This piece was published in the 31st print volume of the Asian American Policy Review.

This experience reaffirmed the importance of a bottom-up approach to policy formation; we need to collect data on the issues which communities face to find emerging trends, and we need to ask the affected communities what changes they want.

“We have all seen, at the same time that the coronavirus pandemic has broken out, so, too, has a disturbing epidemic of hate and discrimination against the AAPI community, and that has erupted.

According to the Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center, more than 2,500 recorded incidents of anti-Asian hate have been perpetrated against AAPI communities . . . Many of these incidents represent civil rights violations. And that is a value for us to protect.”

—House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi

In her floor speech on a House resolution, Speaker Pelosi acknowledged the pervasive upsurge in anti-Asian hate during the Coronavirus pandemic. Citing numbers from Stop AAPI Hate (SAH), a coalition of civil rights organizations and SF State University Asian American studies, she highlighted “the systemic injustices and discriminations perpetrated against generations of Asian Americans” and noted that “some of the bigotry is being fueled by some in Washington DC.”[i]

From its inception in March 2020, one of SAH’s objectives was to shape the narrative about anti-Asian hate.[ii] Rather than framing COVID-19 discrimination as isolated incidents by a few prejudiced individuals, the coalition wanted to 1) connect it to historic racism against Asian Americans; 2) articulate the widespread, systemic nature of this racism; and 3) promote solidarity with other communities of color. As Speaker Pelosi’s speech and the LA Times op-ed “Anti-Asian Hate Crimes Are Surging. Trump is To Blame” attest, SAH succeeded in putting this issue on the agenda of policy makers and in pinning racism on the officials’ political rhetoric.[iii]

Along with raising awareness about COVID-19 discrimination, SAH sought to develop policies that addressed the roots and trends of the problem. Their data analysis revealed that most incidents were not hate crimes, but primarily cases of harassment and shunning. Consequently, in formulating policy solutions SAH prioritized models of public education, restorative justice, and civil rights enforcement over hate crime enforcement.

San Francisco State University students in Asian American Studies (AAS) were instrumental in setting anti-Asian racism on political leaders’ agenda, formulating policies, and advocating for them. This case study of our involvement with SAH first describes the activities of SAH. It then reviews how we were engaged with the policy process and what we learned as we 1) reviewed data; 2) produced policy reports; and 3) advocated for specific recommendations. To conclude, we share lessons for other community-based, participatory research efforts oriented towards effecting social change through public policy.

Stop AAPI Hate: Tracking Anti-Asian Hate during COVID-19

When news of the COVID-19 epidemic in China broke in January 2020, Dr. Russell Jeung of San Francisco State University AAS knew that it would lead to the scapegoating of the Chinese, and to subsequent racism against Asian Americans both in terms of interpersonal violence and nativist government policies. Along with graduate researchers Sarah Gowing and Kara Takasaki, he began to document news accounts of anti-Asian hate and reported on the upsurge of incidents of shunning, harassment, and boycotts of Asian businesses.

Having documented the increasing extent of this racism through secondary sources, he joined with two community organizations—Chinese for Affirmative Action in San Francisco and the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council of Los Angeles—to call upon the California Attorney General to create a reporting center for COVID-19 discrimination. When that office responded that it lacked the capacity to do so, Dr. Jeung and his collaborators launched Stop Asian American Pacific Islander Hate (SAH) to gather first-hand accounts of hate incidents. Receiving support from the CA Asian Pacific Islander Legislative Caucus and garnering extensive media attention, the tracking center received hundreds of reports daily in the first three weeks.

