BY ZACH MONTAGUE

Close to a decade into Beijing’s global soft power campaign, not much about the plan has worked. As devised by former President Hu Jintao back in 2007, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has invested billions annually in initiatives worldwide designed to complement China’s economic and military power with renown for its culture. Without the powerful reach of a Hollywood-size film industry, or mature institutions like the British Council or Goethe Institute, neither China’s creative arts nor its public figures have seized much global attention. Yet where most of this drive has fallen flat, one aspect has been hugely successful and still shows great promise – fostering the spread of the Chinese language.

Even without Beijing’s encouragement, the incentives for students to study Chinese are already considerable. Each year of rapid growth in China brings more prospects of jobs and higher salaries, luring foreign workers. As the most spoken language globally, dwarfing both Spanish and English by over half a billion speakers, the ability to communicate in Mandarin opens other doors as well. Chinese is anticipated to become the most-used language on the internet, if it hasn’t already, right as web giants like Alibaba and Tencent are tightening their grasp over online commerce. And though the majority of speakers are still concentrated in the mainland, knowing Chinese provides entry into other markets such as Singapore.

To top this off, the CPC has been working aggressively to court foreign students by picking up the tab on education. This year, a flagship program to bring 18,000 African students to Chinese universities on government scholarships is entering full swing. This will build upon the work of over 450 Confucius Institutes, which already fund Chinese language training at universities around the world. Although controversies over Confucius Institutes pushing a political agenda have caused several top schools to shutter their chapters, many others with tighter budgets rely on these funds to keep their Chinese departments afloat. And even amidst the public pushback from certain Western institutions, the government body that administers the Confucius Institutes (colloquially known as Hanban) has quietly been making inroads with other projects. For example, Hanban collaborated with the College Board to develop an Advanced Placement exam in “Chinese Language and Culture” which has been available since 2007.

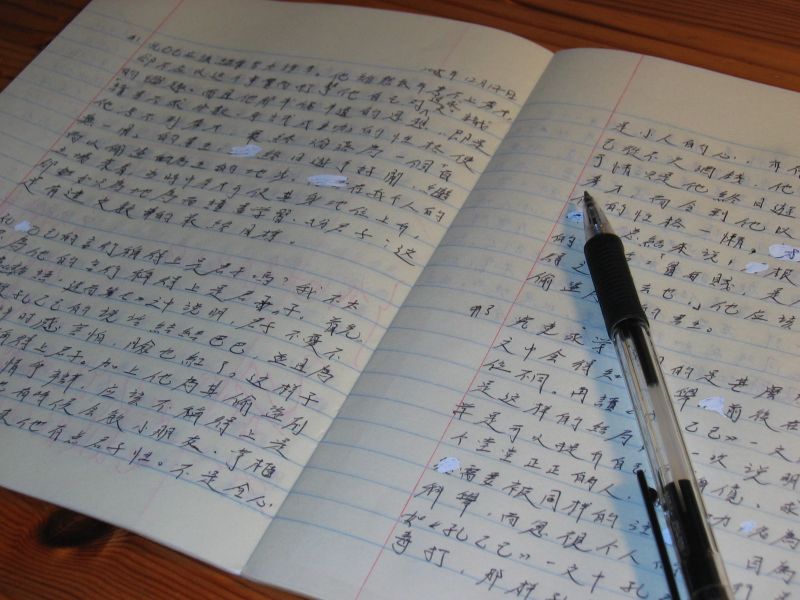

Beijing’s play to turn Chinese into an internationally coveted skill is especially necessary given the language’s complexity. Simply making the language more manageable for native speakers is a challenge that has vexed scholars and politicians for virtually all of China’s modern history. As early as the 1920s, a movement of prominent scholars such Lu Xun and Qian Xuantong sought to abolish Chinese altogether, replacing it with Esperanto. After this came the well-known campaign by Mao in the 1950s to simplify Chinese from the traditional form still used in Taiwan and Hong Kong, in order to increase literacy. And even though this simplified system has survived up through the present, leaders are still struggling to weed out vestiges from Chinese’s classical roots. Just in 2009, a government plan to retire tens of thousands of obscure characters caused an outcry from many citizens who still have these antiquated words as surnames.

So for non-native speakers, learning Chinese represents an even more daunting task. The challenge of tones in spoken Chinese is an additional hurdle, as are the various regional dialects like Cantonese or Shanghainese, which are effectively different languages. Taken together, these technical challenges present students with a steep learning curve, and to Beijing, this impacts China’s influence in world affairs.

Building a linguistic bridge to the rest of world has obvious advantages. On a practical level, it encourages tourism, facilitates business, and aids information flow in important mediums like academic journals. In a less measurable way, it also builds a sense of approachability that attracts foreign talent, and burnishes national image. China’s language barrier with most of the world is therefore problematic, especially with suspicion about China on the rise in much of Asia. So to more fully reap these benefits, Beijing is pushing Chinese as a global language, and this requires investment.

By every indication, however, Beijing’s investments are already paying off. According to survey data from the Asia Society, the number of US public schools offering Chinese grew by over 200% between 2004 and 2008. Despite extraordinary setbacks, the Pakistani government is staying the course on a 2011 plan to make Chinese mandatory for all students after grade six. And even in Indonesia, where ethnic strife caused a general suppression of Chinese education for decades, the language is making a huge resurgence across top universities.

As long as China’s economy continues to grow, financial incentives will be enough to entice some students to dive in and pick up the language. But this is a far cry from linguistic integration with the rest of the world. Before there can be an overseas market for Chinese pop music or a significant American presence on Weibo, for example, there must be a higher interest in learning Chinese generally. While its methods haven’t always been subtle or smooth, Beijing is laying the groundwork to build this level of interest. If its ambitions to become a global superpower are to succeed, however, it will need to continue, as well as introduce new, more creative tactics.

The brute force of government-funded education programs may be effective in circles where money is scarce. But Beijing cannot continue to brazen it out while prominent Western institutions shun its Confucius Institutes and other efforts. Ideally, recent progress will give the Chinese government room to step back and rely on more organic methods of exporting its language, such as pressure from the massive Chinese diaspora in North America and Southeast Asia. Just as the New York Times’ decision to offer a Mandarin version reflects the size and influence of that audience, the integration of more Chinese into American and Canadian society will naturally foster demand for Chinese education and bilingual media. Beijing would be wise to capitalize on this momentum and find ways to quietly increase the language’s prominence in the West.

Zach Montague is a New York-based researcher and political analyst. He focuses on Asia and China’s transformative role in the region, and has previously worked out of Xi’an and Beijing.

Photo by Simon Shek on Flickr