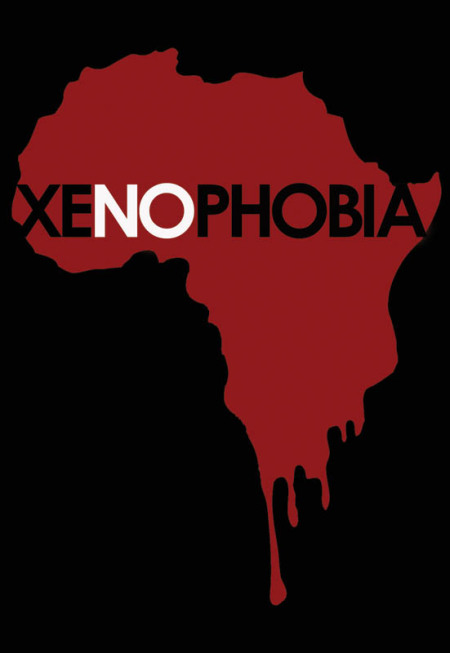

On the evening of May 12, 2008, armed with machetes and clubs, neighbor turned against neighbor in Johannesburg’s Alexandra township. Gangs of young men raped and murdered black foreigners. Their belongings were looted and scattered in the streets. During these pogroms, local disdain for the makwerekwere, the foreigners, was clear. What began in Alexandra township quickly spread. It would be marked in South African history as the May 2008 xenophobic protests, a shocking surge of violence in a nation known for its embrace of peace and diversity following decades of strife. Over 2000 Zimbabweans locked and barricaded the doors of Johannesburg’s Central Methodist Church against the gangs. Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuavhe, a Mozambican man, was beaten, stabbed and burned alive in East Rand. Images of bystanders laughing at the flickering flames circulated on cell phones, newspapers and television screens around the world. Far from a unique episode, May 2008 marked the acceleration of a growing trend of xenophobia among the South African public. These events speak to a simmering volatility in South Africa’s social fabric that threatens the post-apartheid promise of peace

This rise in violence may be explained by the twin phenomena of rampant inequality and an influx of outsiders from other African nations seeking asylum or employment. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM)[1], South Africa hosts the second-highest number of migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa, with 67.1% of migrants in South Africa originating from other South African Development Community (SADC) countries. Zimbabweans constitute a large — and ever-growing — proportion of this immigrant population. Since 2005, an estimated one million to 1.5 million Zimbabweans, many of them undocumented, have fled across the border into South Africa, the region’s economic power. In a country of 52 million people, 1.5 million immigrants cannot go unnoticed. As a result, Zimbabweans, in particular, are the recipients of a great deal of scrutiny and discrimination.

Although South Africa’s constitution is famously built on a foundation of universality, the lofty principle does not extend to the nation’s undocumented Zimbabwean migrants, a vital part of the nation’s informal economy. Whether coming from the state or the citizen, xenophobia towards Zimbabwean migrants is rooted in a legacy of exclusionary citizenship originating in the apartheid era and in the African National Congress (ANC) policy of quiet diplomacy[2] towards Zimbabwe. South Africa’s treatment of the country’s Zimbabwean population suggests that the national mantra of the “rainbow nation” may be no more than a popular myth.

The days of apartheid in which black Africans were treated as strangers in their own homeland are gone. In its place, the Republic of South Africa now stands as a “society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights.”[3] The determination to exclude Zimbabweans and other migrants from the South African national project contradicts the inclusivity that lies at the heart of the South African Constitution. After decades of oppression, the document represented more than political freedom. It was a decisive break from the past ¾ a commitment to a democratic, universalist, caring and aspirational egalitarian ethos.[4] Throughout the Bill of Rights, the subject of most clauses begins with “everyone.” As Albertyn (2008) suggests, “everyone” may properly be seen as an inclusive term meant to extend beyond citizens because of the fact that citizens are specifically accorded political rights such as the right to vote or run for political office. “Everyone” is entitled to other rights such as the right to equality, dignity, expression and critical socioeconomic rights such as the right to housing, health care, food and water.[5]

The threads of xenophobia that run throughout South Africa’s popular discourse reflect the large urban poor population’s attempts to make sense of the post-apartheid state’s failures. Despite the government’s lofty promises to guarantee socioeconomic rights such as access to food, water and healthcare, the percentage of South Africans classified as poor has remained virtually unchanged from 1994 to 2013, rising from 45.6% to 47%.[6] Because of the perception that migrants strain the already limited resource-providing capacity of the state, they become an easy scapegoat for the frustrations stemming from deferred dreams.

