“I do not conceive how someone who loves nothing can be happy.”

—Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, Book IV

“Tonight we are just going to have a lesbian night in.”

“What makes it a lesbian night in?”

“Oh, the fact that it is a night in.”

—A.A, personal communication

(emphasis added)

“Don’t let them in

I am too tired

To hold myself carefully

And wink when they circle

The fact that I’m trapped

In this body”

—Perfume Genius, Don’t Let Them In

Aims and Summary

Part of the human experience is showing affection to those whom one loves or cares about. These displays of affection, termed intimacy in this piece, are also restricted and regulated by social processes and policies differentially for different groups of people.[i] This piece sets out to examine how intimacy for one group of people—queer people—is restricted and regulated in the United States by one prevalent and pervasive social process—stigma—and what can be done to ensure this population has equal opportunity to express intimacy and thus achieve full personhood.[ii]

To achieve this, this piece: i) briefly introduces the reader to the stigma concept, its impact on queer people, and how little is known about how stigma relates to queer intimacy; ii) uses qualitative methods to explore the mechanisms by which stigma regulates queer intimacy; and iii) discusses the potential ways a human rights approach may assist efforts to combat this inequity.

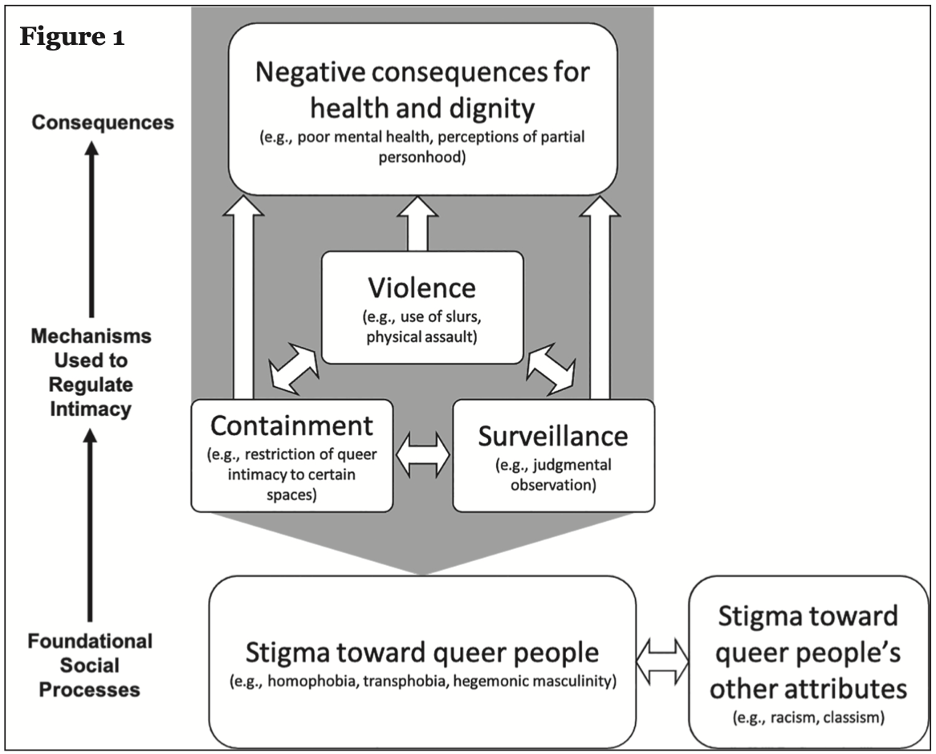

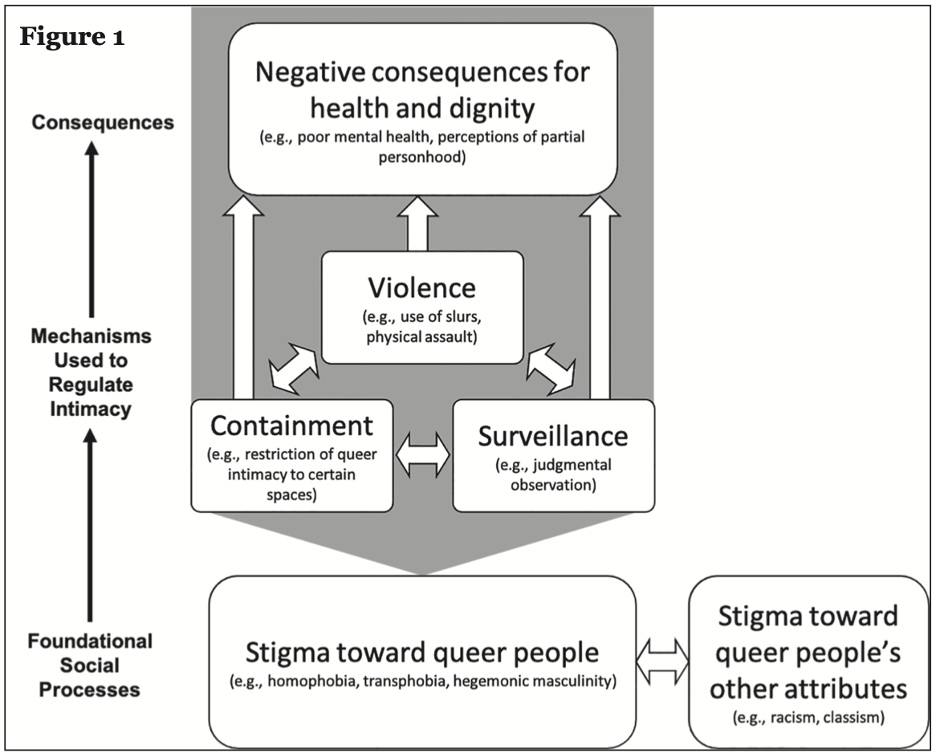

Briefly, three mechanisms through which stigma regulates queer intimacy emerge from the qualitative data: surveillance (e.g., judgmental observation), containment (e.g., restricting queer intimacy to certain spaces), and violence (e.g., use of slurs, physical assault). Together, these mechanisms negatively impact queer people’s health and prevent a full realization of their dignity; separately, they offer three points at which policies can be designed to target, work against, and prevent stigma against queer intimacy. Some existing policies can be seen as combatting these mechanisms, but still more are needed to help ensure queer people have equitable access to this core facet of human experience.

Stigma, Queerness, and Intimacy