SAH has since become the leading advocacy organization and thought leader in combating anti-Asian hate during the pandemic. SAH’s research and advocacy with elected leaders have led to:

- President Joe Biden’s memorandum “Condemning and Combating Racism Against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders”

- A US congressional resolution denouncing anti-Asian hate

- Over three dozen local resolutions calling for tolerance and respect

- The formation of city task forces in New York and San Francisco

- Pronouncements from CA Governor Newsom and CA Superintendent of Schools Tony Thurmond resisting racism and bullying

- A forum with the CA Assembly on the State of Hate

- A convening of staff from Human Relations Commissions nationwide on best practices to address anti-Asian hate

- Having issued fourteen reports in 2020 on hate incidents, anti-Chinese rhetoric, and state-specific trends, SAH also received widespread media attention. The New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, NPR, and Time Magazine, as well as international and local media, have featured SAH’s work.[iv]

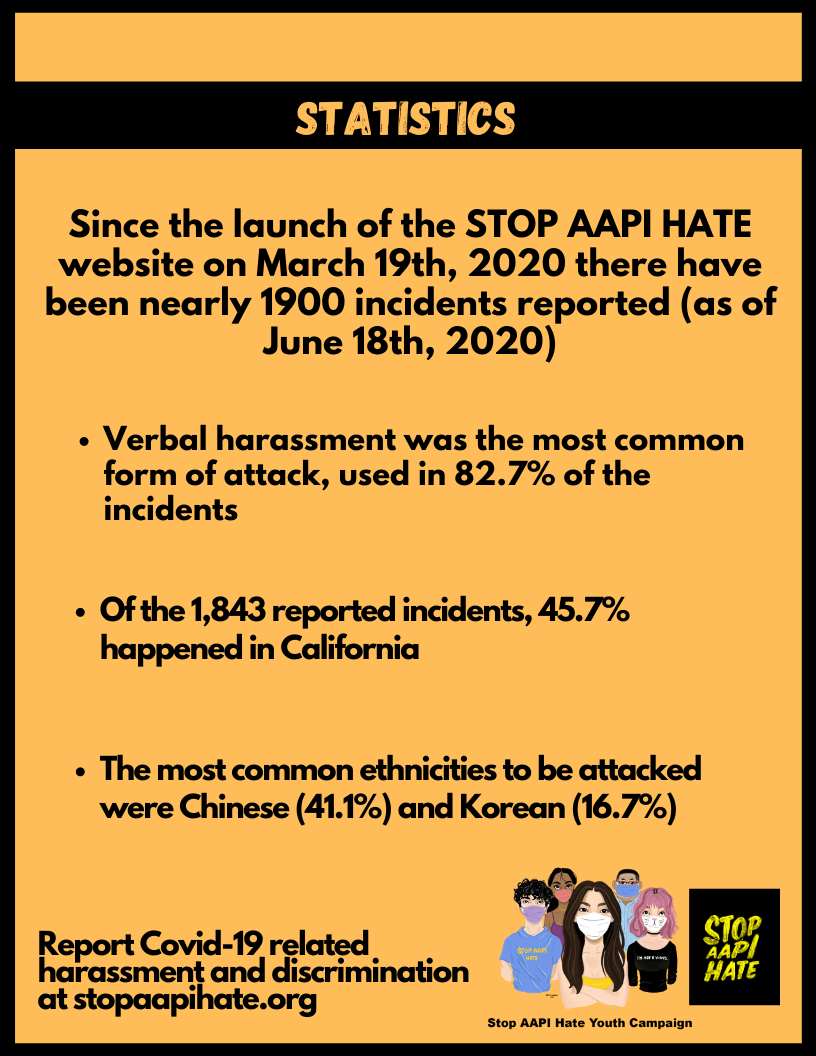

Along with its data reporting and advocacy, SAH established a national Youth Campaign to raise awareness about the issues of racism faced by young AAPIs. Led by twelve young adult team leaders, the campaign’s ninety high school interns developed a social media campaign, gathered 930 interviews of peers, created educational workshops, and wrote their own policy report, “They Blamed Me Because I Was Asian.”[v] They continue to advocate for their youth policy recommendations and to lead their workshops for other young adults.

