BY ANISH TIWARI

On the brisk morning of August 15, 2015, as India celebrated its 69th Independence Day, prime minister Modi introduced “Start-up India, Stand-up India,” to the country for the first time. Five months later, Modi officially launched the initiative amidst much fanfare, with a vision of creating a supportive ecosystem for entrepreneurs and transforming India into a land of job creators instead of job seekers. In January 2019 startup India celebrated its third anniversary and, ironically enough, in May 2019 ministry of statistics released a report confirming an unemployment rate of 6.1% in India for the 2018 fiscal year, the highest recorded in 45 years.

Despite this high unemployment rate, Startup India, unlike other initiatives of the Modi government, remains under-scrutinized, failing to garner any notable media attention, even during the 2019 general elections campaign trail. The historic return of Mr. Modi for the second term to the prime minister’s office, along with the historic rate of unemployment, calls for a long-pending, academic analysis of the Startup India initiative. It is impractical and unfair to expect Startup India to fully resolve unemployment in the country in such a short span of time, as entrepreneurship policies take several years to come to fruition. However, it is important to address the policy’s structural flaws which are hampering its effectiveness, namely the lack of gender balance, overemphasis on the high-tech sector and lack of availability of seed-stage funding.

Lack of Gender Balance

Encouraging female entrepreneurship can be a force for economic growth and development. However, due to the deep-rooted patriarchal mindset of many of today’s societies, entrepreneurship has largely been a male-dominated enterprise. This has led to the marginalization of female entrepreneurs. India, sadly, is no exception to this trend, and the Startup India initiative fails to address this gender disparity. Female entrepreneurs account for just 9% of the total entrepreneurial population of the country. India ranked 48th of the 57 examined countries, the lowest in the BRICS[1] nations and the Asia-pacific region, according to the 2018 Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs. This dismal performance testifies to a missed opportunity as equal participation of women could add up to $770 billion to the Indian GDP by 2025. Encouraging female entrepreneurship is not merely a social argument anymore, but an economic argument instead. Though 35% of the directors of DPIIT[2] recognised startups under Startup India programme in 2018 were women, the absence of the terms “female” and “women” from both the action plan of 2016 and status report of 2018 raise serious questions on the intention of policymakers to advance the cause of female entrepreneurship in India. Furthermore, it also doesn’t fit with Modi’s popular political narrative of “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” which effectively translates to safeguarding and educating the girls. Finally, despite promising a collateral-free credit scheme of up to ₹50 lakhs ($71,785) with preferential lending to women entrepreneurs in the election manifesto of 2019, the Modi government hasn’t officially announced the plan yet.

Source: MIWE, 2018

Overemphasis on High-tech Sector

The emphasis of Startup India on high-tech enterprises can be ascertained from the fact that the word “innovation” and “technology” is mentioned 46 and 31 times, respectively in the 40-page long Startup India action plan. Although the high-technology sector may seem like an obvious place to look for employment-generating high-growth firms, such overemphasis fails to acknowledge opportunities in the other sectors. Research suggests that high-growth firms exist across all sectors. Indian unicorns, in general, represent a variety of sectors and industries including e-commerce, food-tech, ed-tech, fin-tech, hospitality, and logistics. For instance “Flipkart,” the poster child of India’s startup ecosystem, which made headlines after being acquired by Walmart Inc. for a whopping $16 billion, was an online retailing company. Another key characteristic of Startup India is its focus on encouraging university spin-offs by building innovation centers and funding R&D. While increased investment in R&D is a good strategy, R&D on its own does very little to improve the growth prospects of new firms. Support for R&D differs from support for innovation, the latter often being a result of opportunity recognition, exploitation and customer interaction. Hence, policymakers must make a clear distinction between technology policy and policy for promoting high-growth firms as they are two very different things, which cannot be substituted by one another.

Financial Hurdles

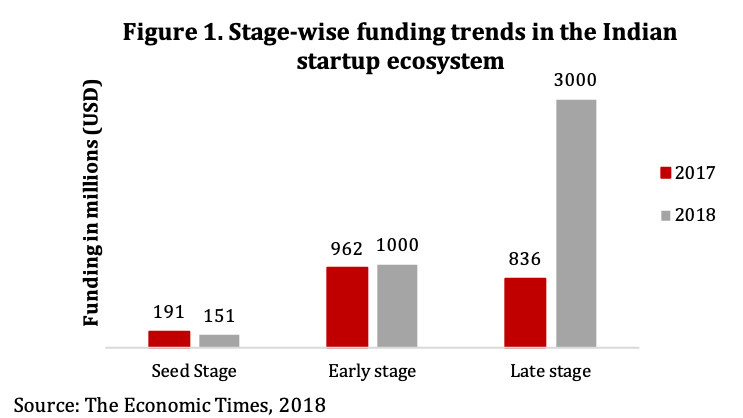

Difficulty in getting access to funding is the biggest hurdle faced by startups. 50% of Indian entrepreneurs said the lack of financial support was a major strategic constraint, with more than 38% stating it as a key reason for the closure of their ventures. Though late-stage funding in the Indian startup ecosystem has surged over the past years, seed-stage funding has declined. To cater to the financial needs of the ecosystem, a Fund of Funds for startups was created at the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) under the Startup India initiative. The government announced its total support of ₹10,000 crores ($1.4 billion) over a period of four years. However, as per the latest update by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry on June 28th, this fund has only committed ₹3,123.20 crores ($439 million) to 49 AIFs[3], out of which merely ₹483.46 crores ($68 million) has been disbursed so far. In an ecosystem where the seed-stage funding has registered a downfall, a mere 31% allocation and 4.8% disbursement of the total announced support is gravely insufficient to meet the financial needs of new startups. One of the promises made by Mr. Modi in his 2019 election campaign was to double the size of fund of funds for startups to ₹20,000 crores. However, with 95% of the existing fund remaining to be disbursed, that promise looks shaky at best.

Startup India initiative is one of the highlights of the Modi regime and a key pillar of his idea of a “New India” where innovation takes a central role. However, this crucial pillar of Modi’s “New India” is plagued by deep-rooted problems which are in fact, not very new to India. The painstakingly complex bureaucracy coupled with a society that continues to stifle the economic advancement of women and the sub-par engagement with stakeholders from academia and industry is hampering an otherwise promising initiative. Thus, policymakers must revisit and restructure Startup India to help catapult the entrepreneurial spirit of the country in the right direction.

Anish Tiwari is Marie S. Curie fellow at Dublin City University, Ireland and a member of the Global India ETN. His PhD looks at high-tech acquisitions in India and its regional economic implications. Prior, Anish was an audit associate at Deloitte Ireland. Anish holds a master’s in international business from UCD Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School.

Edited by: Margaret Kadifa

Photo by: Anish Tiwari

[1] BRICS is an informal group of states comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

[2] Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) is the nodal agency responsible for implementing Startup India. It reports to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India.

[3] Alternative Investment Funds obtain money from SIDBI and invest it downstream in selected startups.