Erving Goffman’s landmark work Stigma was published in 1963, and the proliferation of related research in the decades since has revealed stigma’s pervasive and pernicious role in society.[iii] The definition of stigma has considerable variability in the social science literature, but most scholars agree that it somehow pertains to its original Greek meaning of a “discrediting mark”—that, in some way, stigma is a means of marginalization and othering.

Additionally, although stigma’s primary use long ago was for undesirable physical traits, this has shifted and broadened. These days, following Erving Goffman’s expansion of stigmatization to the bases of identity and behavior, social psychology’s delineation of ways stigma negatively impacts individuals’ health and well-being, and Jo Phelan and Bruce Link’s sociological conceptualization of stigma being anything that society uses to restrict an individual into a perceived-inferior social position, almost any trait could be a basis for stigmatization so long as there is a power differential between the stigmatizer and the stigmatized.[iv], [v], [vi], [vii], [viii] Along with working toward increasing clarity of what and who can be a target of stigma, scholars have also been mapping the ways stigma operates on different levels. Stigma has been documented to operate on macro, meso, and micro levels—ranging from the structural (e.g., laws and policies) to the interpersonal (e.g., enacted stigma, or discrimination) to the internalized (e.g., felt stigma, internalized stigma, self-stigma).[ix], [x]

Like all other stigmas, stigma on the basis of sexuality and gender identity has long been shown to be highly prevalent and damaging and exists at all levels. At the structural level, queer people have been subject to various laws and policies that seek to regulate their ability to marry; their access to health care, housing, and employment; and their achievement of a variety of other core human capabilities and needs.[xi], [xii], [xiii] Public attitudes, too, are still far from completely accepting and affirming queer people.[xiv] This hostile policy environment combined with stigmatizing public attitudes can manifest in harmful interpersonal interactions (e.g., bullying, heinously high rates of anti-trans violence and homicide) that further produce and reproduce stigma toward queer people.[xv],[xvi]