The activities of SAH follow the first three stages of the public policy process: agenda-setting, policy formation and policy advocacy.[vi] Conducting community-based, participatory research from an Ethnic Studies paradigm,[vii] this project aimed to uplift the voices of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, develop a collective voice, provide community resources, offer technical assistance, and develop policy recommendations.[viii]

The following lessons learned by San Francisco State University AAS graduate students demonstrate both this methodology and paradigm. Richard Lim discusses how categorizing the language employed by perpetrators of hate demonstrated the racial bias of their acts and put anti-Asian racism on the agenda of policy makers. Working with high school interns, Krysty Shen highlights how SAH utilized social media to reach out to youth and employed qualitative story gathering to ascertain the issues facing youth. They then formulated appropriate policy recommendations for their concerns, such as online harassment. Similarly, Megan De la Cruz shares how student interns researched best practices to address racism in schools and integrated their perspectives to create key recommendations. Finally, Boaz Tang describes how he worked with SAH to tailor its priorities for California Governor Newsom’s office and to marshal the efforts of state agencies in addressing COVID-19 discrimination.

Documenting Bias and Setting anti-Asian Hate on the Agenda (Richard Lim)

789 incidents.

Each incident included some vitriolic comment against Asian Americans. Some statements vocalized hostility: “Cover your f**king mouth, you Chinese b***h! How dare you yawn at me!” Others made threats on Asian American lives: “If you are Chinese or Japanese, I’m going to kill you!” Reading incident after incident left me with anxiety. And negotiating my angst while coding data became increasingly challenging. Despite my frustration, I channeled my energy to categorize the cases we received. We wanted to publish both Asian American lived experiences and the alarming trends facing them to demonstrate the significance of anti-Asian hate to policy makers and the general public. I argue that our reports amplified this issue even amidst the pandemic, the George Floyd killing, and the presidential election. Media reporting on our work expanded awareness and placed further pressure on policy makers.

To begin, the primary accounts of hate incidents provided an entry point to understanding COVID-19 discrimination. Recording isolated, individual incidents was not the primary goal of SAH. Instead, we aimed to tie hate speech to reported incidents and thus reveal how the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype harms Asian Americans. Highlighting perpetrators’ comments indeed proved critical in demonstrating the nativist and Sinophobic natures of these incidents.

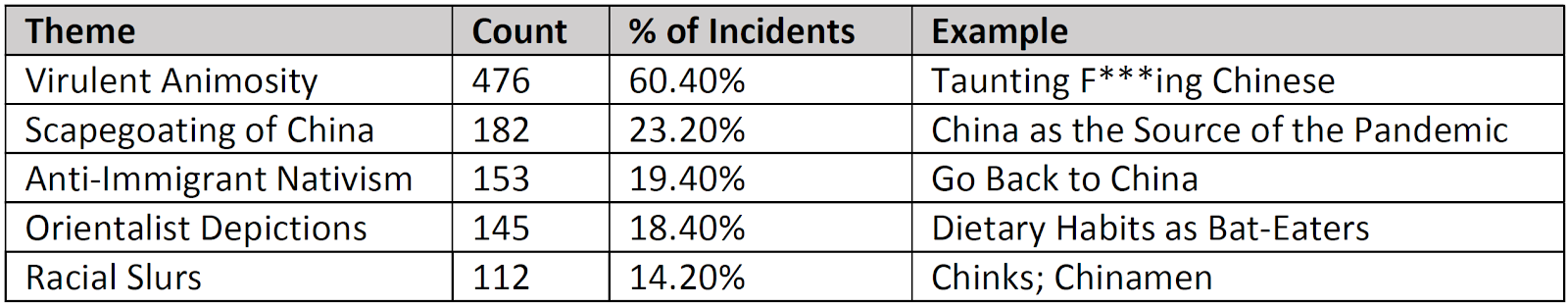

To verify the nationwide severity of anti-Asian hate incidents, my research team and I categorized incidents based on the statements employed by perpetrators as reported by respondents to SAH. Further coding and analysis yielded five major themes in how perpetrators of hate harangued Asian Americans: 1) virulent animosity; 2) Chinese and China related scapegoating; 3) anti-immigrant nativism; 4) Orientalist depictions; and 5) racial slurs. Certain vocabulary often distinguished one comment’s themes from another. For example, while the theme “virulent animosity” often constituted expletives, “Chinese and China related scapegoating” comments involved some reference to blaming Chinese people as the source of the coronavirus. Comments of “anti-immigrant nativism” involved the perpetrator complaining that Chinese people should “go back to China.” Incidents with “Orientalist depictions” revolved around statements about Asians’ cultural exoticism, such as their dietary habits. Finally, cases involving “racial slurs” referenced derogatory Asian labels, such as Chink, Gook and Chinaman.

