Throughout this spring of 2023, the world is witnessing a global surge in COVID cases, driven by variants of the virus such as the XBB.1.16 strain in India and the XBB.1.15 in the United States.1 The COVID crisis has glaringly underscored the need for nation states to prepare for the advent of global pandemics. Lockdowns are a crucial component of the response arsenal that states have when dealing with pandemics for which vaccines are yet to be invented. The lessons from India’s experience of executing one of the world’s largest lockdowns during the first wave of COVID in early 2020 can help prepare the world for the next pandemic, or even the next wave of the same disease. Particularly, India’s experience can elucidate best practices in pandemic law enforcement that can serve as a template for future international crises drawn from the world’s largest democracy.

On March 24, 2020, India had approximately 500 active, identified cases of COVID-19.2 As a precautionary measure to quell the steady rise of cases, the central government announced what would become the most stringent lockdown in the world.3 The government lockdown officially ended on May 31, 2020 and six phases of re-opening were administered through November 2020. It is estimated that the timely imposition of phased lockdowns in the first wave of transmission averted 1.5 to 3 million cases, thereby saving 37,000-78,000 lives.4 Daily reported cases dropped to an all-time low of 9,000 by February 2021.5

The second wave, however, ballooned the daily number of reported cases and deaths, to 400,000 and 3,500, respectively (as of April 30, 2021).6 In response to the staggering health crisis, as states announce new lockdowns to contain the pandemic, public health officials should heed lessons learned from the micro-level implementation of the lockdown in the first wave of transmission that can be replicated in this ongoing second wave.

The pandemic’s impact on cities and urban areas has dominated the narrative—with a focus on the service sector, the industrial labor crisis, social distancing, and the normalization of “work from home” policies. However, in the Indian context, it is also worth highlighting the pandemic’s impact on the vast rural hinterland, and accordingly the mobilization of local law enforcement agencies in these regions.

In the state of Maharashtra, the Beed district police served a crucial role in the community despite rural-specific challenges. Beed is located in the heart of the state and spans an area of nearly four-thousand square miles. Three million people live within its borders and constitute a primarily agrarian society. The district is closely linked economically and socially with the cities of Pune and Aurangabad (both of which have emerged as major COVID-19 hotspots in the preceding months), with constant population movement between each of these cities and Beed.

In April and May of 2020, seventy thousand sugarcane laborers returned home to Beed from the afflicted districts of western Maharashtra. Unlike cities, homesteads in rural areas are not self-contained spaces in which families can isolate themselves for extended periods. It is tremendously difficult to persuade the population to indefinitely quarantine in these spaces. In rural areas with limited digital literacy, disinformation on the internet and social media continues to prevent the dissemination of accurate information.

Despite these aggravating factors, Beed remained reported nil infections since the advent of the pandemic, until relaxations to the lockdown were announced. The overarching principles that have informed the police’s strategy are empathy, awareness, and firmness.

Empathy: Supporting Communities in Coming to Terms with the Crisis

- A comprehensive and responsive pass system – The key limitations imposed by consecutive lockdowns were restrictions on movement and the consequent disruption to emergency services. The state swiftly adopted a system of quick response coded passes, with police teams working nonstop to approve 70,000 emergency service providers within twenty-four hours of application. This system sanctioned passes for citizens with personal emergencies who needed to access advanced medical facilities in major cities. The unit ensured these passes were verified and sanctioned within half an hour of application due to their time-sensitive nature. These police teams enabled more than 3,000 citizens to access medical facilities across the state despite the rigor of the lockdown.

- Coordination of returning labor – Beed is a source of agricultural migrant labor for the sugar industries of western Maharashtra and northern Karnataka. The lockdown created a crisis where thousands of families who migrated to these regions for sugarcane fieldwork were stranded for months in sugar factories, unable to return home. Unchecked and uncoordinated movement of these families could result in the spread of the virus and also create a law enforcement crisis at district borders.

A control room at police headquarters coordinated the staggered movement of laborers through nineteen designated border entry points. This ensured inward routes were not overwhelmed by any bottlenecks. At entry points, every returning laborer was screened for symptoms to halt the spread of disease. Over 160,000 laborers crossed the borders of Beed and were reunited with their families without any resulting deaths.

- Distribution of food grains and groceries – Beed is a drought-stricken district where water shortages have limited agriculture. Hundreds of villagers across the district generously contributed grains and vegetables to the police, who distributed them to those most in need. Almost overnight, police stations transformed into granaries, supplying food to families economically crippled by the lockdown. Police officers were delivering these life-saving rations.

- Domestic violence helplines – The Indian mainstream discourses on the pandemic have often omitted mental health information and effects. This severely affected families, where women, children, and senior citizens bear the brunt of physical and mental aggression by male heads of household. In a rural setting, the usual port of call for such survivors is the nearest police station. However, women rarely have access to independent transportation and cannot reach the police station in the absence of public transportation. To remedy this, helplines were created for domestic abuse survivors to seek immediate police intervention. During the lockdown period, police teams in Beed resolved 132 cases of domestic violence through mediation, legal action, and educational home visits where police acquainted perpetrators of legal consequences if violence or ill-treatment continued.

Awareness: Leveraging Knowledge, Our Best Weapon Against the Virus

Given the prevalence of data services in rural areas, the internet remains the predominant source of information for village communities. It is vital for law enforcement agencies to intervene in the information dissemination process to counter fake news and provide facts with credibility and authority. In Beed, the police used a wide range of methods to achieve this:

- Coordination with religious leaders–Religious leaders in nearly all communities enjoy a level of influence unrivaled by any other organization. Police officials recruited religious leaders such as pandits, maulanas, and monks to convey the lockdown protocols in short videos.