Stigma across all of these levels has been shown to be internalized by queer people, leading to worse health and well-being despite positive trends in public attitudes toward queer people.[xvii], [xviii] It is important to note, though it is not the focus of this paper, that stigma toward HIV/AIDS and stigma toward sexual and gender minorities are and have been inextricably linked in complex, lasting ways.[xix] Although how stigma negatively impacts queer people’s health and well-being is increasingly well documented, its impacts on specific behaviors are largely neglected.

One behavior that is experienced differently between queer and non-queer individuals is the public expression of intimacy.[xx] There are ways in which non-queer people can and do express intimacy with people of the same gender, but these sorts of intimacy are regulated by other specific, culture-specific sets of social rules and rituals.[xxi]Queer people, however, exist and perform these behaviors in such a way that is not within these set social rules around gender and sexuality.[xxii] In other words, because public expression of queer intimacy between queer people is a display of queerness—a way of being that is often socially deemed deviant or discrediting—and not within what is deemed to be socially acceptable, the public expression of queer intimacy between queer people can put queer people at high risk for experiencing stigma.[xxiii]

Even though it may seem obvious that expressing intimacy can elicit stigmatization, how exactly this occurs and how it is felt and experienced by queer individuals is not well known. Many stigma researchers will acknowledge that stigma is a “black box,” and its exact mechanisms can vary and elude understanding. In an attempt to shed light on this one small part of stigma’s various processes, queer individuals’ experiences with stigma—particularly when expressing intimacy—is further explored in the following qualitative data analysis.

Characterizing Stigma’s Regulation of Queer Intimacy through Qualitative Methods

To begin to explore and characterize the potential mechanisms through which stigma regulates queer intimacy, this section draws on qualitative data from six semi-structured interviews with queer-identifying individuals and an ethnography of a New York Public Library-sponsored event in April 2019 entitled “Intergenerational Queer Friendship: A Community Conversation.” Data collection, management, and analysis details are described in Appendix I. Limitations to this methodology are discussed in Appendix II.

Three salient mechanisms by which stigma regulates the expression of queer intimacy emerged from a thematic analysis of the data. Two mechanisms—surveillance and containment—were made explicitly clear as ways that participants saw stigma operating on and around them. The third mechanism—violence—is well represented in the literature and emerged infrequently in the data, but it was not explicitly labeled by participants as a stigma mechanism. These three mechanisms operated independently and interactionally to generate feelings of being watched, perceptions and experiences of being relegated to specific spaces, and fear of encountering violence—all of which together served to restrict and regulate participants’ expression of intimacy. A schematic of these mechanisms is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic of Stigma’s Regulation of Queer Intimacy

Mechanism One: Surveillance

A concern mentioned by all queer individuals interviewed was surveillance.[xxiv] Participants reported distress about being specifically watched (i.e., surveilled) not only when existing generally but especially when with a partner. While going about their day-to-day alone or with other queer individuals, participants reported concern about being labeled as queer and subordinated through surveillance, about being “watched for being different.” One participant directly attributed this feeling of being othered as tied to people’s gaze:

That’s why I generally dress in more muted colors. I don’t like to draw people’s attention to me, and . . . for two men to hold hands walking down the street—[in many places] that will draw a lot of attention [. . .]. [People would] be like, “Oh! What are they doing?”

Not only were these participants anxious about being watched, they changed their behaviors accordingly. They reported avoiding going outside in the daytime so they are not as visible or wearing muted colors to avoid attention—or, as one participant put it, “I make sure that I appear normal, to sort of be [. . .] an anomaly is one thing I don’t like.”