Just by bearing certain physical features, I found myself linked with fellow Asians and also felt scapegoated as a vector of death. In particular, the high number of “Go back to your country!” comments dumbfounded me for being so nativist. And given the anti-China rhetoric coming from the president and the Republican Party during the pandemic, Orientalist depictions of Asians as “diseased” and subversive troubled me. Our data offered a reminder that regardless of our citizenship, Asian Americans continue to be seen as conditional Americans.

By documenting anti-Asian hate incidents, we provided the media with the necessary evidence to underscore the racial motivations behind the acts of hate. Bold headlines from media outlets such as Vox declared, “How the Coronavirus is Surfacing America’s Deep-Seated Anti-Asian Biases.”[ix] Such articles employed SAH’s framing to highlight how the racism during the coronavirus pandemic was no aberration.

Ultimately, the media accounts, in conjunction with advocacy of Asian American groups, catalyzed responses from politicians. In a Huffington Post article titled “Trump Is The Biggest ‘Superspreader’ Of Anti-Asian Racism,” Connie Chan, a candidate for San Francisco supervisor, also reinforced that the discrimination she faced was a product of Trump’s anti-China rhetoric.[x] At the federal level, Democratic US Senators Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren and Tammy Duckworth sent a letter to the U.S Commission on Civil Rights, where they urged a government response to increasing anti-Asian hate.[xi] Later, Congresswoman Judy Chu and members of the Congressional Asian, Latino, and Black caucus pushed a resolution calling for action against growing anti-Asian hate, with the resolution citing SAH’s numbers.[xii] As media and elected leaders responded to SAH’s reports and prioritized anti-Asian, AAPI youth took the next step to identify policies to address the issue.

Social Media and Story Gathering: Policy Formulation for AAPI Youth Issues (Krysty Shen)

On June 1, 2020, Dr. Jeung asked SAH volunteers about piloting a summer youth internship. I expressed interest, and four days later we held our first planning meeting. The next day we distributed our flyers on social media, and within a week we received over 100 applications and hired twelve team coordinators. Within only two weeks, we officially launched the SAH Youth Campaign.

This short timeline shows how quickly we were able to mobilize and start an on-going, national Youth Campaign. Eventually, the youth interns themselves have built a social movement as a virtual community. Social media work, and later interpersonal story gathering, were critical for our Youth Campaign; they served as the basis for formulating specific policies to address the hate issues that AAPI youth face.

The youth-requested and youth-led SAH social media campaign suggests the growing importance of utilizing an online platform for youth organizing and highlights their adeptness with online information distribution. Compared to community-based organizing in the past, newer generations are no longer bound to their immediate, proximate networks. In their applications, the great majority of youth wrote that the best strategy to get youth to report to SAH was through social media outreach. We incorporated their input and included a Social Media Campaign as the first unit of the internship.

SAH youth interns created a wealth of resources for their online networks. In under two weeks, my intern team developed a multi-slide educational resource with a historical timeline of anti-Asian hate, statistics and quotes from SAH, and a call to action to report incidents to post on Instagram. Continuing interns recently launched an Instagram account and will publish materials from the summer campaign. Their passion and speed in producing content demonstrated their adeptness with media technology and in connecting with their peers.

The second unit for our internship was the Stories Campaign. We wanted youth to practice holding difficult conversations with peers in order to gather what was happening in their settings. While youth interns were well-versed with social media, they were less skilled at direct, verbal communication. Several interns asked if they could hold text conversations as a substitution, but we emphasized the interpersonal connections of phone calls and/or video calls. These direct interactions were crucial to gathering and gaining deeper understandings of the personal accounts of anti-Asian hate that youth experienced. From the youth interviews, one-fourth of peer respondents experienced COVID-19 discrimination first-hand. Interns noted a trend that many of these incidents occurred online. Aside from the Youth Campaign, I was also working on a separate policy report on youth incidents for SAH, and I had not realized the prevalence of online incidents prior to youth bringing it to the forefront.

