BY SEBASTIAN LANGER

Angela Merkel’s conservative Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) announced it’s 2017 election budget: 20 million Euro (around $22.1 million) on October 21. This is not the full sum needed for the campaign—every district’s candidate has to raise another 6,000 to 10,000 Euro for his or her personal campaigning. But that’s all. Really. Such figures are typical for Germany—Merkel’s major opponent’s budget was 23 million Euro in 2013.

Being in the United States during this election and having become accustomed to higher numbers, I had to smile when I saw Merkel’s budget. The role of money is probably one of the biggest and most astonishing differences between our two electoral systems.

This election, Hillary Clinton has spent an estimated $498 million on her campaign—almost 23 times what Merkel will spend—while Donald Trump has spent $248 million. Due to the limited campaign budget in Germany, our election campaigns are smaller and less professional. The most important parts are posters, mailings, and street campaigning (Straßenwahlkampf). TV-adds are regulated and limited—only parties are allowed to run them, not candidates. They are not expensive, either—public broadcasters have to air them for free, private broadcasters may only sell them at cost. Campaign posters have to be hung at street lights and nowhere else.

Social Democrats used the U.S. tradition of door-to-door campaigning for the first time in 2013, but the use of data collection has not been established. We have strong data protection laws, and after two dictatorships most citizens do not like the idea of their voting behavior being tracked.

The level of polarization in U.S. politics is another aspect that astonishes me. The most obvious explanation for less polarization in Germany might be our electoral system. We have a two-tier system with a total of 598 seats in Parliament—split evenly between 299 first-pass-the-post districts and representative state lists for another 299 seats. Most candidates on the state lists also run in a district, but that is not necessary. The result from this mixed electoral process is a high likeliness of meeting your district’s opponent again in Parliament. Maybe in the same committee. Or even in a coalition—all eight of the chancellors since the Second World War have needed a coalition partner to get elected in Parliament. Simply knowing this possible outcome may reduce a candidate’s willingness to start a smear campaign.

Another key difference in Germany is that we don’t have voter registration. In the U.S., each state has different laws about how to register to vote, but in Germany, every person who is eligible to vote receives a voting card at his registered address a few months before an election. This voting card includes your name and address and allows you (in combination with an ID card—which every German citizen has—or a driving license or passport) to enter the ballot box on election day. It also contains a box which can be checked to demand an absentee ballot. If the box is checked and the voting card is placed in any mailbox, the absentee ballot will be sent out as soon as it is printed. No justification is needed.

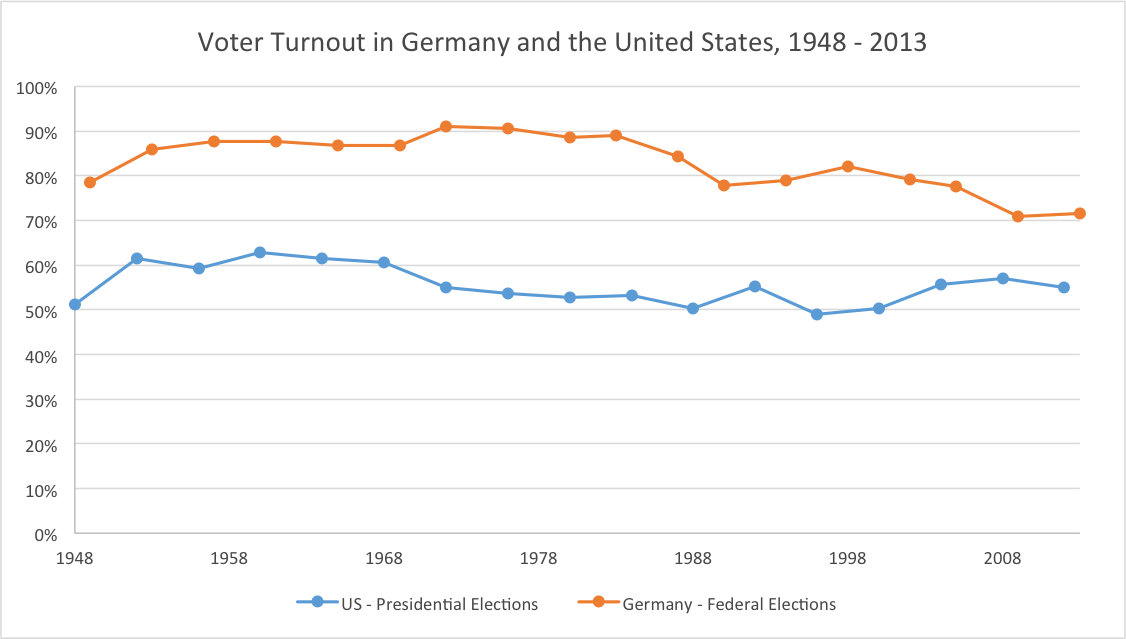

This relative ease of voting is a one possible reason for a higher voter turnout. Another reason might be the vote for the state list—no matter how safe your district is for a party, your vote for the state list will influence the Parliament. As the graph below shows, voting rates in Germany have remained, on average, 27.5 percentage points higher than the U.S. over the past 65 years.

Source: Wikipedia, Parliament files, and opensecrets.org.

Since there is no voter registration, each voter’s party affiliation is unknown. To become a member of a party, you have to join actively and donate a monthly contribution based on your income (for example, the contribution is 2.50 Euro for the unemployed, 5 Euro for students, and 45 Euro for fulltime employees with a monthly income of 4,000 Euro). Then you can participate at meetings and vote for party decisions. Parties can exclude their members if they do not donate or act against the well-being of the party (running on another ticket, campaigning for another party). Members vote for delegates who then decide who is running in the district and who gets which spot on the state lists.

Another significant difference is the role of the party in the political process. My impression of U.S. politics is that the party is a broad framework in which politicians act independently, or rely on a broader coalition than politicians in a multi-party system. In East Germany from 1949 to 1990, the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (GDR) had the party song “The Party is always right.” The GDR might be history, but some of this mentality persists. The party decides who is allowed to run in the districts and the rankings of candidates on the state lists. It pays for most of the campaign expenses, and in all parliaments voting is along party lines. Members of Parliament are theoretically free to vote their will, but in practice the parliamentary group decides with a majority how each member will vote. The leadership wields immense control over how its legislators operate.

The German system has its flaws, like easy access into Parliament and the availability of government funding for all parties regardless of their political platform. But after seeing the money, polarization, and obstacles to voting and how they influence campaigns and elections, I appreciate the German system more than ever before.

Sebastian studied medicine in Berlin, Toulouse and Jerusalem. He joined the Social Democratic Party in Germany during the 2006 election campaign in his state Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. He participated in the 2009 and 2013 federal campaigns as a student assistant to the party head quarters. During his year in France, he joined the Mouvement des Jeunes Socialistes and campaigned for François Hollande.

Cover Photo Credit: Penn State via Flickr.