Disheartened by the trials of poverty, black South Africans betray their foreign neighbors in acts of violence. A 2006 national survey conducted by the Southern African Migration Project found that 84% of South Africans believed that the country was admitting too many foreigners, with many of those polled supporting measures to get rid of the foreigners. The same survey also found that average xenophobia scores were highest in the lowest income categories and generally declined with increasing income.[7] Based on this data, one might conclude the xenophobia levels are high among poor black South Africans. Furthermore, Gradin (2014) finds that there is an ethnic gap in the poverty levels among different black ethnicities: higher levels of poverty are found among the Xhosa and Zulu.[8] These findings are particularly notable because the Zulu have become increasingly associated with xenophobic attacks in South Africa in recent years. At a recent gathering in March 2015, King Goodwill Zwelithini, the leader of the Zulu nation, urged “all foreigners to pack their bags and leave.”[9] It is not surprising, then, that confronted with this inequality twenty years after the end of apartheid, according to Adjai and Lazaridis (2013), “xenophobia therefore becomes an expression of disillusionment of the government’s ability to deliver, and the ‘other’ becomes the target of frustrations.”[10]

As global attention to South Africa’s rising trend of xenophobia grows, the nation’s status as the poster child of democracy and human rights is under threat. Now, the ANC-led government faces pressure to show that the moniker “rainbow nation” is not a sham. It is ironic that the same leadership that fought against xenophobia during the apartheid era has tolerated ongoing discrimination.

At the domestic level, while the government has condemned the xenophobic violence that has taken place, declarations remain distinct from concerted action to change community attitudes. ANC officials may express solidarity with the displaced and publicly oppose the violence, but direct attempts to restrain such behavior are few and far between. As the gangs roamed the streets of Alexandra during May 2008, many of them sang popular Zulu protest song “Umshini wam” (“Bring me my machine”) as they swung their machetes. Despite the song’s violent lyrics, President Zuma supporters, including members of the ANC Youth League, often sing it at rallies.[11] Glasser (2008) notes that “in some quarters Zulu-ness seems to have become a standard of South African-ness, with those unversed in Zulu vocabulary liable to be attacked as un-South African.”[12] During the attacks, South Africans under suspicion of being foreigners were subjected to an “elbow test” in which potential victims were asked to say the Zulu word for elbow, indololwane.[13] The practice bears an eerie resemblance to the pencil tests of the apartheid era when racial classification was dependent on whether a pencil slid in and out of one’s hair. If it got stuck due to the coarseness of hair, one was black. If it slid out, one was white. Two decades into South African democracy, “it appears some South Africans are using similar degrading methods to oppress and violate fellow Africans.”[14] Xenophobia is a pressing issue among Jacob Zuma’s large Zulu consistency, a group that has played a unique role in instigating xenophobic discourses and attacks. Although President Zuma has not bowed to populism by endorsing xenophobia, he does not demonstrate strong leadership through his silence within the Zulu community.

Perhaps given decades of oppression under minority rule, such slow progress is understandable. While in the past, political elites may have been complicit in violence against towards Zimbabweans through foreign policy choices and a dearth of leadership, in 2010, the government took a step forward by introducing special dispensation permits for Zimbabwean nationals. In 2009, the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) announced a moratorium on deportations to allow Zimbabweans illegally in South Africa to obtain appropriate documents (e.g, visas, asylum-seeking documents) to stay in the country. In 2010, the special dispensation allowed Zimbabweans formally employed or studying prior to May 2010 to apply for and obtain work or study permits.[15] While this dispensation regularizes only a small portion of the estimated 1.5 million Zimbabweans in South Africa, it is a step forward in transforming a cultural of inclusion from paper to practice.

The South African government’s tacit endorsement of anti-immigrant protests, however, in February 2017 suggests that progress in reducing xenophonic sentiment among South Africans will follow an arc rather than a straight path. In the face of violence and hate speech, Zuma characterized protests as “anti-crime” rather than “anti-foreigner.” Government obscuration of the ethnic dimensions of attacks and abuse of foreigners led the Nelson Mandela Foundation to condemn the Zuma administration as “giving permission for a march of hatred.”[16] The periodic rise of xenophobia in South Africa not only damages the nation’s image of tolerance, but also highlights its government’s inabilities to foster economic growth and social cohesion. The promise of the “rainbow nation” can only be fulfilled when the state first rectifies the inequality of the apartheid era.