Because of youth efforts in gathering stories and documenting cyber-bullying, we integrated an emphasis on online incidents to both the Youth Campaign and adult version of the youth policy report. This experience reaffirmed the importance of a bottom-up approach to policy formation; we need to collect data on the issues which communities face to find emerging trends, and we need to ask the affected communities what changes they want. Armed with this data, the youth interns then researched evidence-based best practices to deal with anti-Asian hate directed at youth.

Formulating Youth Policy, Part 2: Tailoring Youth-led Policies (Megan Dela Cruz)

“The gathering of stories allowed us to integrate the issues of AAPI intersectionality to the Youth Campaign policy report in a much stronger way.”

– V. S., SAH Intern (17 y. o.)

After gathering 930 stories from their peers, the interns focused on a policy report with recommendations that address anti-Asian racism at the school level. This report would be the culmination of the interns’ experience and showcase what they had learned through the Social Media Campaign, the Stories Campaign, and the workshops facilitated by the program leaders. The students synthesized the data gathered through the Stories Campaign, as V. S. notes in the above quotation, and included their own points of view in creating effective remedies for school-based and online bullying.

The interns developed the following policy recommendations:

- Implement Ethnic Studies throughout secondary school curricula to center histories of communities of color, analyze the sources of systemic racism, and learn from movements that advocate for equity for people of color.

- Provide anti-bullying training for teachers and administrators that would include practices of social-emotional learning.

- Train students and adults in restorative justice practices, which can begin to replace zero tolerance approaches that have proven ineffective.

- For online harassment and bullying, provide accessible and anonymous reporting sites on social media platforms.

- Support AAPI student affinity groups and their school-safety and anti-racism campaigns.

About forty-five interns worked on this policy report—gathering data, choosing images, and crafting a document for school districts. By working on the policy report, I was able to learn about policy formation and advocacy at the local level. In particular, I assisted the interns in developing policies particularly suited for local school contexts that vary in size and demographic composition.

The first section of the policy report included the history of anti-Asian racism and the current context of COVID-19 discrimination. The curriculum from the Youth Campaign helped interns interpret the current political moment during the 2020 elections, especially the rhetoric from elected officials inflaming xenophobia and giving license to hate. The interns also explored the economic conditions and Yellow Peril stereotype that have also given rise to hostile treatment of AAPIs.

The second section of the report analyzed the data from the Stories Campaign. The interns reviewed both quantitative and qualitative data to understand the extent and nature of anti-Asian bullying. They found that cyberbullying in the form of hateful comments and racist videos was quite prevalent, such that it seemed to be normalized behavior not often deemed as racism.

Students thus wanted to address bullying of Asian Americans at their high schools, specifically centering bullying as racialized microaggressions. The interns investigated policies that address the sources of the problem, as well as build on the strengths of our ethnic communities. To get at the root of racism, the interns found that Ethnic Studies and high school affinity groups were effective in promoting solidarity and coalitions. They realized that by learning their own histories and by organizing their fellow students, they could find power as they mobilized affinity groups. In order to deal with bullies, they recommended restorative justice models as better than zero tolerance policies that led to inequitable suspension rates. And to support Asian American students targeted with racism, they highlighted the need for mental health resources based in schools. Each of these recommendations included citations of the research that documented their efficacy and feasibility.

Finally, given the interns’ focus on effecting change at the school and school district level, the report offered policy recommendations by researching best practices that were applied to their own experiences. They acknowledged that different school contexts based on district size and school demographic composition led to varied levels of power and influence that the students could exert. They therefore provided general recommendations that could be tailored to different schools and prioritized according to school need.

Although the summer portion of this internship has ended, some high school interns have decided to continue their work and implement their recommendations. In fall 2020, interns hosted a nation-wide conference to spread awareness of the issue and build a student movement for social change. Largely influenced by the recommendations of the report, the interns are advocating plans to implement Ethnic Studies within their school districts.