Sometimes queer people’s concerns around surveillance are compounded by non-queer-specific fears of surveillance related to being seen as a vulnerable member of any number of stigmatized populations. One older adult at the community event who identifies as a “butch lesbian” described how—in her youth—she began altering her gender presentation by binding both as a way appear more “masculine” to the public when with a female-presenting partner to more freely express intimacy (i.e., so that they would appear as a heterosexual couple) and as a way to resist experiencing female-targeted assault while experiencing homelessness as a teenager in the West Village neighborhood of New York City.[xxv] Moreover, surveillance can be a concern throughout one’s life. This same participant has continued to bind to this day and explicitly attributed that behavior more to an ongoing concern of being seen as queer rather than her own desire around her own gender presentation:

Whether I was with [a partner] or not, I bind. This is what I do, this is how I’ve looked forever, and [even though I bind] I’m still always feeling watched for being different, always looking over my shoulders.

The hesitancy to express queer intimacy—which may be a rare occurrence—seems to be situated in a larger overarching concern of surveillance of daily existence. Queer people are already concerned about public perception due to a history of discrimination, violence, and harassment queer people have endured, and participants articulated how doing something that would make their queerness more obvious (i.e., expressing queer intimacy) seems to only elevate the chance that their identity would be perceived by stigmatizers and thus raise the possibility of negative subsequent consequences (e.g., containment, violence—below).

Mechanism Two: Containment

The second of the two mechanisms that emerged from the qualitative data is containment.[xxvi] All six interviewees suggested that there are indeed places and spaces where they are perfectly comfortable with expressing queer intimacy or their queer identities more generally—largely ones that have been made by or for queer people. Participants explained how these spaces in which queer intimacy is comfortably expressed exist in direct contrast to public spaces, where the ability to freely express queer intimacy may be uncertain because of default expectations of cisheteronormativity and associated stigmas. This paper names this phenomenon of queer intimacy being permitted to freely occur only in specific places as containment.

The most frequently mentioned of these places where queer intimacy is contained are gay clubs or bars. One participant described the expression of intimacy being so much of a non-concern in gay clubs that he finds himself being intimate with other queer individuals without necessarily intending to be:

If you go to a club, you’re gonna dance [. . .]. They’re always very crowded so you’re going to be—depending on the type of club—always touching other people, and it is for sure intimate sometimes and it for sure feels good.

Participants described little to no hesitation in expressing queer intimacy in queer nightlife, and this seems to be attributed to the characteristics of the clubs or bars themselves, including the lack of daylight and space and the presence of loud music and inhibition-reducing substances.[xxvii] Another participant further described what may drive the expression of intimacy in a gay club and make it different than public space:

[A person in a club would] probably be more encouraged by alcohol and tight spaces and loud music and . . . the night [laughs]. I’d say those things combined make a gay club a place where a lot of intimacy happens—in the open.

But specifically queer spaces are not the only places that queer intimacy can occur freely, and other places are sought out. As one participant noted:

I grew up in small town in Ohio, and I knew all the [people who were queer] and we didn’t have a space to feel ourselves except in each other’s homes. So people’s houses—that’s where we’d go and sometimes cuddle, not even if we are dating, just so we can have some physical touch.

Here, in a sentiment echoed by other participants who had spent time in places where queer-designated spaces were not available, (re)claimed queer-friendly private spaces seem to offer a place to gather for queer individuals in which they can “feel [like] themselves” and express platonic or non-platonic intimacy. Notably absent from these places is the concern of surveillance; gay clubs and bars and people’s homes (and certain parks and cities such as San Francisco mentioned in other interviews) all lack the heteronormative gaze. Being in a contained place where you are not surveilled seems to allow queer intimacy to be freely expressed by those who want to express it.[xxviii]

Mechanism Three: Violence

An additional mechanism much more represented in the literature than in the qualitative data is violence. It is necessary to include a discussion of the violence—both verbal and physical—that is often directed at the queer community; the previously discussed mechanisms of surveillance and containment may make the stigmatization of queer individuals seem unduly passive. In fact, there are concerns of experiencing violence underlying both of the other mechanisms; if one is seen expressing queer intimacy by the wrong person or in the wrong place, they are at high risk of violence.[xxix] This risk of violence is not only incurred when expressing queer intimacy with a partner, but also for otherwise “doing gender” or sexuality in a way that is seen as incorrect.[xxx]

