“I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories others have miswritten about me, about you.” — Gloria Anzaldúa

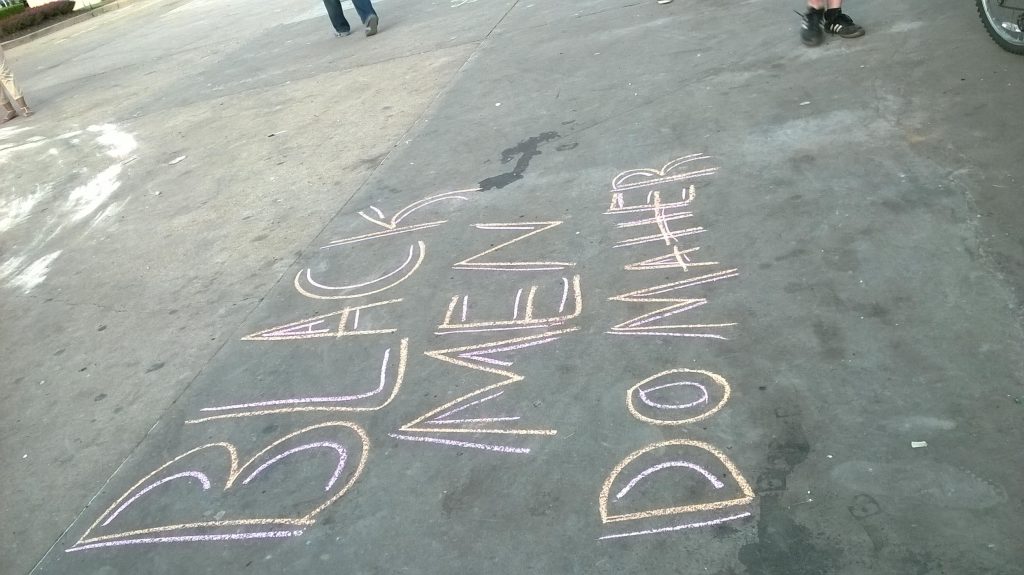

Photo by Mary Glen Fredrick 8/12/2014

Every time someone at school asks me about my city and its “chaos,” I ask them about their line of thinking: “What’s so chaotic about my city?” Most of them refer to the QuikTrip fire or the looting. I then reframe the conversation.

I explain that Ferguson became relevant and “chaotic” when Darren Wilson unconstitutionally killed Mike Brown, an unarmed teenager who was fleeing from him.

I then explain that when I was home, I felt like a crazy person. I felt like a crazy person because I was unable to reconcile the differences between what my eyes witnessed and what my television portrayed.

Each time I watched the news, the “coverage” was actually just a replay of looting and burning footage from the first eruption. The tear-gassing was not a result of civil unrest and violence “experienced” every night. Peaceful protestors were tear-gassed. Every night.

I felt like a crazy person because what I witnessed, what I experienced, wasn’t dictated on the news. What was the news talking about? Why were they lying?

Days before the news reported it, I stood in the street—facing tanks with headlights illuminating at maximum intensity. We couldn’t take pictures then because the lights were so bright. Officers stood facing us in tactile gear, military-grade weapons drawn. If we took a step within five yards of them, they would immediately raise their weapons—even with our hands above our hands.

Although the tear gas has since cleared, the peace surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement is becoming increasingly disturbed. But as we advocate, organize, and mobilize, we must also ensure the truthful telling of our stories—ensure that our accounts, our efforts, our momentum, and our progress is rightfully and validly portrayed.

There is much work to do.

“When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.” — Bayard Rustin

Michael Brown Jr. is the reason why my words are relevant. He is the reason why these photos are relevant.

I am from St. Louis. I was raised in the city, spent my summers in Ferguson, and lived half a mile away from where Michael Brown laid on the hot pavement for four hours. I went to college in Kansas City and was home visiting family just days before heading to law school. Michael was killed Saturday, August 9, 2014, and I was home by that following Monday. My husband Grandon, my mother-in-law, and I were watching the news when we saw images of police officers surrounding my old neighborhood. Ten minutes later, Grandon and I found a small back road into North County so we could head towards Ferguson. This road was blocked off by the police, as were the rest of the streets in about a six-mile radius. Despite this, the crowd continued to grow with curious and concerned residents.

“The challenge of social justice: to evoke a sense of community that we need to make our nation a better place, just as we make it a safer place.” — Marian Wright Edelman

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

Crowds started to gather on West Florissant, the major street intersecting Canfield Drive.

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

Crowds were always on Canfield Drive—everyone wanted to see the memorial. They all greeted one another. Residents of the apartment complex stood from their porches and balconies, nodding or smiling to passersby. St. Louis summers are humid though, and it seemed that the events taking place made the air even thicker.

As we headed back to West Florissant, I approached a woman as she exited her SUV. She lives in a house about half a block from the memorial site. She was tired; she had children who hadn’t been sleeping—scared from the aftermath of the killing, scared from the noise of the protestors and police. “People just keep coming,” she said.

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

The QuikTrip on West Florissant was burned down during the second night of protest. During the day, people drove to Ferguson to protest. At night, when they tried to leave, police officers barricaded the borders of the county, forcing them to stay inside their cars and/or barricading them inside parking lots. People started to leave their cars and were physically restrained from leaving the county. After a while, people started to retreat and some opted to break into stores.

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

QuikTrip became the hub for the community and the media. Community members brought food to feed thousands. Major news networks set up large white tents on the grass and parked their vans just a few yards away. Many protestors happily shared their stories to some reporters, while shunning others.

At QuikTrip, each gas pump portrayed a message dedicated to Mike Brown. In a sense, each pump was reserved: there was one dedicated for prayer, one for a banner displaying the names of unarmed people of color killed by the police, and one that served as the meeting place for people connecting to the movement on the ground from social media.

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

Photo by Mary Glen Fredrick 8/12/2014

Photo by Derecka Purnell 8/11/2014

At night, people in the community brought instruments, microphones, radios, and even danced on pieces of cardboard to celebrate and commemorate Mike Brown’s life.

“I didn’t break the rules, but I challenged the rules.” — Ella Baker, 1977

Photo by Mary Glen Fredrick 8/11/2014

Protesters lined West Florissant for about a mile. Parents brought their infants. The elderly brought lawn chairs. Bloods and Crips held hands in solidarity, along with people of all faiths. Cars played all types of music—NWA, Kirk Franklin, Lil’ Boosie. The crowd would often chant “Mike Brown” over blowing horns that rang amidst slow traffic.

“Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”— Fannie Lou Hamer

Photo by Mary Glen Fredrick 8/12/2014

Respectability politics will not save Black people. Personally, I think that people who promote this idea try to reconcile all of their positive experiences with all of the negative stereotypes following them. It does not matter whether someone is a college graduate, has a criminal record, and/or is a preacher: a police officer does not have the right to stereotype, agitate, and then kill an unarmed person with impunity. Rights are not attached to clothing, degrees, or race. Rights are attached to human beings.

Photo by Mary Glen Fredrick 8/12/2014