Overall, the Youth Campaign and their policy report are models of community-based participatory research conducted by high school interns. Through social media and Zoom meetings, they were able to meet nationwide and to develop a social media campaign to raise youth concern for this issue. By gathering stories and documenting youth experiences, the interns verified the ongoing surge of racism targeting Asian American high school students.[xiii] And through integrating best practices with their own experiences and knowledge, they have developed a policy platform aimed at empowering, healing, and transforming their communities. Having developed policy recommendations, the next step for SAH was to advocate for their implementation.

Promoting Policies Given Political Contingencies: Policy Advocacy at the State Level (Boaz Tang)

“One thing I also want to express is deep, deep recognition of the xenophobia, racism that is being perpetuated against Asians in our state. We have seen a huge increase in people that are assaulting people on the basis of the way they look and I just want folks to know we are better than that, we are watching that, we’re going to begin to enforce that more aggressively . . .[xiv]”

–Governor Gavin Newsom (CA), March 19, 2020

I felt stunned to hear a public official denounce anti-Asian discrimination and violence at a press conference. Having been gutted by the long legacy of vitriol towards the Asian American community, I was stirred with pride over finally being seen by the governor. One month later, Professor Russell Jeung reached out to me and a handful of other San Francisco State University graduate students to join the SAH research team. At the time, I did not realize that SAH’s research and advocacy were the catalysts for Governor Newsom’s remarks, and I certainly did not anticipate researching policy recommendations for a meeting with his key staff just a few weeks later. I had to help frame the aims of SAH—to promote public education and restorative justice models—according to the concerns, scope, and limits of the governor’s office.

SAH’s policy recommendations address systemic racism through public education and restorative justice measures, in contrast to previous models of hate crime enforcement. From our research, we found that Ethnic Studies[xv] and particular types of anti-racism education[xvi] were effective in curbing the xenophobia towards Asian Americans. In addition, the George Floyd killing in June 2020 and the Black Lives Matter movement made us well aware of the failures of our criminal justice system that were largely retributive and punitive. Instead, SAH saw restorative justice as an essential part of ending structural racism leveled at communities of color. Indeed, such measures are effective in increasing community resilience, lowering recidivism rate, and decreasing financial costs for all parties in conflict.[xvii] Thus, we prioritized these policy approaches for their philosophy and efficacy.

Given the agencies that the governor’s office oversaw, we tailored our recommendations for state departments that handled sites where we tracked anti-Asian incidents. According to our research, 38 percent of California hate incidents occurred at businesses. Our recommendation to the governor’s office was for the Department of Fair Employment and Housing (DFEH) to better promote and enforce public accommodations, as protected by the Unruh and Ralph Civil Rights Acts.[xviii] Enforcement of these civil rights codes would provide safe access to goods and services, and thereby keep them free of harassment and discrimination. Since streets and parks were the locations of 31 percent of hate incidents, we proposed targeted public education campaigns and signage on transit routes, streets, and parks.[xix] Recognizing that calls to changes in behavior are more effective than general awareness of an issue, we suggested signage reminding people to treat others with respect and to intervene in situations of harassment.

Following that meeting with the Governor’s Office, SAH has met regularly with the California DFEH to host public education webinars and to explore pursuing mediation of Asian American cases through its complaint procedures.[xx] We continue to investigate how we might use California as a model for other states in extending public accommodations and working with state agencies to curb anti-Asian harassment at businesses.

Conclusion

Through SAH’s data collection, research analysis, and policy advocacy, we learned about public policy by actively engaging in its formulation itself. Despite having to review hundreds of harrowing and even traumatizing accounts of anti-Asian hate, we have been heartened by the overall community’s resistance against racism. Elderly Asians and Asians with limited English proficiency made the effort to file reports to SAH. Ninety youth across the nation quickly responded to the call to stop the violence against AAPIs, and spent their summer working to address the issue. AAPI celebrities like Bowen Yang, Helen Zia, Tzi Ma, xmxtoon, Maulik Pancholy, and Jeremy Lin have spoken out on the issue at SAH’s Youth Campaign meetings. Across generations, ethnicities, and professions, the AAPI community stood up.