The concerns about violent confrontation were largely absent from the qualitative data—save for one mention about being scared about being “beat up” for being visibly queer during the community conversation, which was met with many assenting nods. This omission could be due to a changing focus of queer resistance (i.e., a shift from anti-establishment to assimilationist), the age of the interviewed participants (the one mention was from a person who appeared to be in their mid- to late-sixties, who may have experienced more violence in past decades), and/or an unwillingness to disclose fears and experiences of violence during an interview.[xxxi]

Positioning Stigma’s Regulation of Queer Intimacy as a Human Rights Issue

As seen in the current literature and the qualitative data collected here, there is indeed a disparity in the ability to express public intimacy between queer and non-queer individuals. These data have revealed how stigma, in large part due to surveillance and concerns about violence, contains queer intimacy to certain places and limits its expression. This is an affront on queer individuals’ rights. This restriction on the expression of intimacy exacerbates already-existing disparities between queer and non-queer populations’ ability to maintain health and infringes on queer people’s dignity—two concepts defended by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Article 25 of the UDHR defends the right to health broadly, stating that “[e]veryone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself (sic) and of his (sic) family.”[xxxii] Furthermore, the document in its entirety rests on the assumption of an “inherent dignity” that is and should be “equal” that exists for all people.[xxxiii]

Maintenance of Health

The stigmatization of queer populations and its restriction of the expression of queer intimacy prohibits the full realization of the right to health. Public health and social science research has drawn associations between stigmatization and lowered health indicators across dozens of conditions, leading stigma to have been proclaimed a fundamental cause of health inequities in the American Journal of Public Health.[xxxiv] Narrowing in on stigma’s effects on queer individuals, studies have shown that there is stigmatization of queer individuals on multiple levels, largely in the interpersonal (relevant to the surveillance and violence mechanisms) and structural (relevant to the containment mechanism) domains that all lead to poorer health.[xxxv]

Operating on the interpersonal level, surveillance keeps queer individuals from expressing intimacy in sight of others that may hold stigmatizing views in the same places where non-queer individuals would be able to express intimacy. The sorts of behavioral regulation reported by the participants may begin early in life and may go further than just dressing or doing things differently. A 2008 study found that young queer individuals (aged 16–25 years) in the northwest of England and South Wales not only took steps to appear less visibly queer but also often engaged in self-harming or suicidal behavior as a means to cope with minority stress.[xxxvi] This example makes it clear that not having full freedom of expression—including expression that might label someone as queer, such as expressing queer intimacy—can affect queer individuals throughout their lives and have serious and sometimes fatal health consequences. Stigma and the surveillance it employs generate and exacerbate health disparities for queer people.

Operating on the structural level, containment has also been shown to have its own negative impact on queer individuals’ health. At the political-geographic scale, states with less LGBTQ-favorable policies have queer populations with worse health indicators than states with more LGBTQ-favorable policies. [xxxvii] This constrains queer people from having the full ability to achieve health unless they are in certain places. More granularly, on the hyper-local level, as suggested by the qualitative data, queer intimacy is confined to queer or queer-friendly spaces such as queer clubs, bars, or private residences. Clubs and bars could also facilitate substance use (e.g., drinking alcohol, the use of illicit substances) that in turn raises the risk of unwanted sexual activity. This adds a sexual health concern to the mental health one; stigma may relegate queer intimacy to spaces that diminish queer people’s capacity for maintaining sexual health. Through the mechanism of containment, too, the realization of the right to health is limited by the stigmatization of queer intimacy.

Maintenance of Dignity

These health indicators are relatively easy to measure, but health is not the only rights-based concept that stigma’s regulation of queer intimacy negatively affects. Although perhaps more abstract than quantifiable health indicators, stigma’s regulation of queer intimacy also damages queer individuals’ dignity. Martha Nussbaum gives perhaps the most impassioned argument of how any type of shame, including stigmatization as arguably one type of shame, is a direct affront on human dignity.