The real impact of this initiative was felt during festivals and spiritual celebrations. The lockdown period coincided with some of the biggest festivals of the calendar: Ram Navami, Hanuman Jayanti, Shab-e-Baraat, Ambedkar Jayanti, Ramzaan, and Eid. While these festivals typically garner crowds in the hundreds of thousands, not a single congregation was seen during lockdown, in part due to the efficacy of the awareness campaign.

- Awareness videos by senior police officers – Faced by constantly changing regulations, it is essential to communicate the rules and their rationale to the public in simple terms. In Beed, senior police officers delivered authorized, up-to-date information in regularly posted videos. These videos covered topics such as the latest policy changes, the process of pass disbursal, and how to use a pulse oximeter. These videos served as an authoritative source of genuine information, cutting through the specter of fake news.

Social media monitoring cell – While awareness is the main focus in internet safety discussions, it must be accompanied by consequences for those who disingenuously operate in cyberspace. The social media unit of the district police monitors hashtag and keyword searches on social media platforms for fake news, rumors, and hate speech. They also monitored content in active WhatsApp groups. Beed had the highest number of actions taken against fake news and hate speech during the pandemic.

Firmness: The Role of Enforcement in Containing the Contagion

- Border sealing – Sealing the district borders and maintaining strict control on migration was the first and most significant measure taken in Beed. In rural Indian districts, it is not sufficient to impose checkpoints at each of the border entry points. Beed is a landlocked district and shares contiguous borders with six other districts, which people can travel between on several internal village routes. The police identified and excavated more than three hundred such routes in order to prohibit the movement of unscreened people from infected regions of the state.

- Gram Suraksha Dals – Despite endeavors to seal the district borders, it is impossible to entirely prevent people from reaching villages within the district. A village level intelligence mechanism was formed consisting of the Sarpanch, the Police Patil, and the Tantamukta Adhyaksh (elected village officials). This committee informed the police each time an unscreened person returned to a village. These people were then tested for symptoms and placed under quarantine.

- Contact Tracing Cell – It is crucial to identify people who were in contact with an infected person. This requires organizational coordination for interviewing, surveillance, and detection. The Contact Tracing Cell unit traces the previous contact history of infected individuals through personal and technical intelligence. As a result of this unit, over 350 individuals were successfully taken into medical custody for institutional quarantine.

- Geo-fencing of home-quarantined individuals – Home quarantine enforcement posed a unique challenge to police in rural areas. Houses are typically disparate and often located at great distances from the nearest police station, which limits surveillance. A village house is typically used only for sleeping, and it lacks the entertainment facilities that can enable people to stay indoors for extended periods. In order to achieve effective home quarantine, three forms of surveillance were leveraged in Beed:

- A GPS-based app called Life 360 permitted a closed user group to track all the members of the group.

- The houses of people who are placed under home quarantine are geo-fenced so that any movement outward or inward can be traced.

- A beat constable, police patil,7 and a village employment officer checked physically on households.

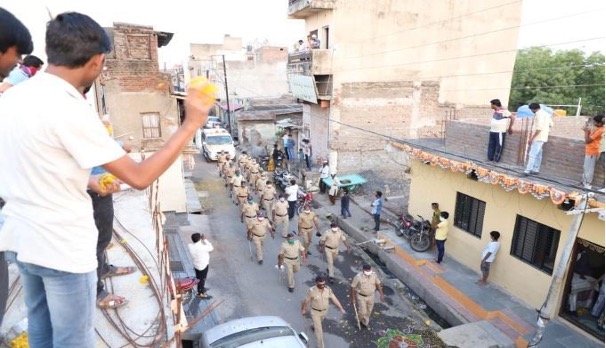

- Area Domination – In addition to border management, it was important to place restrictions on the interactions between the three million people within Beed. To enforce the lockdown for over two months, police mapped places of regular public congregation and controlled fixed points and regular route marches. The police patrolled the internal roads of each city with drones. In a vast district, aerial surveillance and mapping enabled coordinated patrols in zones where lockdown enforcement was most necessary.

Since all Beed residents were not subject to the same lockdown guidelines, mobility restrictions were implemented with discretion. Social distancing protocols were generally aligned with the nature of agricultural work. Given that field laborers do not crowd each other, farmers were completely exempted from the lockdown regulations, to prevent a future food crisis.

This pandemic added a new chapter to the history of the Maharashtra Police, one which has forged a new relationship between the police and citizens– with empathy, trust, and commitment. Beed’s example teaches us it is crucial that governments see lockdowns through the prism of facilitation rather than enforcement alone. Realistic predictions of socio-economic dynamics during the period of the lockdown go a long way in achieving this goal. Most importantly, rural communities need to play to their strengths in handling the contagion rather than emulating urban methods. Relative availability of space, self-reliant consumption patterns, close knit communities—aspects that define rural societies—can become some of the most impactful weapons in this battle.

[1] https://time.com/6268467/omicron-subvariant-xbb116-covid-19/

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/world/asia/india-coronavirus-lockdown.html

[3] https://www.cnbctv18.com/healthcare/study-reveals-indias-response-to-coronavirus-most-stringent-5666531.htm

[4] https://www.businessinsider.in/india/news/no-of-covid-19-cases-averted-due-to-lockdown-is-in-14-29-lakh-range-37000-78000-lives-saved-govt/articleshow/75894356.cms

[5] https://edition.cnn.com/2021/04/05/india/india-second-wave-covid-intl-hnk/index.html

[6] https://edition.cnn.com/world/live-news/coronavirus-pandemic-vaccine-updates-05-01-21/h_cdd6ab036620523ad156b8347c47448f

[7] A designated resident of the village employed to liaise with the police administration on law and order and crime issues pertaining to the village.