Through hands-on learning, we gained key lessons on the public policy process. In order to put anti-Asian hate on the agenda of policy makers, we needed to document major trends of racism impacting our communities. We had to frame the narrative about COVID-19 discrimination as rooted in systemic racism, so that the government would respond appropriately. In developing policies, we found that identifying solutions with a bottom-up approach was critical: impacted communities need to have a voice in addressing their own concerns. For example, our high school interns took the time to listen to their peers and consider their own experiences before creating their policy platform. And to advocate strategically, we had to understand the structure of government and existing policies so that we could promote our own priorities well. Identifying the appropriate authorities, their powers, and their own political agendas—whether they were the California Superintendent of Schools or the director of the Department of Fair Employment and Housing—helped us collaborate strategically to stop the bullying of AAPI youth in schools and the harassment of AAPI customers in stores.

SAH is now pivoting towards the next stage of the public policy process, that of policy implementation. Beyond retracting many of the anti-immigrant policies of the Trump administration, we look forward to expanding Ethnic Studies, extending civil rights protections, and promoting restorative justice models for community transformation. These policy approaches are promising practices as we seek to build a larger AAPI movement of justice and solidarity.

References

[i] Newsroom, “Pelosi Floor Speech in Support of House Resolution Condemning All Anti-Asian Sentiment Since the Outbreak of COVID-19,” 17 September 2000, https://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/91720

[ii] Stop AAPI Hate is a project of Chinese for Affirmative Action, the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, and SF State University Asian American Studies.

[iii] Russell Jeung, Manjusha Kulkarni, Cynthia Choi, “Trump’s racist comments are fueling hate crimes against Asian Americans. Time for state leaders to step in,” Los Angeles Times, 1 April 2020. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-04-01/coronavirus-anti-asian-discrimination-threats

[iv] Sabrina Tavernise and Richard A. Oppel Jr., “Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety,” New York Times, 2 June 2020.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/chinese-coronavirus-racist-attacks.html; Craig Timberg and Allyson Chiu, “As the Coronavirus Spreads, so Does Online Racism Targeting Asians, New Research Shows,” The Washington Post, 8 April 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/04/08/coronavirus-spreads-so-does-online-racism-targeting-asians-new-research-shows/; Anh Do, “’You Started the Corona!’ Anti-Asian Incidents Rise; As Hate Episodes Exceed 800, Activists Push Newsom for Help,” The Los Angeles Times, 5 July 2020, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-07-05/anti-asian-hate-newsom-help; Steve Mullis and Heidi Glenn, “New Site Collects Reports Of Racism Against Asian Americans Amid Coronavirus Pandemic,” NPR, 27 March 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/03/27/822187627/new-site-collects-reports-of-anti-asian-american-sentiment-amid-coronavirus-pand; Anna Purna Kambhampaty, “’I Will Not Stand Silent.’ 10 Asian Americans Reflect on Racism During the Pandemic and the Need for Equality,” TIME, 25 June 2020. https://time.com/5858649/racism-coronavirus/

[v] “They Blamed Me Because I am Asian” and other Stop AAPI Hate reports can be downloaded at https://stopaapihate.org/reportsreleases/.

[vi] Michael Howlett, Michael Ramesh, and Anthony Perl, Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[vii] Meera Viswanathan et al., “Community‐Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence: Summary,” Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, no. 18 (2004): 1-8. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8254093_Community-Based_Participatory_Research_Assessing_the_Evidence_Summary; Andrew J. Jolivette, ed., Research Justice: Methodologies for Social Change (Bristol, UK: Policy Press, 2015).

[viii] “About,” Stop AAPI Hate, accessed 11 February 2020, https://stopaapihate.org/about/.

[ix] Li Zhou, “How the Coronavirus is Surfacing America’s Deep-Seated Anti-Asian Biases,” Vox, 21 April 2020. https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/4/21/21221007/anti-asian-racism-coronavirus; Ali Rogan and Amma Nawaz, “We have been through this before: Why anti-Asian hate crimes are rising amid coronavirus,” PBS Newshour, 25 June 2020. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/we-have-been-through-this-before-why-anti-asian-hate-crimes-are-rising-amid-coronavirus.