In her book Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law, Nussbaum expands on Julia Annas’s conceptualization of shame that targets the whole person, stating that shame is especially likely to result in or from “a broken spirit.”[xxxviii] The shamed, a category that includes the stigmatized (e.g., queer populations), end up having a persistent inability to form or recover a sense of wholeness—of dignity—as a result of society’s stigmatization of them.[xxxix] When queer people are unable to be their full selves and achieve the full range of human capabilities—including intimacy—in the same un-surveilled, uncontained way without fear of violence as their non-queer peers, their dignity suffers.

But queer people are not the only population that should be concerned about this affront on dignity; Nussbaum also gestures toward the way stigmatization does not solely infringe on the rights of the stigmatized alone. Nussbaum and Goffman both posit a sort of feedback loop between denormalization and normalization—that the stigmatization of groups labeled as deviant enables a relative normalcy or non-deviance. In Stigma, “stigmatized individual” and “the person [the normal person] is normal against” are used interchangeably, equated.[xl]

Gender theorist Raewyn Connell explains stigma’s feedback loop, at least in the sphere of gender, as a mechanism by which the hegemonic maintains its domination—the normal is, in fact, toxic.[xli] Stigmatization of queer individuals and its regulation of the expression of queer intimacy, then, allows the normalization and persistence of an unhealthy hegemonic ideal of relationships that few—even non-queer people—can live up to and may therefore present a larger burden to society than what may be more immediately apparent. Stigmatization of queer individuals—including the restrictions it places on queer intimacy—is a human rights issue not restricted to queer populations, and it deserves swift and innovative policy action.

Policy Recommendations

First, ratification, endorsement, and promotion of human rights could in and of itself be considered anti-stigma work. Human rights as a framework can be viewed as overly reliant on platitudes and something that results in little tangible benefit beyond surface-level change—or worse, extends an exploitative, hegemonic, Western, neoliberal system of power.[xlii], [xliii] Any way you look at them, however, human rights and stigma are both largely invisible and operate in complex ways on all levels from the most abstract to the most personal.[xliv] Thus, the recognition of the inherent humanity of stigmatized people (e.g., queer people) and their right to dignity is maybe the closest thing to the opposite of stigma available.

This piece does not seek to make grand or intricate claims about how human rights and stigma are interrelated except to say that acknowledging the human rights and personhood of queer people certainly does not increase stigma toward queer people and in fact likely decreases it. In intangible ways, attempts to recognize queer people’s human rights (e.g., the Biden administration’s “Memorandum on Advancing the Human Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Persons Around the World”) almost surely lessen the power differential between queer and non-queer people on which stigma relies, thus decreasing stigma by making it more difficult to carry out.[xlv] To think about possibly more tangible ways that stigma’s negative impacts on queer intimacy, queer people, and society can be mitigated, this piece’s three mechanisms via which stigma regulates queer intimacy offer at least three points that rights-focused policy can target.

Surveillance is likely the most difficult mechanism of the three to address. Implicit in being stigmatized is being seen to be different, so one way to counter judgmental observation of queer people and queer intimacy would be to increase the frequency and complexity of depictions of queer people and queer intimacy in various forms of imagery (e.g., media, advertisements). This is ongoing; for example, there is an increasing number of queer characters—who then also sometimes express queer intimacy—on television shows.[xlvi] These depictions are one small way to make the observation of queer people less judgmental and make surveillance a less harmful and effective mechanism. In addition to the interpersonal level, thinking about ways that policymakers and structures see queer people is essential in adjusting society’s surveillance. Ways that increase and normalize the ways systems see queer people—such as including more inclusive questions around sexual orientation and gender on the US Census and other governmental and institutional forms—are needed to ensure that queer people are also seen at this level. Importantly, current efforts to increase visibility of and normalize the existence of all queer people are not equal across queer subgroups (e.g., visibility of trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming people is lagging)—nor across race/ethnicity, ability, and many other axes of difference.[xlvii] These inequities must be recognized and corrected going forward to ensure that visibility is as effective as possible in reducing stigma toward all people.

