2016 Bill With The 2018 Amendments”)

[x] (Pillai)

[xi] (Timms)

[xii] (Panitch)

[xiii] (Hanna)

[xiv] (Luna, and Wolf)

[xv] (Panitch)

[xvi] (Huber et al.)

[xvii] An IVF specialist was interviewed for preliminary research; then, a graduate student studying surrogacy in India and three academics were interviewed, based on a purposive sample. Prof. M. Sivakami, PhD in Population Studies, is a professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai. Her research areas include maternal and child health. Prof. Nilanjana Ray has PhDs in Social Work and Modern History and researches child protection, human trafficking, and women and migration at TISS. Prof. Piyusha Majumdar, PhD in Anthropology, teaches public health at the Indian Institute of Health and Medical Research and has implemented projects in the field of maternal and child health. The interviews were transcribed, and thematic analysis was conducted using Atlas.ti. Spriha Shukla is pursuing MPhil-PhD in Women’s Studies. Most interviewees opposed the ban, and qualitative findings have been integrated into the discussion.

[xviii] (Wilkinson)

[xix] (Sharp); (Humbyrd)

[xx] (Lane)

[xxi] (Rudrappa)

[xxii] (V. McLachlan, and Kim Swales)

[xxiii] The Baby M case was a 1985 court case in the New Jersey Supreme Court about the enforceability of traditional surrogacy contracts.

[xxiv] (S. Scott)

[xxv] (Pande)

[xxvi] (SAMA)

[xxvii] (Golombok et al.)

[xxviii] (“Wombs For Rent: Indian Surrogacy Clinic Confines Women In ‘Terrible…”); Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale follows a dystopian world, Gilead, where fertile young women are captured and forced to reproduce for infertile couples to deal with a falling birth rate.

[xxix] (Majumdar)

[xxx] (Parry)

[xxxi] (Panitch)

[xxxii] (Singh)

[xxxiii] (Rudrappa)

[xxxiv] (Pande); (Centre for Social Research)

[xxxv] (Shetty)

[xxxvi] Many scholars argue that a trade can be exploitative even if it is consensual and mutually beneficial. However, that is a heavily contested claim, and policy decisions need to be made with real world consequences in consideration rather than in an ethical vacuum.

[xxxvii](Saravanan)

[xxxviii](SAMA)

[xxxix] (Karandikar et al.)

[xl] (Vora)

[xli] (Deomampo)

[xlii] (Pande)

[xliii] (See CSR report, Pande’s Wombs in Labor, SAMA’s Birthing a Market, and Rudrappa’s A Discounted Life).

[xliv] (Saravanan)

[xlv] (SAMA)

[xlvi] (Kumar et al.); (Kamphuis et al.)

[xlvii] (SAMA)

[xlviii] (Deonandan et al.)

[xlix] (SAMA)

[l]“Surrogacy Risks & Side Effects | Surrogate.Com”. Surrogate.Com, 2019, https://surrogate.com/surrogates/pregnancy-and-health/emotional-and-medical-risks-of-surrogacy/.

[li] (Bromfield); (Söderström-Anttila et al.); (Jadva); (Reilly)

[lii] (Roach Anleu)

[liii] (“China Experiences A Booming Underground Market In Surrogate Motherhood”)

[liv] (“India Outlawed Commercial Surrogacy – Clinics Are Finding Loopholes”)

[lv] (“WHO Finds India’s Vaccine Regulatory Authority Compliant With International Standards”)

Photo by freestocks on Unsplash