[x] Marina Fang, “Trump Is The Biggest ‘Superspreader’ Of Anti-Asian Racism, Activists and Scholars Warn,” The Huffington Post, 21 October 2020. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-anti-asian-racism-covid-19_n_5f905c0fc5b62333b24133f5?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAANUw6GACBet0pDYSBAhzVDEZl0DK3udybbnTd6NQW7S5yJt6ii7LdxQOFdZbAg90cmRYwyWic8YjyenvxNJh1S6cUIgDa6vtdNYfSxk2vYT_ffLWeot-Y9P_SQ5VEJzZlIObTZc1W5xr4MBcIlMKGKGfamnHMFba00oX6WDyNH0z

[xi] Alexia Fernández Campbell and Alex Ellerbeck, “Federal Agencies are Doing Little About the Rise in Anti-Asian Hate,” NBC News, 16 April 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/federal-agencies-are-doing-little-about-rise-anti-asian-hate-n1184766

[xii] Kimmy Yam, “House passes resolution to denounce Covid-19 racism toward Asian Americans,” NBC News, 17 September 2020.https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/house-passes-resolution-denounce-covid-19-racism-toward-asian-americans-n1240385

[xiii] Claire Wang, “’Ching chong! You have Chinese virus!’: 1 in 4 Asian American youths experience racist bullying, report says,” NBC Asian America, 17 September 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/25-percent-asian-american-youths-racist-bullying-n1240380

[xiv] Randall Yip, “California Governor Ends His Presser by Calling out Racism, Brings up The Chinese Exclusion Act,” AsAmNews, 21 March 2020. https://asamnews.com/2020/03/21/california-governor-gavin-newsom-condemns-coronavirus-racism-and-xenophobia/.

[xv] Christine E. Sleeter, “The academic and social value of ethnic studies,” Education Resources Information Center, 2011. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED521869; Brooke Donald, “Stanford Study Suggests Academic Benefits from Ethnic Studies Courses,” Stanford News, 12 January 2016. https://news.stanford.edu/2016/01/12/ethnic-studies-benefits-011216/

[xvi] Jeff Wagenheim, “There’s Nothing Soft About These Skills,” Harvard Ed. Magazine, 2016. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/ed/16/01/theres-nothing-soft-about-these-skills; Astrid Mona O’Moore and Stephen James Minton, “Evaluation of the effectiveness of an anti‐bullying programme in primary schools,” Aggressive Behavior, vol. 31 (2005): 609-622. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ab.20098

[xvii] John Kidd and Rita Alfred, Restorative Justice: A Working Guide for Our Schools, ed. JoAnn Ugolini (Alameda County Health Services Agency, 2011) [PDF file]. https://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/D2_Restorative-Justice-Paper_Alfred.pdf

[xviii] “CACI No. 3060. Unruh Civil Rights Act – Essential Factual Elements (Civ. Code, §§ 51, 52),” Judicial Council of California Civil Jury Instructions (2020 edition). https://www.justia.com/trials-litigation/docs/caci/3000/3060/; “CACI No. 3063. Acts of Violence – Ralph Act – Essential Factual Elements (Civ. Code, § 51.7),” Judicial Council of California Civil Jury Instructions (2020 edition). https://www.justia.com/trials-litigation/docs/caci/3000/3063/

[xix] Lacey Meyer, “Are Public Awareness Campaigns Effective,” CURE, 15 March 2008. https://www.curetoday.com/publications/cure/2008/spring2008/are-public-awareness-campaigns-effective; Anne Pederson, Iain Walker, and Mike Wise, “‘Talk does not cook rice’: Beyond anti-racism rhetoric to strategies for social action,” Australian Psychologist, no. 40 (2005): 20-30. https://www.academia.edu/7177159/Talk_does_not_cook_rice_Beyond_anti_racism_rhetoric_to_strategies_for_social_action

[xx] Susan Jeghelian, Madhawa Palihapitiya, and Kaila Eisenkraft, “Legislative Study: A Framework to Strengthen Massachusetts Community Mediation as a Cost-Effective Public Service,” Massachusetts Office of Public Collaboration Publications, 2011. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/mopc_pubs/1