Similar to surveillance, containment can be countered on both more interpersonal and more structural levels. Interpersonally, there are easy ways to signal that a place that may not be immediately assumed to be safe and inclusive of queer people and queer intimacy is, in fact, safe and inclusive. Rainbow “Safe Zone” stickers adorn many teachers’ offices, and Pride flags are in the doors of many businesses and even churches, establishing them as places that will be proactively inclusive of queer identity and expression.[xlviii] Even better for queer people and their ability to express intimacy than this “patchwork” approach to affirmation, however, are institutions and government making uniform, clear, unequivocal policies that queerness will not be a basis for exclusion.[xlix]

Returning to the idea of LGBTQ-favorable state policies, working to ensure that all states have LGBTQ-favorable policies would be one way to counter queerness limiting individuals’ health and dignity wherever they choose to live. Unfortunately, just having uniform inclusive policies and procedures is not enough to ensure they are uniformly enforced in all settings. First, places in the United States are sorted into public and private, and protections extended to queer people in public places may not extend to private ones. Second, even if queer intimacy is not contained to certain places, surveillance is now ever-present and constant, and judgmental observations may still push queer people out of spaces where they are officially included.[l] Acknowledging how these mechanisms interact also reveals how acting on one mechanism alone will be insufficient.

Approaches to countering violence would have to occur mostly on the structural level. First, at perhaps the most abstract level, leaders’ condemnation of violence against queer people (e.g., Obama’s condemnation of the Pulse nightclub shooting) is important in that it communicates on at least some high level that violence against queer people is not accepted.[li] Hate crime laws are another arena in which protections for queer people could be extended. Although the federal government includes sexual orientation and gender identity in their hate crime laws, only 23 states, two territories, and Washington, DC, explicitly enumerate both sexual orientation and gender identity in their hate crime laws. Eleven states have hate crime laws that enumerate only sexual orientation, and 13 states’ laws cover neither; three states and three territories have no hate crime laws, and one—Tennessee—interprets its hate crime laws to include sexual orientation and gender identity even though it is not explicitly included.[lii]

Efforts are underway, too, to repeal various laws and ordinances that are disproportionately used to arrest and detain trans people, especially Black trans people and those of color (e.g., the recently repealed “Walking While Trans Ban” in New York State).[liii] Attempts to end bullying of queer youth—which is both highly prevalent and highly damaging—such as establishing Gay-Straight Alliances and similar programs have been finding some successes in reducing reported experiences of bullying and increasing perceived social support.[liv], [lv] These are only a few examples of the many ways violence will need to be countered to reduce stigma. Violence can occur wherever queer people are surveilled and even where they are contained to exist out of sight (e.g., nightclubs). Knowing that the pervasiveness of violence serves to advance stigma toward queer people in so many ways and in so many spaces underscores the need for a litany of policy responses to reduce violence in all settings.

Conclusion

Stigma toward queer people is prevalent, pervasive, and extremely harmful, and it limits equal and free expression of intimacy—a core part of the human experience. Through a preliminary qualitative exploration, stigma was shown to regulate intimacy through the three highly interrelated mechanisms of surveillance, containment, and violence. Understanding these three mechanisms and their interrelations can inform policymakers’ decision making regarding how policies do or do not address these mechanisms, how they may or may not be effective at reducing stigma, and thus how they may or may not improve the health and well-being of queer people in this way.

Seeing that both stigma and human rights operate on similar macro levels, advancing human rights can also be a guiding approach for how to best counter stigma across all three mechanisms. Looking at these stigma mechanisms through a human rights lens prompts key strategies of affirming the human rights of queer people; increasing the visibility of queer people; working to ensure equal, consistent polices around queer inclusivity in and across all places; and working against violence against queer people on all of the many fronts it occurs. Finally, these strategies closely mirror what has been done and urged by queer activists for decades, and this analysis and framework is meant to bolster their long-standing work and hard-won gains from yet another angle.[lvi] Human rights-informed policymaking grounded in lived experiences and realities of stigma will help make it easier for queer people to lead the dignified, freely intimate lives they deserve.

Appendices and references attached.

Eschliman-u2013-Out-of-the-Closet-but-in-the-Shadows_FINAL