When Archbishop Desmond Tutu chaired South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he popularized the philosophy of Ubuntu that is especially relevant in light of the nation’s struggles with xenophobia. While difficult to express in most Western languages, the spirit behind the word may be summarized in Xhosa. The phrase “Umntu ngumntu ngabanye abantu [may be] understood in English as ‘People are people through other people” and “I am human because I belong to the human community and I view and treat others accordingly.’”[17] In the South African context, Ubuntu is a rallying call to prioritize a broad vision of humanity. South Africa is a nation built on diversity. Its people may be united by a history of violence, but they are also united by a history in which migrants have helped shaped the country’s economic fortunes.

References:

[1] Céline Mazars et al., The Well-Being of Economic Migrants in South Africa: Health, Gender and Development (Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration, 2013), 9, accessed March 19, 2015, http://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/What-We-Do/wmr2013/en/Working-Paper_SouthAfrica.pdf

[2] In this essay, I use the term “quiet diplomacy “ to refer to a diplomatic style that shies away from critical public and media scrutiny in favor of “quiet” policy measures behind closed doors.

[3] Republic of South Africa, “Constitution of the Republic,” South Africa Government

[4] Cathi Albertyn, “Beyond Citizenship: Human Rights and Democracy,” in Go Home Or Die Here: Violence, Xenophobia and the Reinvention of Difference in South Africa, ed. Shireen Hassim Hassim, Tawana Kupe Kupe, and Eric Worby (Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press, 2008), 178.

[5] Albertyn, “Beyond Citizenship: Human Rights,” in Go Home Or Die Here, 176.

[6] Haroon Bhorat, “Economic Inequality Is a Major Obstacle to Growth in South Africa,” New York Times, December 6, 2013, accessed March 28, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/07/28/the-future-of-south-africa/economic-inequality-is-a-major-obstacle-to-growth-in-south-africa

[7] Jonathan Crush, The Perfect Storm: The Realities of Xenophobia in Contemporary South Africa, Migration Policy Series 50 (2008), accessed April 9, 2015, http://www.queensu.ca/samp/sampresources/samppublications/policyseries/policy50.htm

[8] Carlos Gradin, Poverty and ethnicity among black South Africans (United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, 2014), accessed April 12, 2015, http://www.wider.unu.edu/publications/working-papers/2014/en_GB/wp2014-113/.

[9] S’thembiso Msomi, “King Goodwill Zwelithini speaks the language of Cecil John Rhodes,” Rand Mail Daily (South Africa), March 25, 2015, accessed April 9, 2015, http://www.rdm.co.za/politics/2015/03/25/king-goodwill-zwelithini-speaks-the-language-of-cecil-john-rhodes. See page 23 for more details of Zulu complicity in South African xenophobia.

[10] Carol Adjai and Gabriella Lazaridis, “Migration, Xenophobia and New Racism in Post-Apartheid South Africa,” International Journal of Social Science Studies 1, no. 1 (April 2013): 194, accessed March 19, 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v1i1.102

[11] “Zuma: If ANC goes down, so will SA,” Namibian Sun (Windhoek, Namibia), November 28, 2014, accessed March 28, 2015, http://www.namibiansun.com/international/zuma-if-anc-goes-down-so-will-sa.74038

[12] Daryl Glaser, “(Dis) Connections: Elite and Popular ‘Common Sense’ on the Matter of ‘Foreigners,'” in Go Home or Die Here: Violence, Xenophobia and the Reinvention of Difference in South Africa, ed. Shirley Hassim, Tawana Kupe, and Eric Worby (Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press, 2008), 58.

[13] Kerry Chance, “‘Broke-on-Broke Violence,'” Slate, accessed March 28, 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/foreigners/2008/06/brokeonbroke_violence.html

[14] Nosimilo Ndolovu, “The 21-st century pencil test,” Mail & Guardian (Johannesburg, South Africa), May 24, 2008, accessed March 28, 2015, http://mg.co.za/article/2008-05-24-the-21st-century-pencil-test

[15] Médecins Sans Frontières, Nowhere Else to Go (2011), accessed April 11, 2015, https://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/nowhereelsetogo.pdf

[16] “Media Statement: Nelson Mandela Foundation Calls out the Growing Behaviour of ‘othering’ among Africans.” Nelson Mandela Foundation, 24 Feb. 2017), accessed March 8, 2017.

[17] Kevin Chaplin, “The Ubuntu spirit in African communities,” accessed April 9, 2015, htt://www.coe.int/t/dg4/cultureheritage/culture/Cities/Publication/BookCoE20-Chaplin.pdf.